Journeys have inspired writers and photographers for as long as storytelling has been recorded—and certainly even before then. The idea of a grand adventure evokes a sense of romance, of placing oneself into a unique, or strange environment. We feel nostalgic or melancholic or even envious of the road less traveled, and, as evidenced by the wealth of journey-based photography projects, we are hungry for them, too.

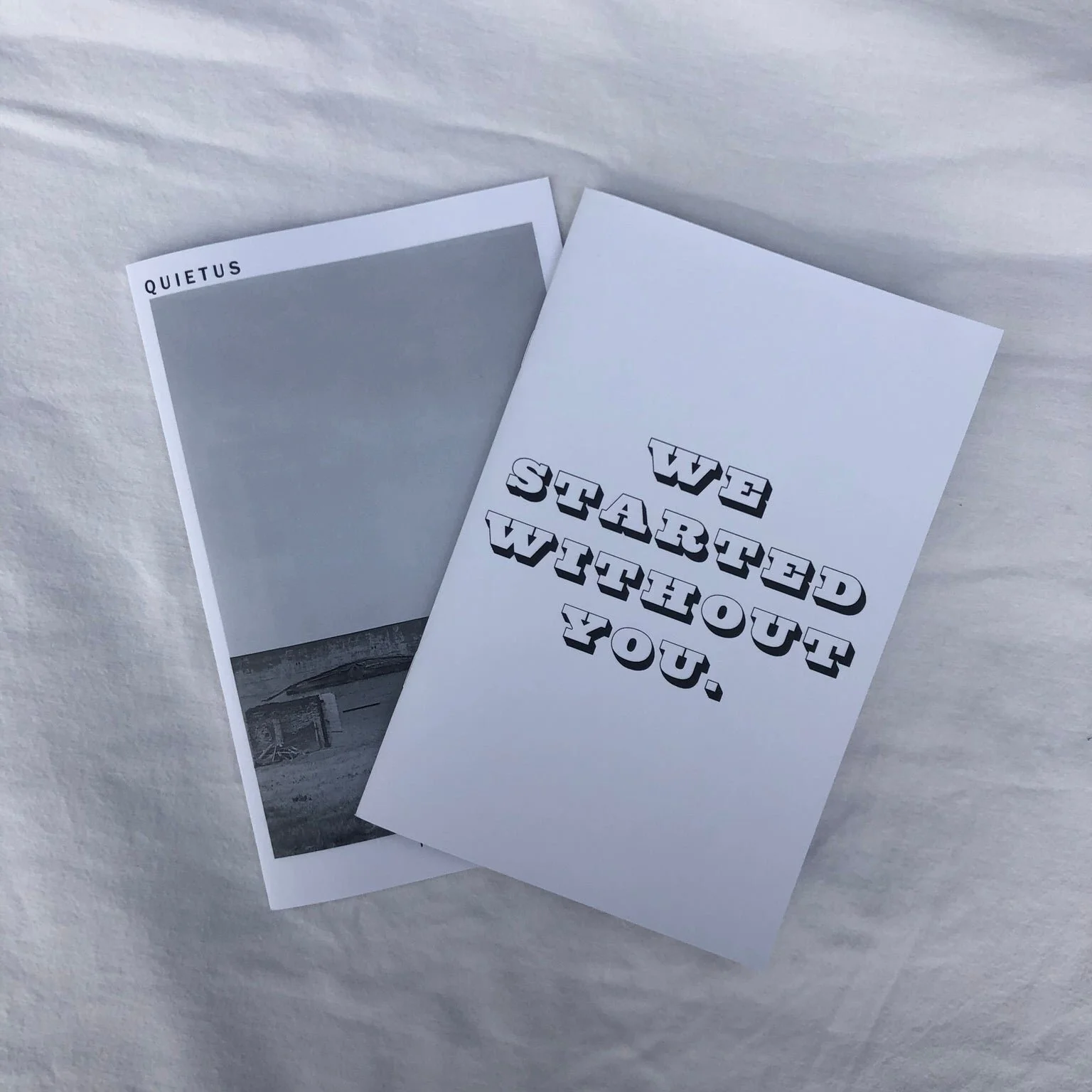

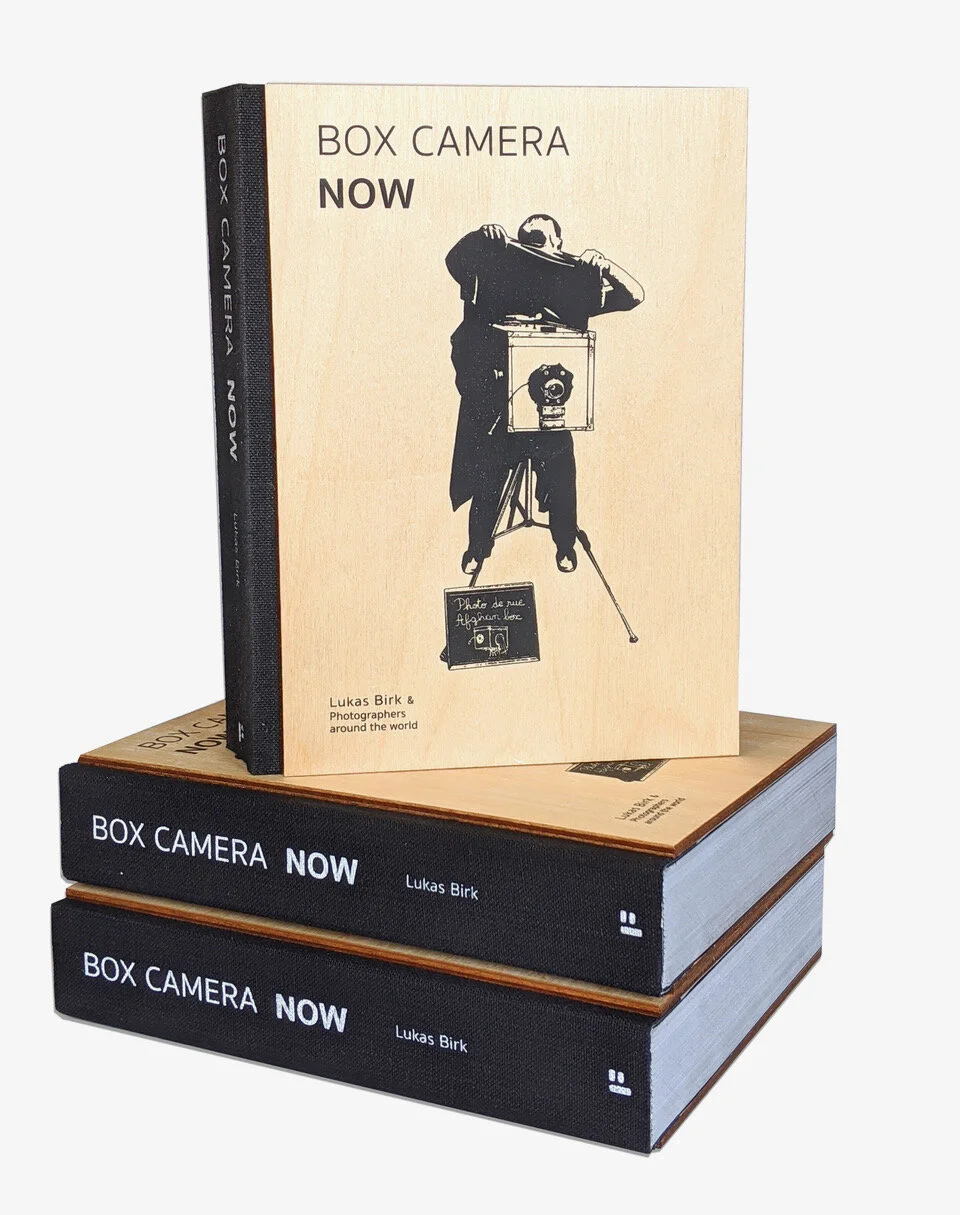

In 2017, German photographer Tamina-Florentine Zuch placed herself into a foreign environment—the United States—where she spent six weeks riding the rails from coast to coast, embedded in America’s hobo youth subculture. She documented those she encountered on the journey, some of whom she traveled with for a period of only a few hours. Others, for weeks. Her writings and photographs of the experience were published as a book in 2018 by German Riva titled Supertramp.

Zuch’s work is rich with images that reflect the human condition. She is a sensitive photographer whose trust with her subjects is evident when viewing her work. The viewer instantly feels a connection to her fellow travelers. They are familiar to us, but mostly as background against the worlds in which we live; recognizable, but not known. Zuch brings these people—sometimes called hobos—into the forefront and presents them without prejudice. But where other photographers have approached America’s subcultures as quiet observers, Zuch is an active participant, including herself in the work and writing eloquently in Supertramp about her experiences.

