The following is Rachel Segal Hamilton’s introduction for Samuel Zeller’s monograph, Botanical.

Botanical by Samuel Zeller

Hoxton Mini Press, 2018

Hardcover

144pp., £16.95

Writing in 1914, the German poet Paul Scheerbart fantasied about doing away with bricks as a material for building and replacing them with ‘lustrous, colorful, mystical and noble glass walls’ to create nothing less than ‘a paradise on Earth.’ His words spring to mind when looking at Samuel Zeller’s Botanical series. Gazing through the glass walls of greenhouses at plants encased inside like precious jewels is a magical experience. With their interplay of delicate light, rough texture and lush colour, his shots offer a spellbinding visual pleasure. These greenhouses are contained, controlled perfect little worlds of their own, immune to the wind, the frost, the pests. But like Eden, these enclosed and manufactured spaces bristle with nature.

Greenhouses have existed in various guises since Roman times but it was in the 19th century that they really came into their own, with the construction of iconic glasshouses such as those at London’s Kew Gardens and the Royal Greenhouses of Laeken. Often they housed vast collections of tropical specimens, colonial spoils from overseas. The Conservatory and Botanical Garden of the city of Geneva, built in 1817, is where Botanical began—largely by accident. One sunny evening in March 2015, seeking a calming panacea to a stressful day at work, Samuel Zeller got off the train a stop early and wandered around, randomly shooting pictures of plants that caught his eye. It was only a week later, looking through the pictures on his computer, that he saw their potential. The project has since taken him to greenhouses in Belgium, Scotland, Poland, and France.

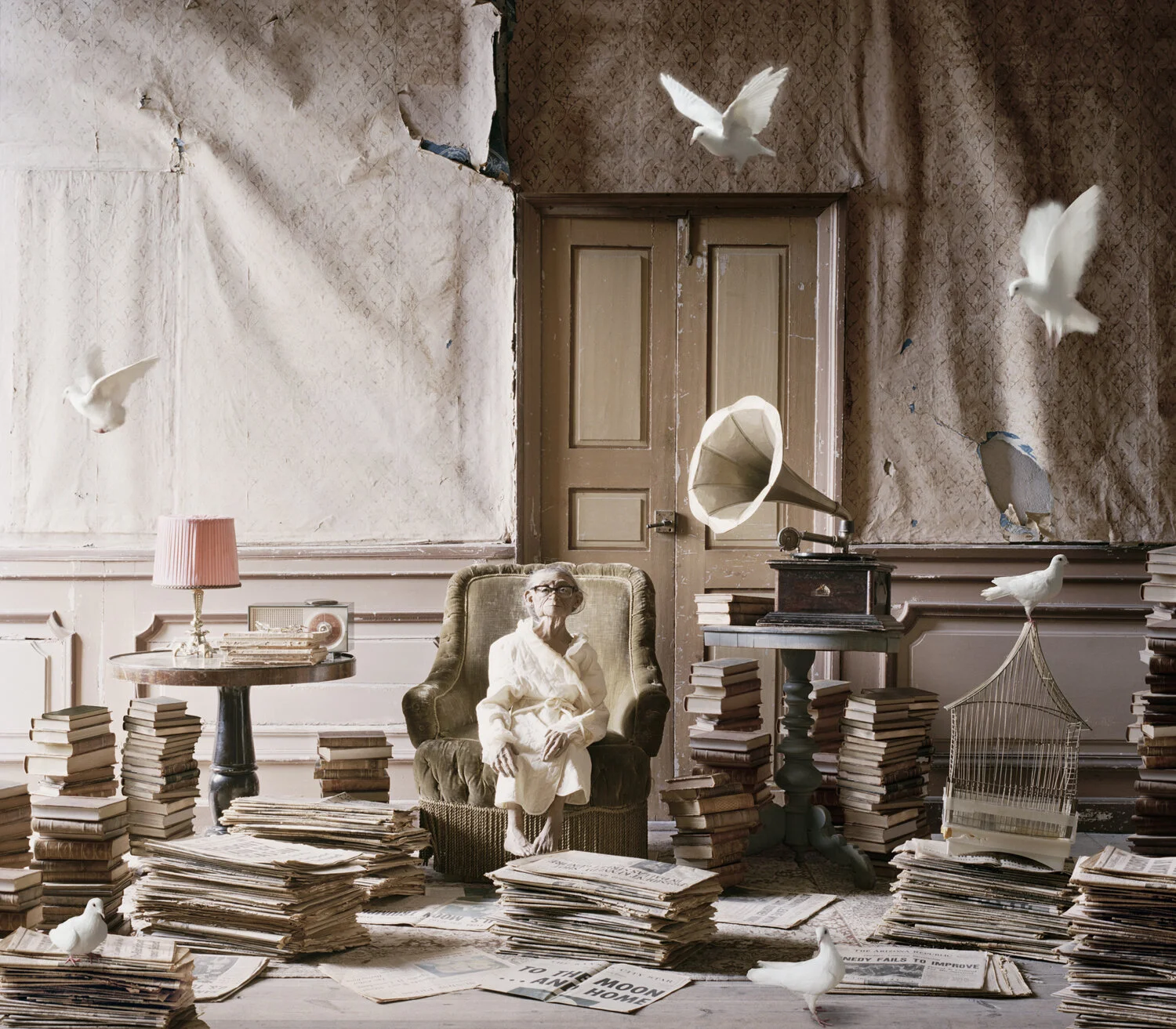

Untitled

Before choosing the next greenhouse to visit, Zeller researches online, scouting pictures to identify the precise texture of the glass he’ll find, whether the plants are located close to the glass. Each one is its own adventure but there is a consistency to his approach. Zeller is the son of artists and a painterly influence is clear. His shots have the smudgy energy of Impressionist works by Édouard Manet and Auguste Renoir, both of whom painted greenhouses. So too is a graphic designer’s eye, honed during his pre-photography career. His inclusion of the metal structure of the greenhouse creates a framing and flattening two-dimensional, canvas-like effect that plays with our sense of foreground and background. Clusters of leaves and flowers interrupt the deep blue, green-grey darkness in sudden streaks of pink, red or bright yellow. Rivulets of condensation form patterns on the glass, muck glistens golden in the sunlight.

Clerodendrum splendens Lamiaceae

And yet it would be a mistake to think of Botanical purely in terms of its aesthetics. There’s a deeper message behind the series. Like our 19th century forbears, we’re living through a period of rapid change, and facing an uncertain future. As seasons blur and weather conditions become more unpredictable, being able to control the climate in which we grow crops takes on a practical urgency. Across the world, people are exploring innovative ways to do that—living roofs, aquaponics systems, urban farms, greenhouse skyscrapers, even greenhouses in space…Scheerbert thought glass had the power to transform the world into a more beautiful, more ethical place. In Zeller’s work, we see the glasshouse as a thing of wonder, but also a symbol of hope—of human ingenuity working hand-in-hand with nature.

Rachel Segal Hamilton is writer and the author of Unseen London. She is a Contributing Editor for the Royal Photographic Society Journal and has written for VICE, The Telegraph, Sotheby’s Institute of Art, Hoxton Mini Press, and many other publications. Follow her on twitter @rachsh

Don’t Take Pictures issue 12