Smothered by duvets, decapitated by curtains, and dismembered by drywall; the women in Patty Carroll’s photographs meet their demise overwhelmed by an accumulation of domestic stuff. The colorful, saturated tableaus are as much a humorous critique on the suburban housewife as they are an absurdist eulogy to their overlooked narratives. Her photographs navigate the complicated relationship that develops at the intersection of traditional femininity and the American middle-class home. Anonymous Women: Domestic Demise is the winner of the inaugural Don’t Take Pictures Prize for Contemporary Photography.

Recently published as a monograph by Ain’t Bad, the project took shape when Carroll purchased a farmhouse built in the 1950s and began to obsessively decorate and furnish it as “the perfect 1950s home.” She noted that, as women, “We are attached to our home in ways that are not really definable. Whereas the home I created is both myth and reality, I think we all think of our homes as extensions of ourselves.”

Carroll’s work has been shaped in large part by her upbringing in suburban Chicago. “My anonymous woman and her home is based on suburban living, which is how I grew up.” It is hard not to look back on childhood homes and not have strong associations with certain objects. One often forgets that these objects were most likely chosen by a woman, as an extension of her identity, which has now become imprinted on us. The women who procure these objects participate in labors that go unnoticed or unappreciated. They run homes and raise children but disappear silently into the backdrop of domestic homelife. Yet these homemakers would also sometimes participate in a strange consumerist cortege; longing for a particular identity or class built on an artifice of acquired objects.

