On the drive back from this year’s Outsider Art Fair, I caught an interview on NPR with Andrew Edlin, the driving force behind the reinvigorated exhibition of self-taught artists from around the globe. The interview was part of a media blitz for this year’s fair, celebrating its 25th anniversary. It would be hard to imagine a better outcome from all the coverage. The advanced preview was packed and ran late past closing, and the scene was vibrant. In relative terms, photography was more thinly represented than some previous years, even if some remarkable work was still on display, which did leave me wondering what it means to be an outsider photographer, and how photography finds its way in the world of outsider art.

Winter Works on Paper’s yearly offerings of found photographs and ephemera is always a treat, and this year’s display leaned to the erotic more than I remember in previous years. Stephen Romano continues to show William Mortensen, and it’s hard to see how anyone can ever get tired of that imagery and the strength of the work. Galerie Lemetais had works by Miroslav Tischy, whose voyeurism still gives me the creeps even if the images are quite beautiful. Carl Hammer had a stunning display of Eugene von Bruenchenhein’s seductive portraits flanking a painting, and Andrew Edlin exhibited his work as well. Several booths had various displays of cabinet cards, tintypes, and glass slides. Jana Paleckova’s alterations of old photos, grotesque yet strangely witty, must have pleased lowbrow art fans and were featured by Fred Giampietro Gallery.

