Lincoln, Nebraska, gained 50 new patrons of the arts this summer. So did Fargo, North Dakota. In Philadelphia, there were 100. More than just purchasing museum memberships, these people were participating in one of the fastest growing movements in art collecting: Community Supported Art.

Often referred to by its abbreviation, community supported art is a movement that connects artists to a local buying audience. Modeled after the community supported agriculture—the original C.S.A.’s—these programs sell a limited number of “shares” to members of the community, who then receive “harvests” periodically during the mid-summer and early fall months that generally comprise the C.S.A. season. Rather than receiving farm fresh tomatoes and carrots, community supported art provides its members with small artworks made for the occasion by local artists in a limited edition. The participating artists are chosen by a jury and employ a wide variety of media and styles. For artists who do not work in editions, such as painters and ceramicists, the C.S.A. programs generally require that they create a series of very similar works that function as an edition. A party is often held on these pick-up days, giving the members a chance to meet the people whose artistic careers they are supporting.

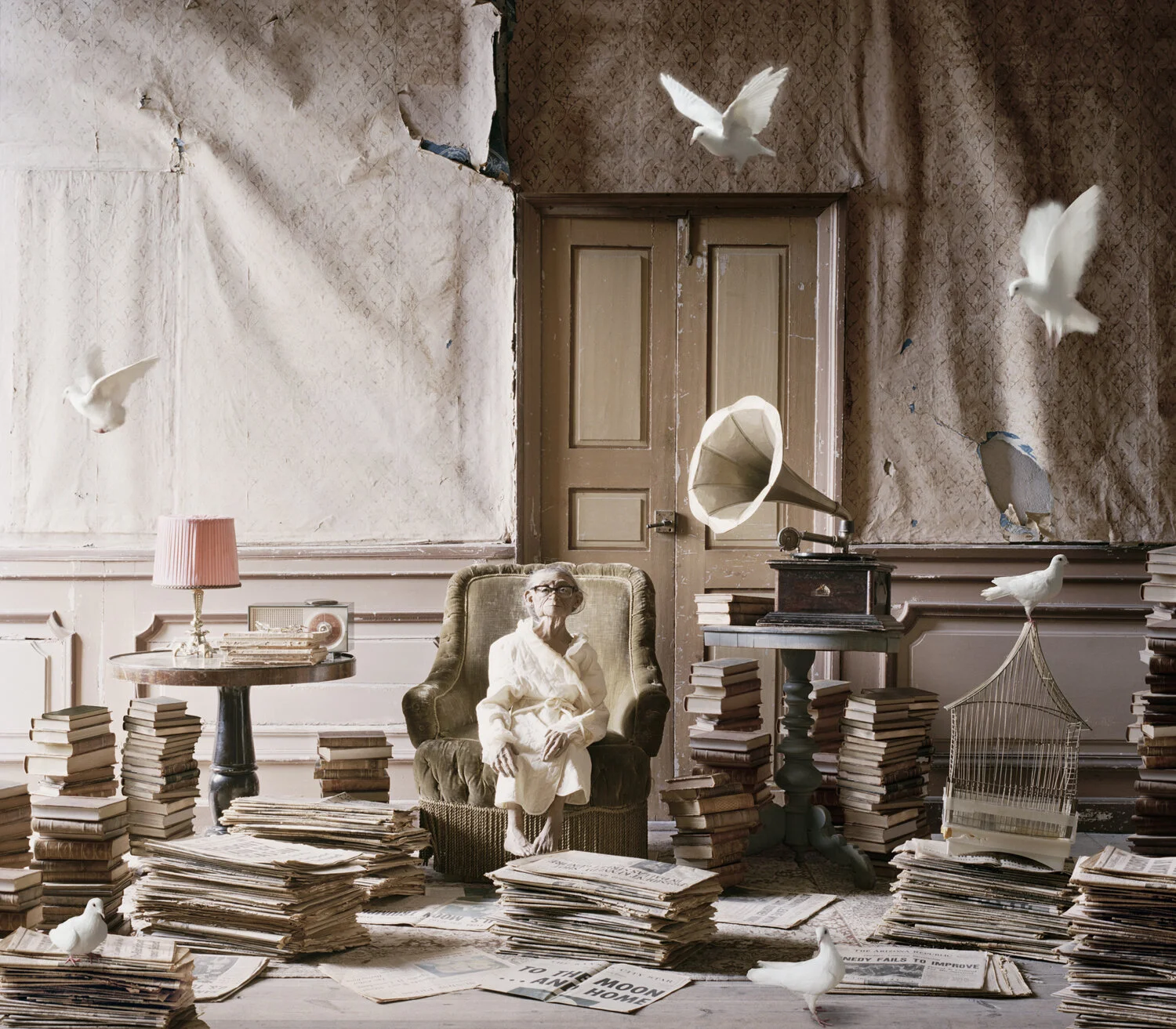

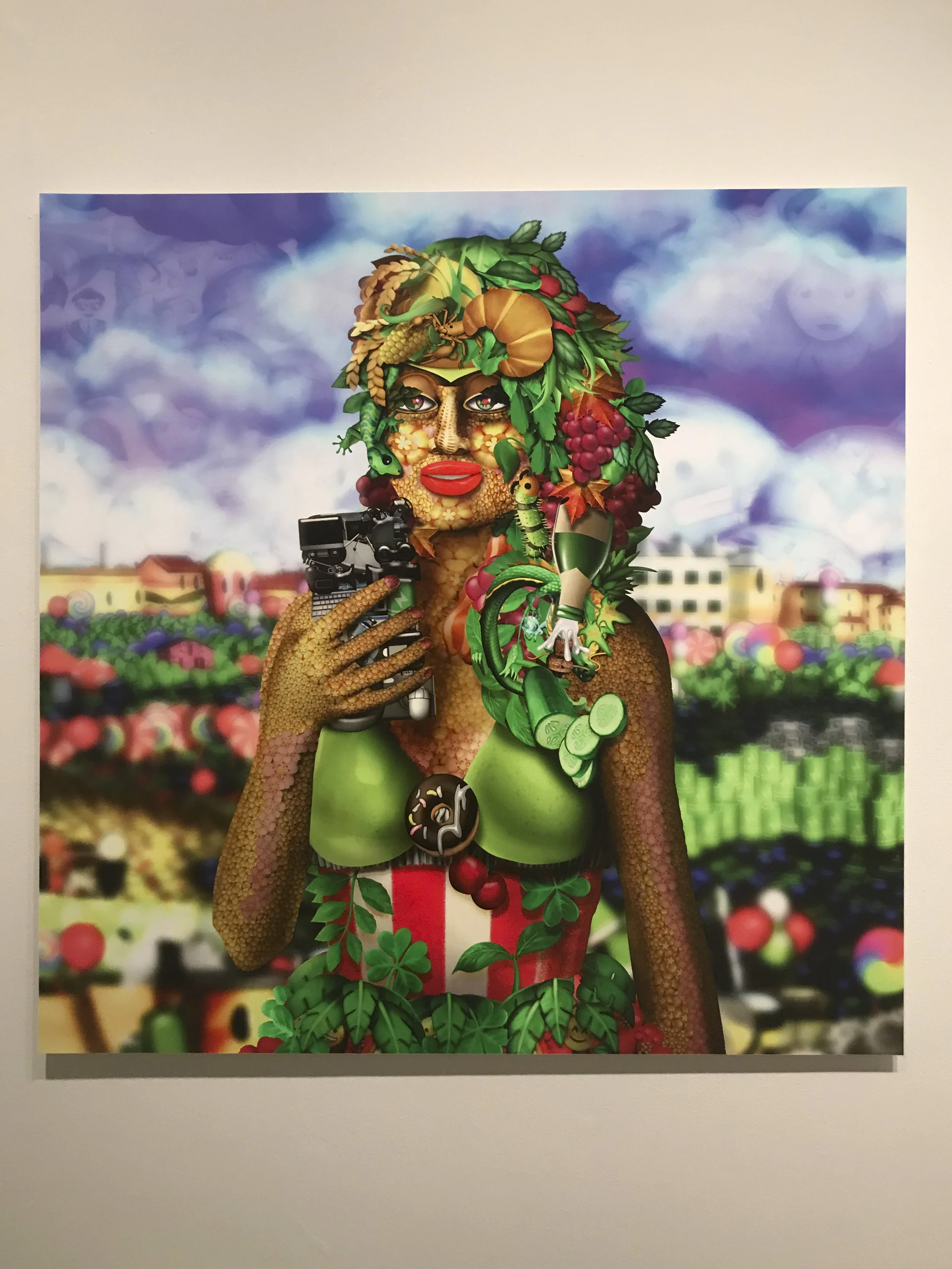

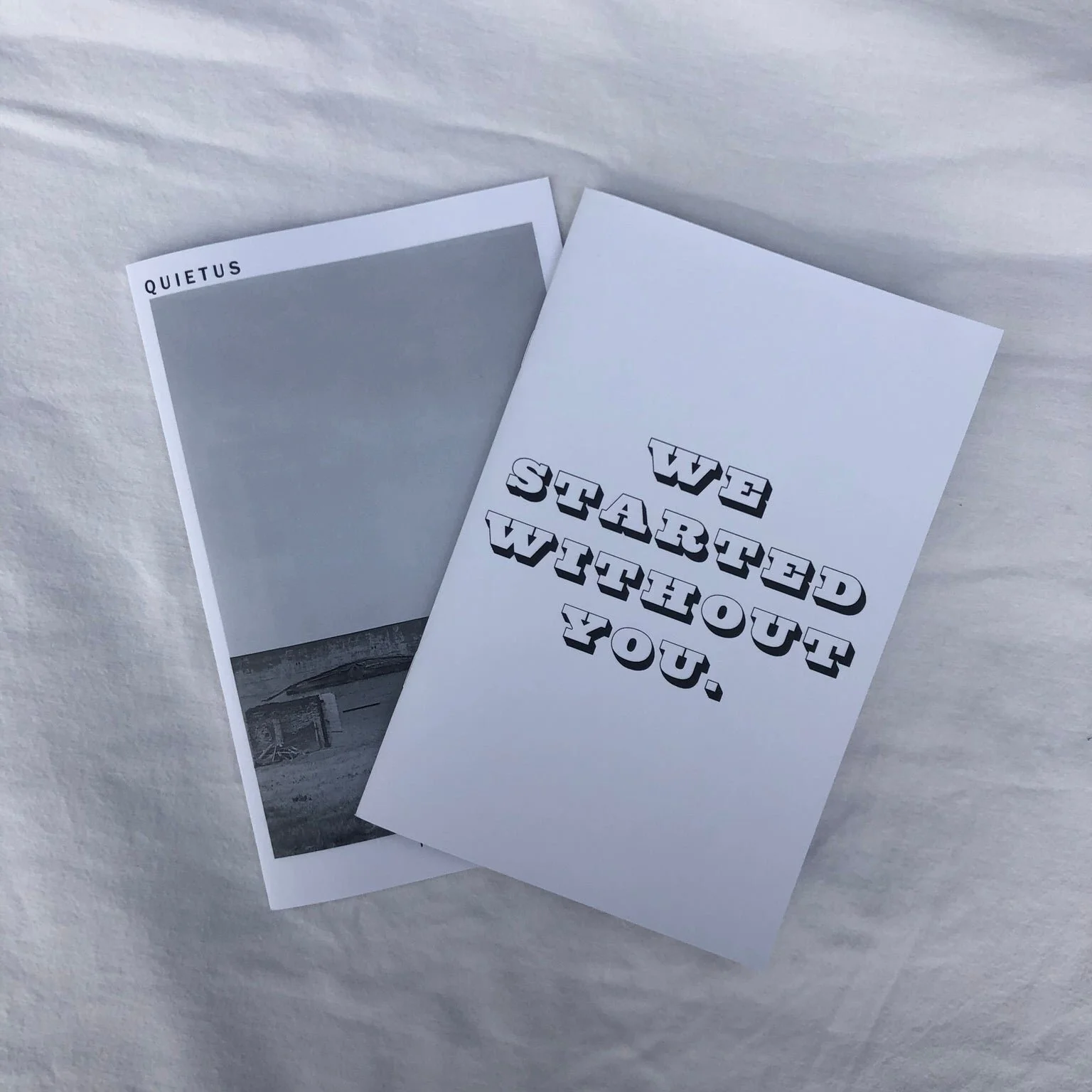

Springboard for the Arts CSA. Photo credit: Zoe Prinds-Flash

The first Community Supported Art program began in St. Paul, Minnesota, in 2010 as a joint project by Springboard for the Arts and MNArtists.org, with funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. The program was an instant success, and this new form of C.S.A. began to spring up all over the country. Now in its fifth year, the St. Paul program’s 50 shareholders will each receive work from all nine of this season’s artists. St. Paul’s C.S.A. program charges $350 for a share, and prices in other cities tend to vary between $300 and $400 for a season’s worth of art. Some charge more for the opportunity, such as Brooklyn’s CSA+D, which sells its 50 shares for $500 each.