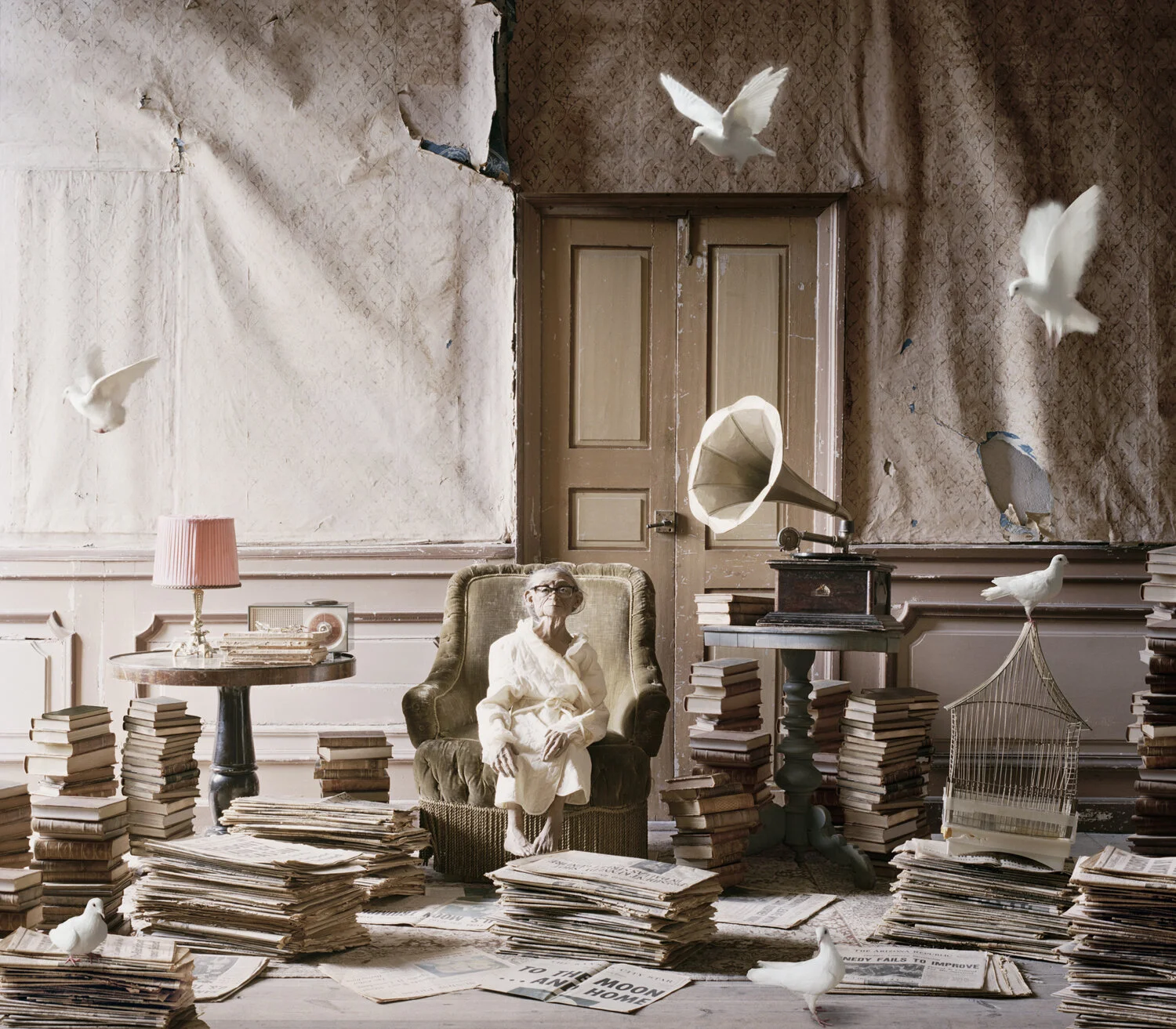

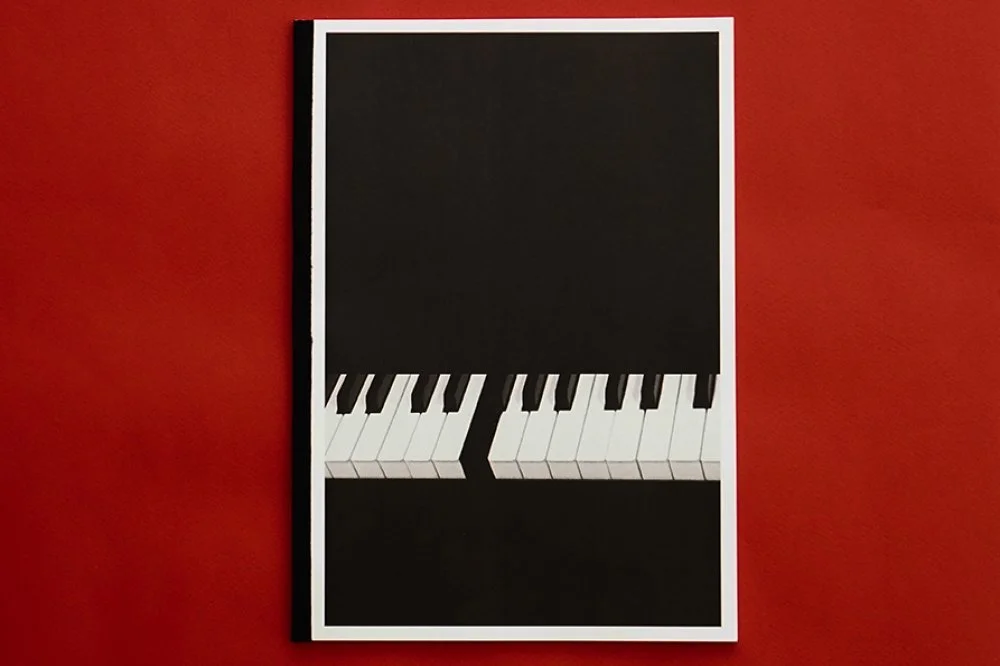

Pie-Eyed

The femme figures in Carroll’s work are both an agent to and victim of their own demise, motivated by consumer culture and pressured by conventional gender roles to curate and accumulate a never-ending cacophony of smothering objects. The mannequin figures represent an idealized form of womanhood: unaging, devoid of imperfections, silent. Despite their endless dedication, they disappear into the background of their own creation, their bodies swallowed up by floral motifs and polka dots.

The playful backdrops and humorous tone juxtapose the violent positioning of the figures in the scene who are often visually decapitated, slumped over, or crushed. Carroll points to mid-century advertisements and movies and the game Clue as aesthetic inspiration. In every room, the women meet a terrible end. It was Janice in the kitchen swallowed whole by her oven, or Christine in her parlor strangled by boho blankets. The work contains an inevitable campiness born from these aesthetic inspirations. The dystopian nostalgia that accompanies a 1950s ad declaring “successful marriages start in the kitchen!” pervades every photograph. In one image, a woman sits in a kitchen littered with pies and tarts surrounded by a claustrophobic array of red checkers, doilies, and fake fruit. Hair in disarray, oven mitts still on, and one of three rolling pins in the crook of her arm, her face is replaced by her latest cherry concoction. Like Sisyphus and his boulder, she is trapped in an inescapable “domestic disaster” endlessly, obsessively producing baked goods. Her goal is unattainable by design: she will never bake the perfect pie, she will never be the perfect housewife.

