I read many photographer’s bios that pinpoint the beginning of their photography career with the discovery or gift of a film camera. As photographers, we view our cameras as extensions of ourselves, becoming attached to their quirks and idiosyncrasies. But sometimes they are traded in for newer models, and for many, replaced with digital technology. We feel bad if we are unable to find a suitable home for them, but the market for film cameras has shrunk dramatically over the years. And yet, in Staunton, Virginia, a small town in the Shenandoah Valley, David Schwartz has created a safe-haven for our beloved cameras. The Camera Heritage Museum, a private collection of over 2,000 cameras that spans the history of photography, is open to the public and is accepting donations.

David Schwartz with his collection.

While Staunton may seem like an odd choice for the museum’s location, it plays an important role in photo history. The first photographer in the region began practicing photography in 1851, a mere 13 years after it’s invention in Paris. Many notable photographers including O. Winston Link, Michael Miley, Bernie Boston, and several White House photographers have lived and worked in Staunton. Schwartz, who owns a film development and printing business, began collecting cameras over 40 years ago. When the collection outgrew his home, Schwartz dedicated a portion of his storefront to its display.

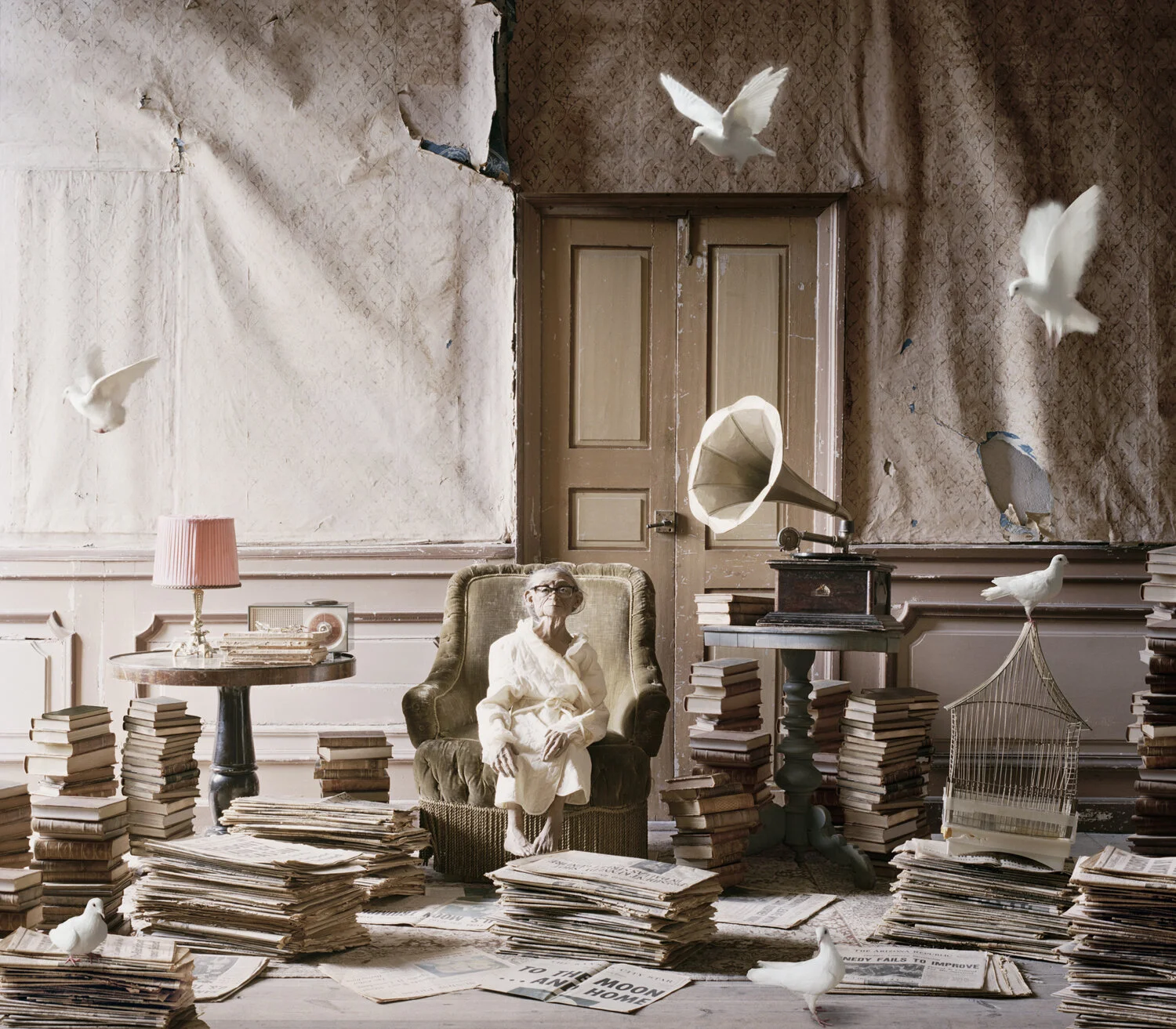

An 8x10 view camera stands at the museum’s entrance. Visitors walking past it can look through the ground glass to see the quaint downtown street outside projected upside-down and backwards. For many, this is their first time experiencing a view camera, and David Schwartz is readily available to greet them with an explanation and introduction to the collection.

And what a collection it is! Schwartz estimates that 95% of the cameras are fully functional and could happily be put to use if proper films were still available. The shelves contain cameras by the region’s notable photographers, as well as spy cameras, WWII cameras (including the "official" Pearl Harbor camera), bellows cameras, and—my personal favorite—a 19th century instant tintype camera which consists of a self-contained chemical bath for small, portable photographs.

Though relegated to a cramped display cases, Schwartz hopes that through its non-profit status and board of directors, the museum will in time have its own dedicated space. He envisions a by-donation museum with ample room to display not only the cameras, but also his wonderful collection of photographs made with them. These prints include O. Winston Link’s most famous works, anonymous daguerreotypes, and prints and plates by Michael Miley. Each display would contain descriptive text and the entire collection would be published in a catalogue. While Schwartz is extremely knowledgeable about the history of photography, he is a busy man. During my visit there were another eight visitors and five phone calls from people wanting to donate cameras. With funding, the museum would be able to provide accompanying texts for visitors to guide and educate themselves.

Schwartz sees his role in the photography community shifting from photographer and printer to curator and historian. He feels that now more than ever it is important to chronicle and preserve photography’s evolution. With reviving interest of historic process and our society’s current obsession with all things vintage, the museum stands a good chance of engaging new audiences. During my visit I observed the older visitors become nostalgic when looking at the Kodak Brownies and other common family cameras from their youth, while younger visitors, sometimes unfamiliar with life before camera phones, are fascinated to learn how cameras work at their most basic level. By the time they leave and walk past the 8x10 on their way out the door, they have a completely new understanding of what a photograph is.

Cameras were invented to preserve time through photographs, so it is fitting that there should be a museum dedicated to their history and preservation. Whether you are a photographer, a photo enthusiast, or just looking to kill a couple of hours in downtown Staunton, I encourage you to visit this treasure. The collection includes cameras from all over the world brought together in one small town.

Kat Kiernan is the Editor-in-Cheif of Don't Take Pictures and the Owner and Director of The Kiernan Gallery.