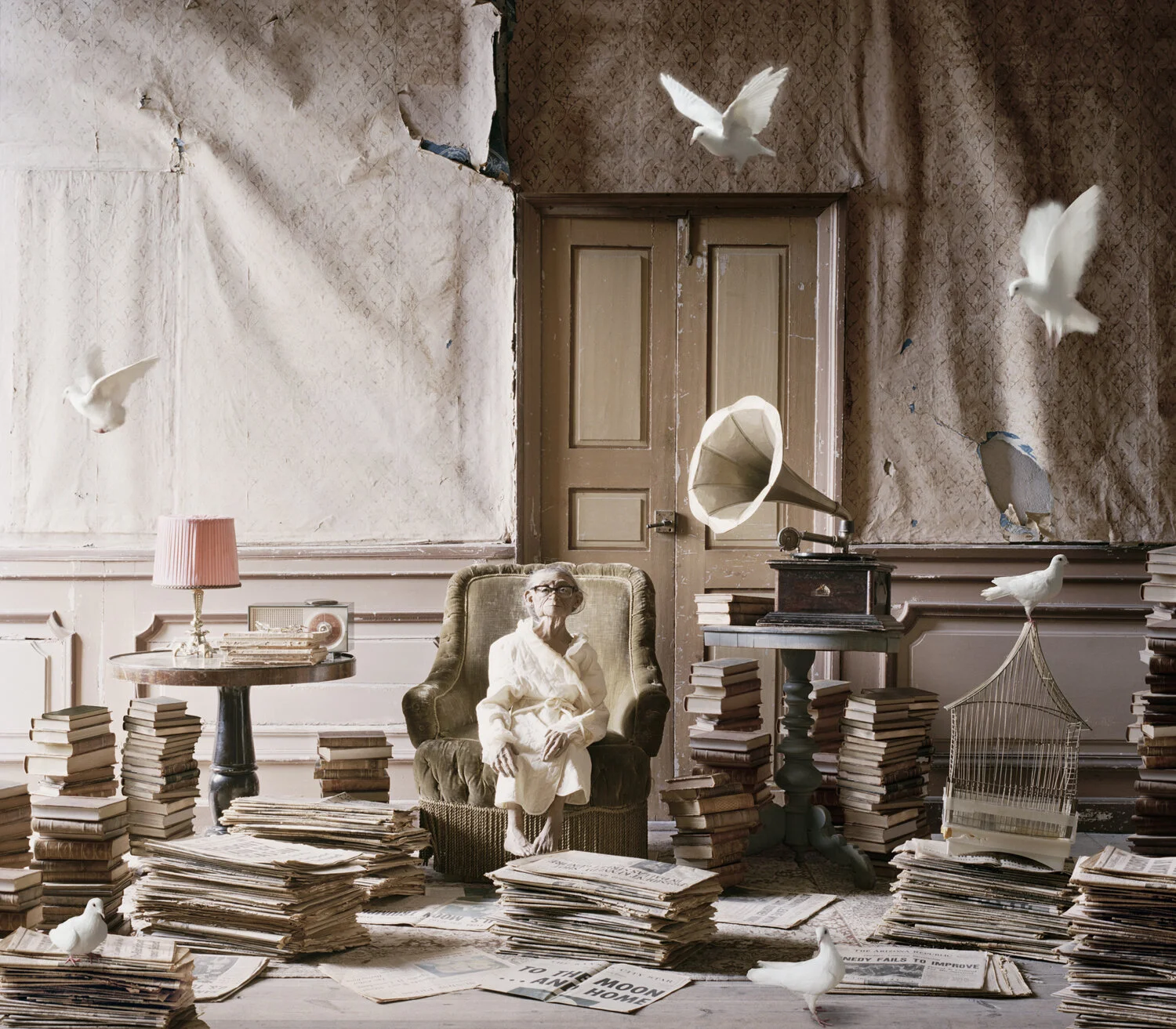

Ruben Natal San-Miguel's wall at Y Gallery's booth. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Among the photography at the show, however, the highlight was Ruben Natal San-Miguel. Exhibited by Y Gallery, Natal San-Miguel’s photos drew crowds and prompted conversation. Viewers wanted to get close to the images, and, I got the sense, to the subjects in the portraits. The photos convey a relationship and offer an invitation, not just through strong control of light and color, but through intimacy. If we don’t immediately recognize the people in the images, we yearn to know their stories.