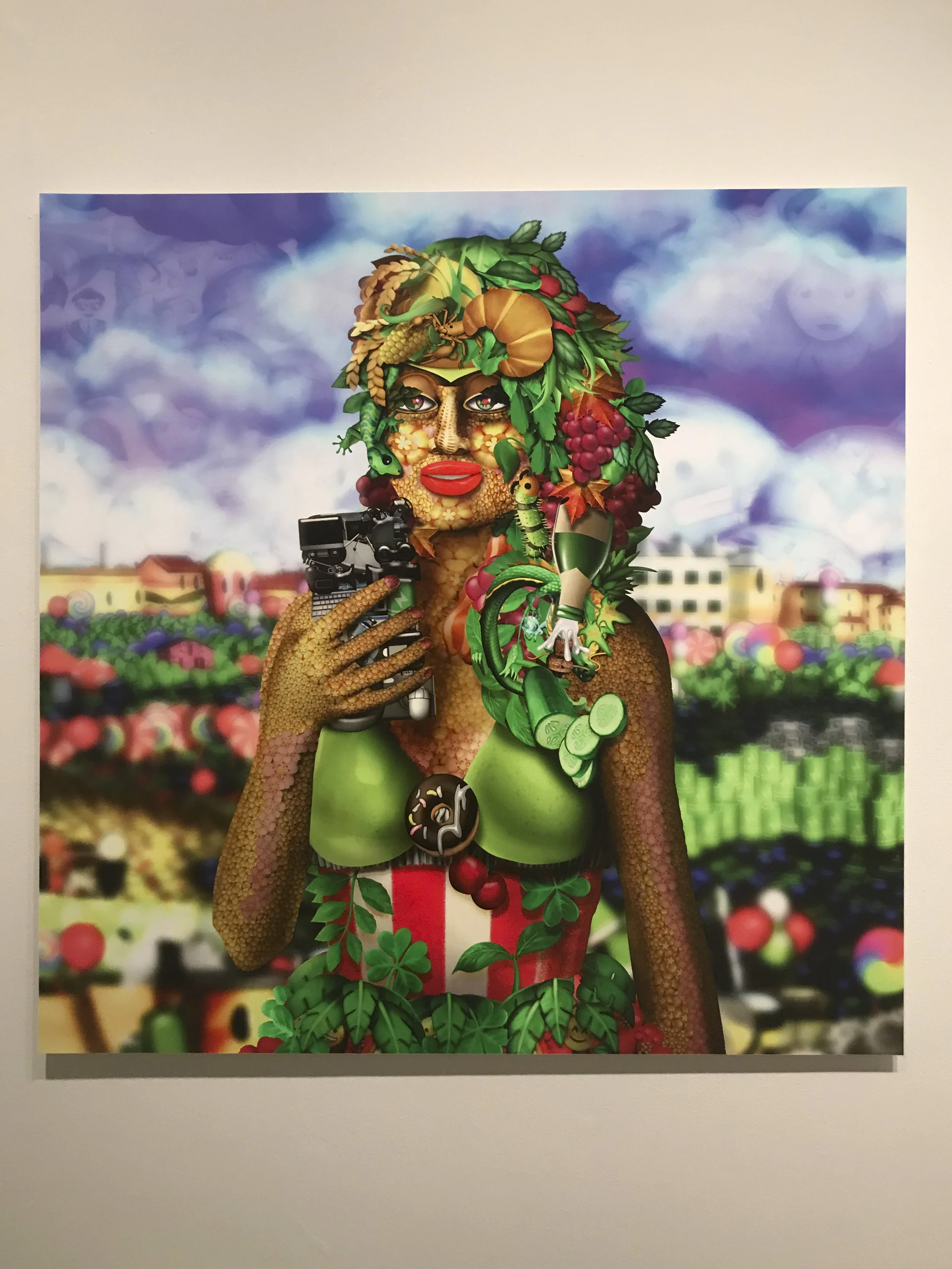

Mad Mauve

Carroll demonstrates the excesses of perfectionism to the point of absurdity. The tragicomedy of these overloaded domestic nests and the women who build them is that the search for identity ultimately leaves these women without one of their own. The saturated color palettes and humorous poses work strategically to draw the viewer into an unnerving game of benign violation. The comedy works in part because it is disturbing—a violation of our preconceived notions of what a glossy mid-century advertisement of a pristine home should be. That the femme figures are faceless, non-beings of plastic perfection make the violent situations they are placed in feel divorced from reality. The viewer is allowed for a moment to indulge in a gleeful brutality before slowly slipping into an empathetic pit of despair for Carroll’s women. The work is ultimately an exercise in uncomfortable introspection. Carroll’s work is constantly examining the meaning of home: an abstract reflection of human wants, needs, our desire for comfort. “Consumerism is aspirational, so it seems like we all want things in our lives to create identity. My women suffer from way too many things, as well as too many wants.”

This article first appeared in The Fiction Issue