There is a warmth to her photographs, and although there are plenty of images that speak to the motion of the trains, her work often presents a sense of stillness, of time passing slowly or not at all. The travelers sit, their feet dangling off the freight cars as the train rumbles along. We find them nestled atop a rock enjoying a seemingly private lagoon or sitting at a table, illuminated by a single lantern. These images give the viewer pause, to also feel reflective when engaging with these photographs. What we see is a sense of freedom.

Zuch brings us into intimate spaces with the people she meets and takes us through their daily routines. At times this feels nomadic, and other times like simply a glimpse of their day-to-day lives. The atmosphere here doesn’t feel forced or contrived; it feels authentic.

Crossing America and documenting its quirks, charms, and subcultures has captivated photographers including Robert Frank, Stephen Shore, Diane Arbus, and others who have collectively documented many—but hardly all—of America’s unique societies. Zuch photographs her own journey across the United States and where it converges with other train-hopping and hitchhiking adventurers.

Wherever we live, we wonder how our culture resonates with someone who doesn’t live there. Before her journey, Zuch wasn’t very interested in America, calling it “without culture” in an interview with NEON. But that changed quickly as she was affected deeply by the openness she discovered from the people she met along her journey. Still, she elicits a sense of worry in the viewer as we learn of her hitchhiking, meeting former inmates, or simply taking the risk of riding the trains. We question how she dealt with the unknown, of traveling solo in highly vulnerable environments.