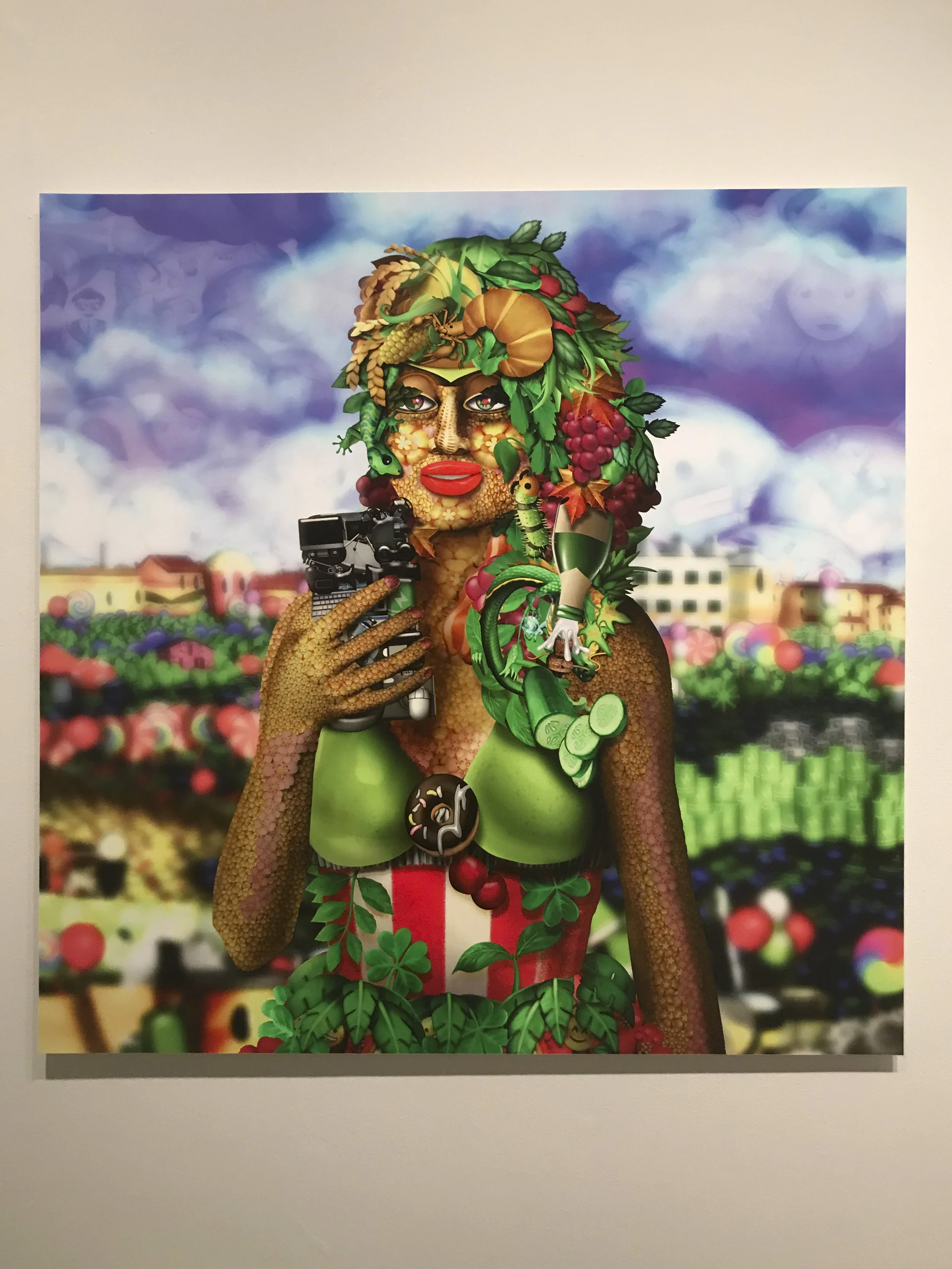

A similar yearning for story drew people into One Mile Gallery’s exhibition of Mark Hogancamp’s world of war. Staging action figures in scenes, Hogancamp makes photographs that teeter on the line between real and imagined. The large format images appear to be documentary, recording intimate moments in a supposed global conflict, but they are in fact part memory and part fiction of their creator. They do not attempt to fool the viewer—there is no doubt that these are figures posed in scenes. But they remain serious, and are neither fanciful nor clinical. They don’t feel real, yet they nonetheless unsettle. They feel true.

One Mile Gallery director discussing Mark Hogancamp's work. Photo by the author.

Outsider art has for years faced down the specter of definition. And whether it can linger there in any lasting way. Various groups have tried to give final answers of what it means to be an “outsider artist,” only to be met by work that challenges assumptions or broadens the field. As the field has gained wider acceptance, some within the community have lamented the loss of the “pure” outsider artist, a vision of a person wholly untouched by the art market. While the outsider is in some ways, as Edlin discusses in his smart interview, always insulated from the greater art world, in today’s world, the pure visionary or locked away artist becomes harder locate, let alone affirm as fully and completely outside artistic traditions.

Such facts suggest something especially difficult in trying to define a photographer as an “outsider.” In the age of Instagram, where anyone can send their photos out into the world regardless of training or background, is there any meaningful definition of outsider artist? If the limiting quality that most matters to be labeled “outsider” is lack of artistic training or lack of deliberate attempt to participate in the art market or in artistic traditions, Instagram nonetheless still offers up thousands, if not millions, of potential outsiders. There must be more to the terminology. There is an aesthetic, and, I think, an ethos. The story of the outsider is part of what constitutes the definition, and it’s precisely why the field is so rich and, to my mind, beautiful.