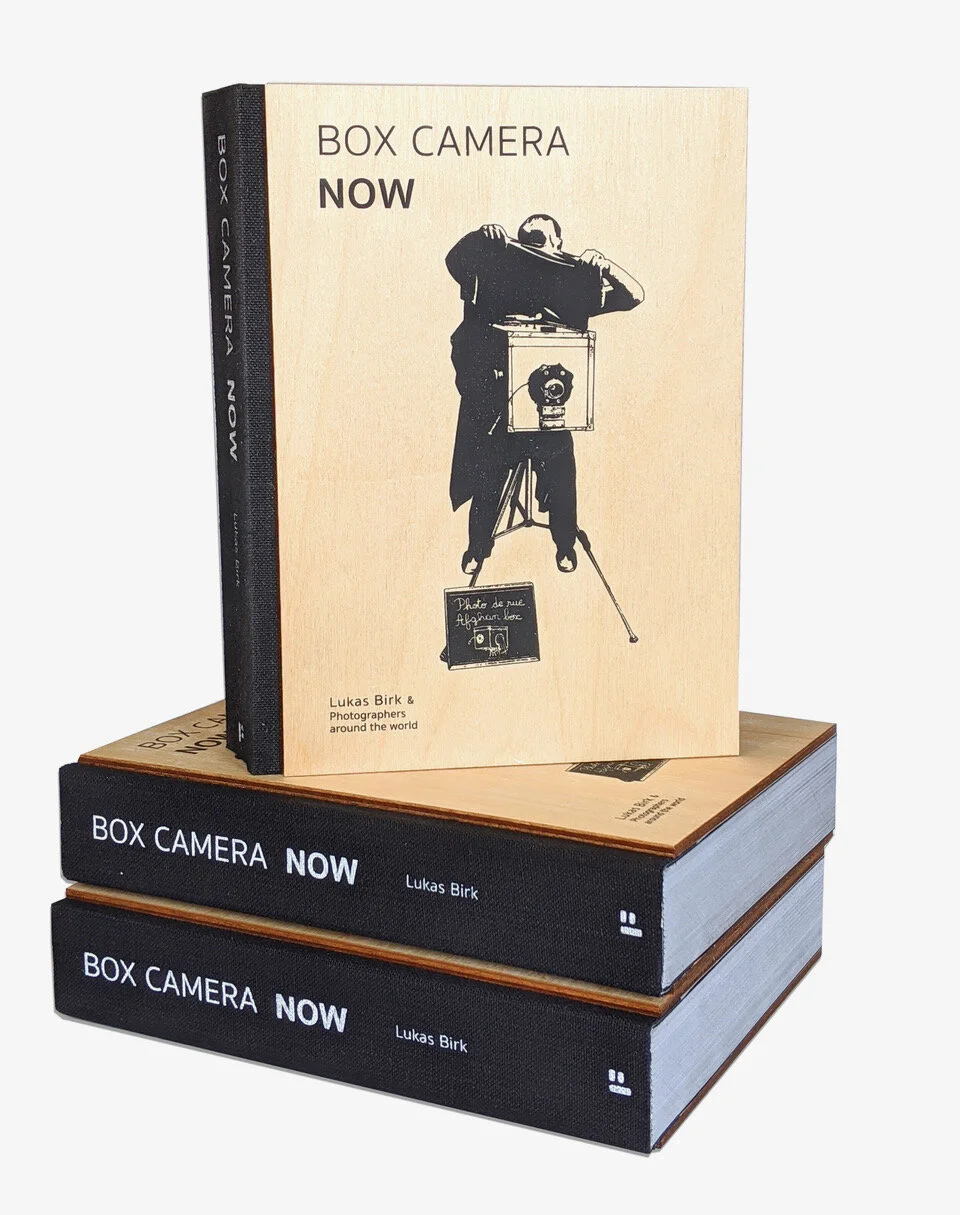

Photography is a natural fit for community supported art programs. Not only are works easily printed in editions, but photography is a medium that is comparatively easy to display and understand. Because most C.S.A.’s seek to ensure that shareholders receive a wide range of media however, photographers represent only a small minority of participating artists. An exception to this trend is the Crusade for Art’s C.S.A., which exclusively presents photographers and targets a collecting community rather than a geographic one. (Full disclosure: the Executive Director of Crusade for Art, Jennifer Schwartz, wrote an article that appeared in Issue 2.)

Springboard for the Arts CSA. Photo credit: Zoe Prinds-Flash

For artists, the benefit of participating in a community supported art program is clear: their work is essentially pre-sold to the C.S.A.’s shareholders, guaranteeing them between $1,000 and $1,500 in return for creating a new piece in an edition of 50. Perhaps more importantly, they connect with local arts patrons who are receptive to new artists and willing to put their money into their local art community. After discovering an artist through a C.S.A., a shareholder may want to collect more of that artist’s work. Such connections have the potential to create beneficial and long-lasting relationships. Equally important, participating in a community supported art program allows the artists themselves to connect with fellow artists in their area, adding to the vibrancy of their creative community.

For budding collectors, buying into a C.S.A. can serve as a means to begin a collection or to easily get a flavor of the local talent. However, these rationales do not lend themselves to repeat subscriptions. If the goal is to fill wall space and learn about a region’s art scene, then receiving six pieces a season will soon become overwhelming. Although rather few well-known artists have participated in C.S.A.’s to date, the low price of a share allows budget conscious collectors to get their hands on a small work by an artists they admire or acquire a piece by an up-and-coming artist before they “make it big.”

Springboard for the Arts CSA. Photo credit: Zoe Prinds-Flash

