Ishiuchi Miyako (photo by the author)

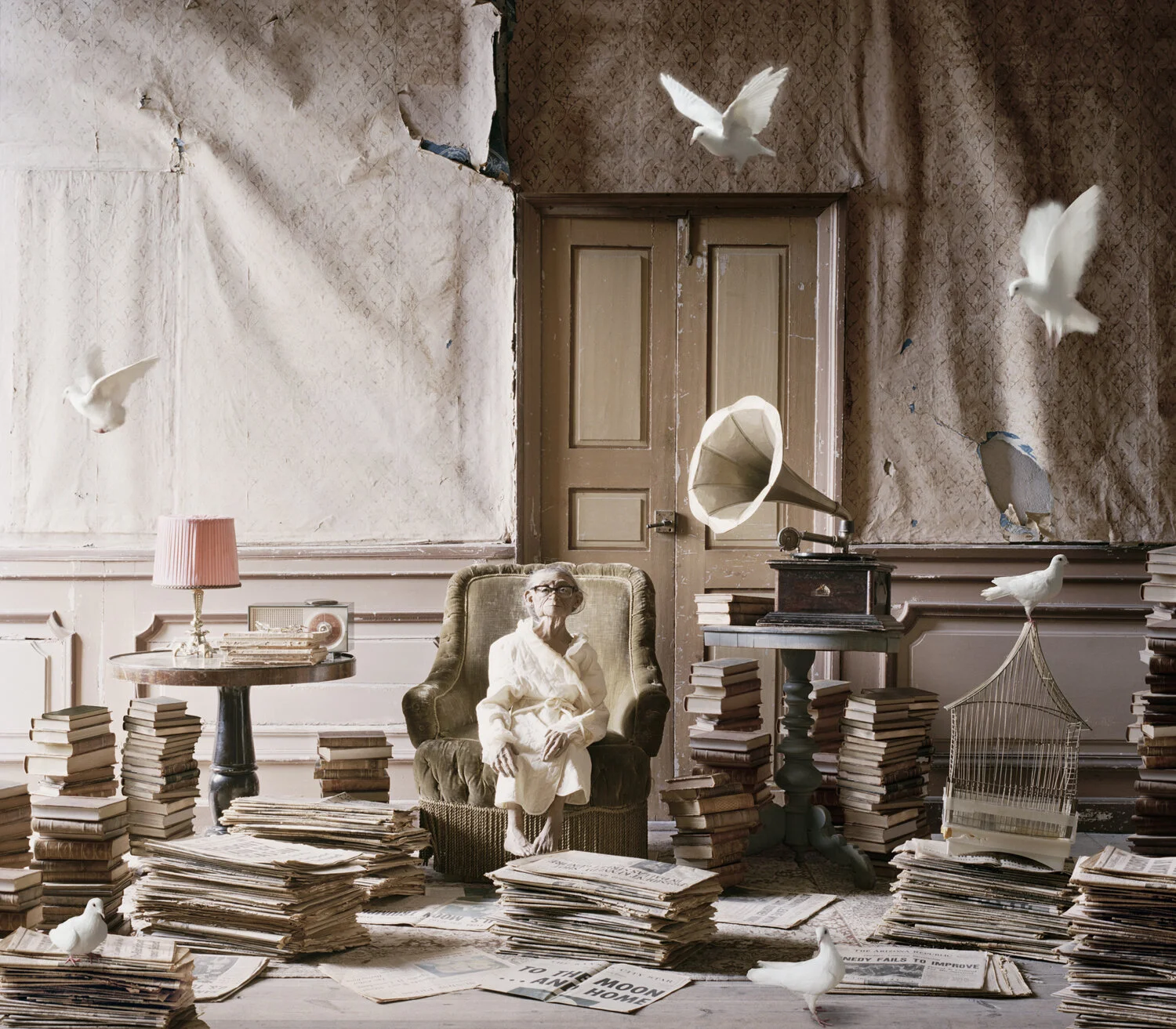

Armory week means long days punctuated by moments of sublimity. This year, The Armory Show itself did not have the range and depth of photography as some recent previous shows, and while it’s probably impossible to overstate the impact of the show generally, this year’s thinner-than-usual photography exhibitions meant that many of the best surprises were in other media. Nonetheless, there were standouts. Idris Khan’s platinum prints at Alan Cristea Gallery surprised with their tones and aesthetic, their blending of images so extensively busied that they become almost mystical. Michael Hoppen Gallery exhibited a compelling range of artists, with Horacio Coppola’s and Kati Horna’s alluring vintage prints immediately drawing the eye. Coppola’s, in particular, seemed to glow with life and seemed decidedly contemporary despite having been made 80 years ago. Alan Cristea also exhibited Ishiuchi Miyako. Miyako’s color still lifes have the feel of pop art, yet the simplicity of them is complicated by his careful arrangement. The objects of the images creep toward the edges, suggesting something like discovery of found objects more than staged scene. The result is a subtle engagement with the objects that surprised me and made me go back to see them a second time. Howard Greenberg Gallery offered up some of the strongest images of the entire show—regardless of media. Jungin Lee’s landscapes were juxtaposed on a facing wall with the subdued, but clear and carefully delineated still lifes of Joel Meyerowitz. Alex Majoli’s highly charged and large scale figural images were powerful, and the pain evinced in some of them was palpable and distressing. The rushing, crying crowd of children in one of the images is impossible to get out of your mind once you’ve seen it, and how the folks at Greenberg were able to pull off a booth with such emotional imagery alongside the quiet work of Lee or Meyerowitz is testament to their careful, if surprising, curation.

Alex Majoli (photo by the author)

Joel Meyerowitz (photo by the author)