The work in Supertramp feels like something only someone in their youth would undertake. It requires a flexible time frame and frankly, a far less concrete idea of danger. Nonetheless, Zuch’s passion is evident, notably in one remarkable image in which she rides atop the train, her smile as wide as the train cars are long, set against a bucolic scene and a snow-capped mountain. It looks like the definition of exhilaration. Train travel is romantic precisely because of its inherent paradox: the stability of the steel tracks rooted firmly within the land afford an opportunity for its passengers to find release as the freight cars rumble on, to enter new geographies, new relationships, new adventures.

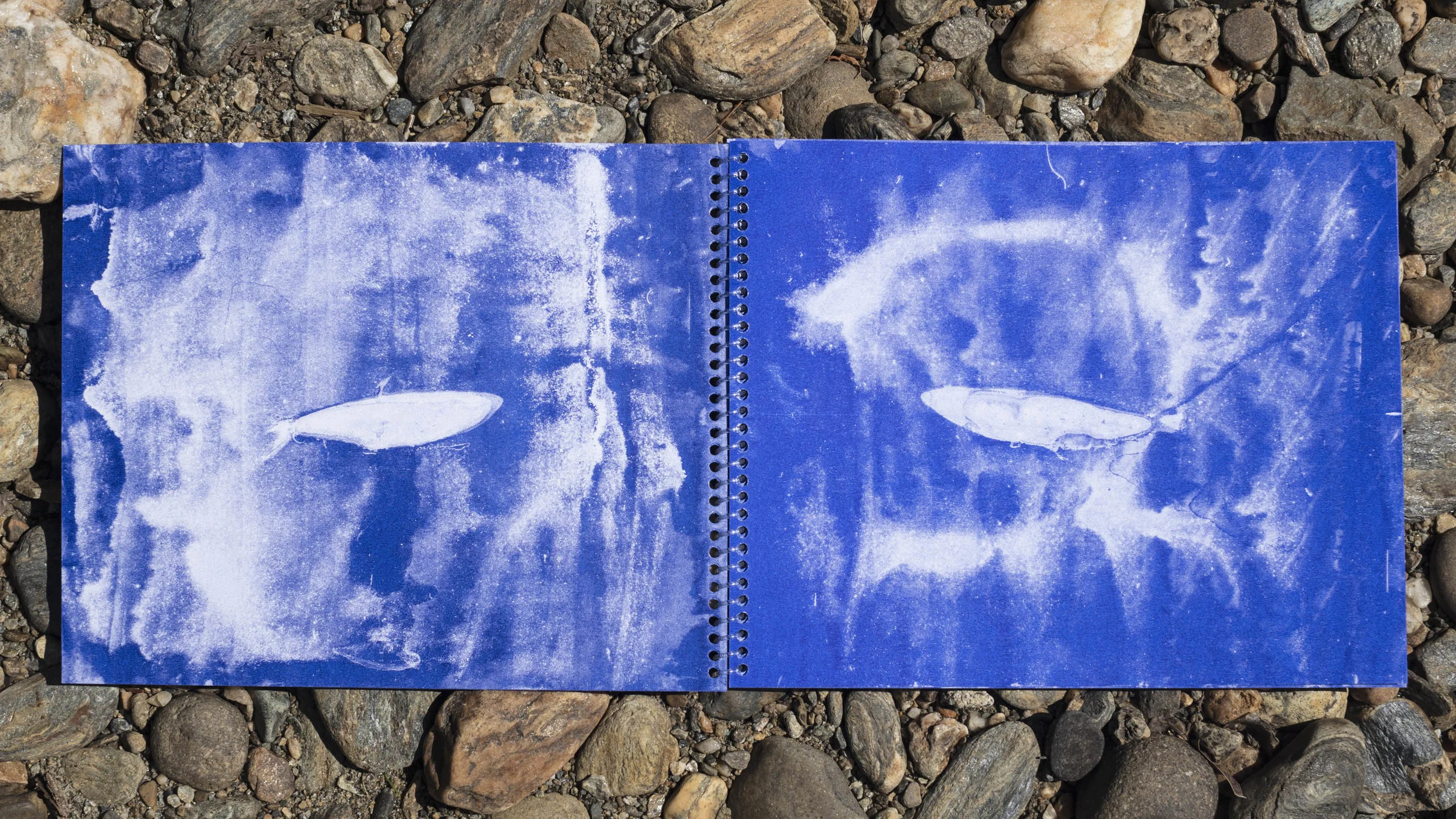

There is a timeless quality to Zuch’s photographs. Although she is a documentarian, when looking at her work, it’s easy to imagine her as a friend. She is the explorer you wait at home for, eager to learn of her travels and adventures, look at her maps, handle her trinkets collected along her journey, and to listen as she reads from her journal, telling the stories of life on the road. In that sense, Supertramp feels like a scrapbook, a collection of memories and short stories; vignettes of lives known and cities visited. It’s a look into a sensitive soul who stepped out of her world and connected with a new one that covered 6,000 miles.

This article first appeared in Issue 14, The Explorers Issue