Established collectors are more likely motivated by the community and social benefits of C.S.A.’s rather than the art it will bring to their doorstep. Serious community art collectors do not need a C.S.A. to find local talent, especially considering that the participating artists are published online. Because shareholders do not know what artwork they will receive, they have limited insight into whether it will match their interest or style, or if it will be easy to display. An interested collector could approach specific artists directly, removing the limitations and the uncertainties associated with receiving an art “harvest.”

Perhaps most significantly, the manner in which Community Supported Art programs select and deliver art presents a model that is decidedly at odds with traditional collecting. Without the ability to select and evaluate art before taking it home, shareholders cede the curatorial aspects of acquiring art to the C.S.A.’s organizers, foregoing one of the most important parts of the collecting process. In seeking to appeal to as much of the public as possible, organizers generally try to present a broad spectrum of community artists and media. With 50 shareholders to please, a C.S.A. program may be inclined to select artists whose work is more decorative than deliberative. The result is that collectors are getting the art that is available rather than the art of their choosing. This might be good for filling wall space, but does little to hone a collector’s eye and vision.

Springboard for the Arts CSA. Photo credit: Zoe Prinds-Flash

To be sure, connecting with and supporting local artists is a good thing. Community Supported Art programs harness the collective buying power of their shareholders to pay local artists for new work. It also introduces the artists to a receptive audience, opening the door for a more direct collecting relationship. And if, after buying a share, you get art that you don’t care for or can’t display? Well, maybe you don’t keep it. After all, receiving even one piece that you are proud to own is well worth the price of a C.S.A. share. Discovering a new local artist that you love? That’s worth a lot more.

This article first appeared in Issue 3.

W.G. Beecher is an editor for Don’t Take Pictures and a budding art collector.