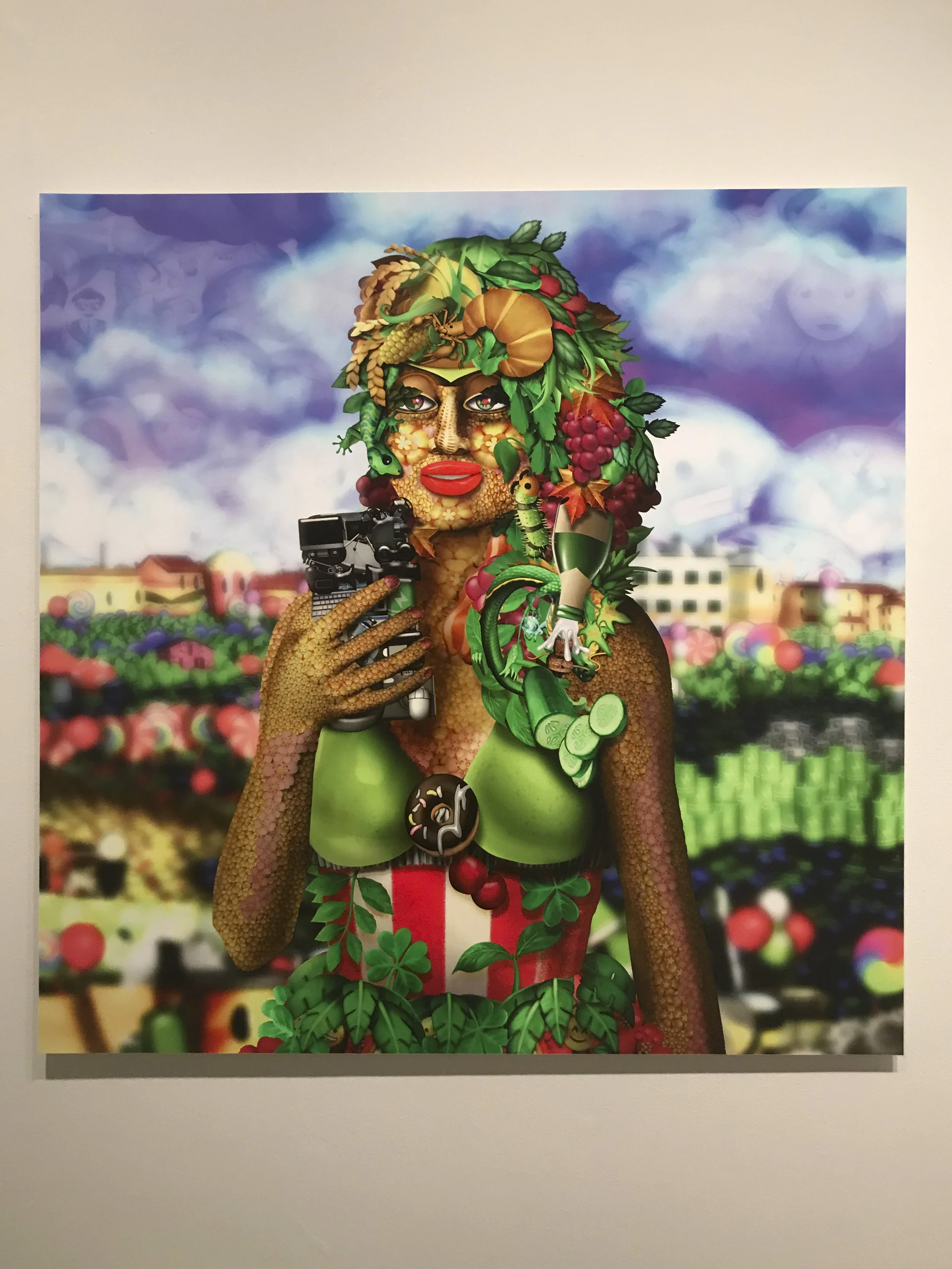

There were others throughout the show worth seeing, but again, they were scattered and, it seemed to me, harder to find than previous years. James Casebere’s strange and painterly images were at both Lisson Gallery and Sean Kelly, and Lia Rumma Gallery had a range of interesting images, with Ugo Mulas’ and Thomas Ruff’s work as standouts. John Wood’s photo-collages of guns were worth a close look at Bruce Silverstein, who should be acknowledged for the timely resurrection of this work. It, too, was surprisingly contemporary, both in how the works were made and in the topic of the imagery. Ben Cauchi’s images at Ingleby Gallery reminded me of the intense rumination on form that emerges when artists capture monolithic structures with their process. The use of ambrotype for the process not only made sense, but seems almost necessary given the impact of the work. And Clarissa Tossin’s images of homes, remade by the imposing arm of an onlooker and participant, kept me thinking—and indeed still does. I’m still not sure why I like these images, but I suspect it has something to do with our cultural fascination with home make-overs, our current obsession with place, and the power of remaking the domestic. Regardless, the images of stuck with me, and perhaps Sicardi Gallery probably would have a strong opinion why.

Clarissa Tossin (photo by the author)

Throughout Armory, though, only one image truly took my breath away. It was the expansive landscape by Stan Douglas at Victoria Miro’s booth. The print, mounted on aluminum, was dark and brooding, but beautiful. The depth of blacks are hard to describe, and it’s impossible for me to imagine how he was able to make them (and impossible for me to document it for this review), but the result is a stunning, eight and a half foot wide image that stretched across the wall and invited you into a dark, but magical, landscape of cabins, water, and, surprisingly, industry. I quite literally gasped when I saw the image, and I found myself wanting to touch it—not to feel it, but to somehow be absorbed into it. Douglas manages to make the dark inviting, even if not entirely safe. I still find myself wanting to go to that world, wherever it may be.

Roger Thompson is the Senior Editor for Don’t Take Pictures. His critical writings have appeared in exhibition catalogues and he has written extensively on self-taught artists with features in Raw Vision and The Outsider. He currently resides in Long Island, New York and is a Professor at Stony Brook University.