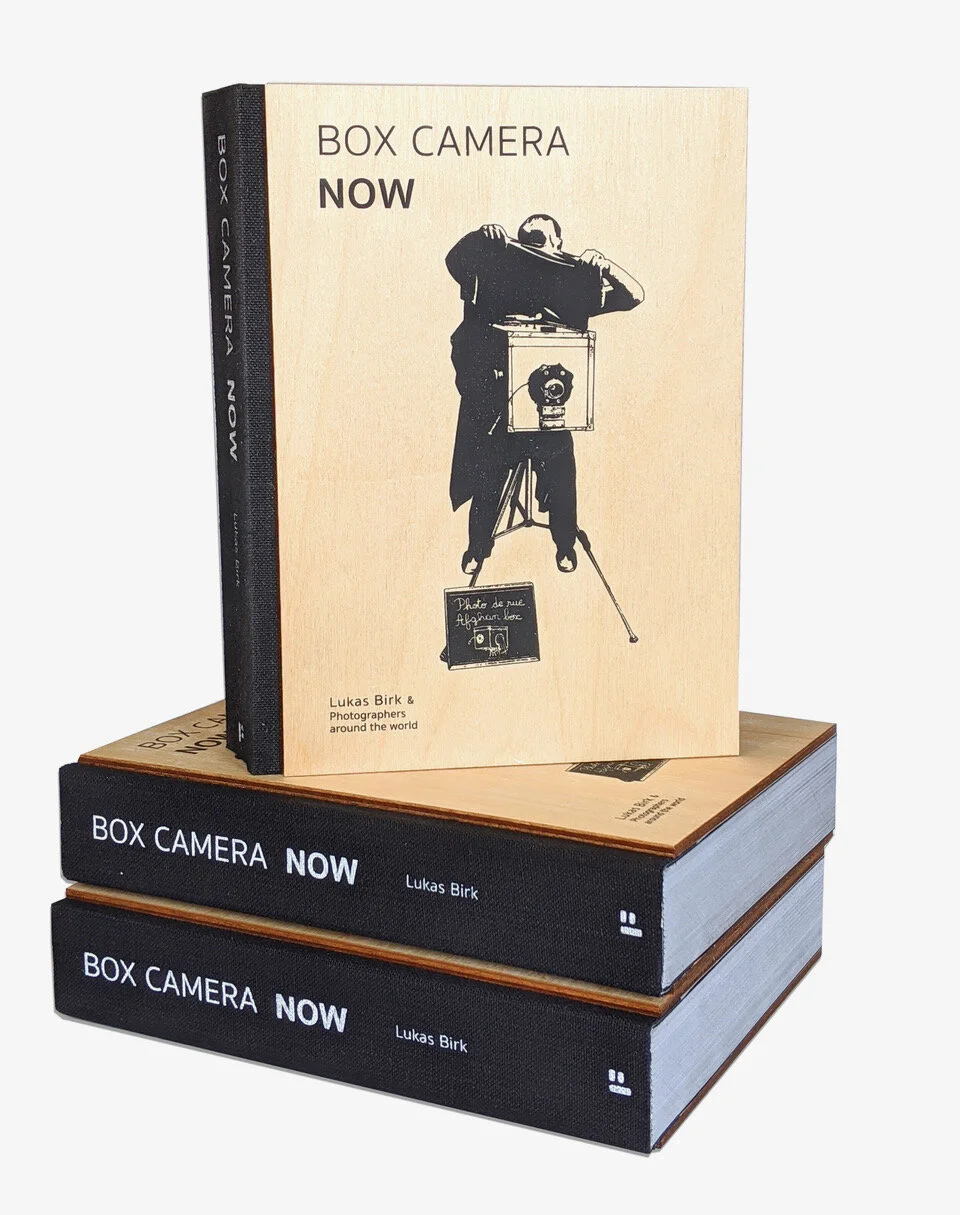

Frank Walter paintings on discarded Poloroid cartridges. Photo by the author.

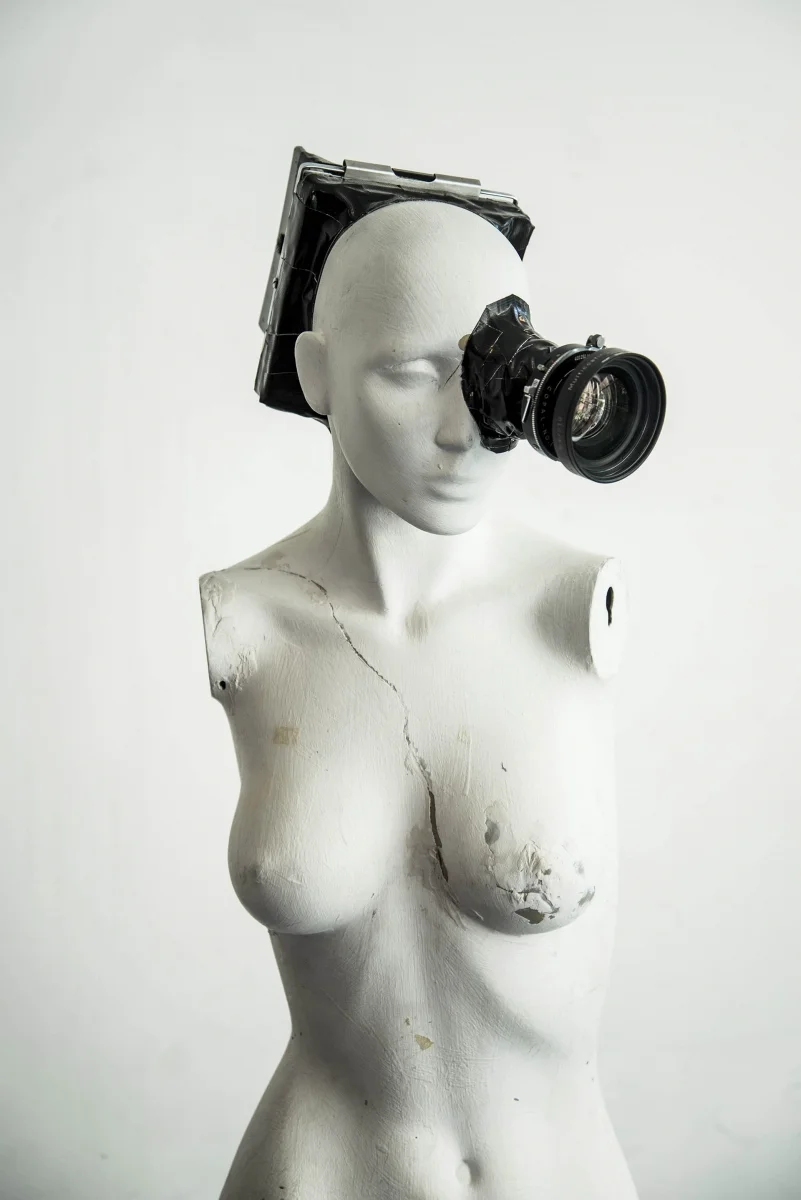

Hirschl & Adler Modern showed Frank Walter, whose work highlights some of these dilemmas of definition of outsider work. Walter’s work includes a series of paintings on cardboard inserted into discarded Polaroid plastic cartridges. It turns out that Walter was a photographer, at least by trade. He took portraits of people and took passport photos for them. In the exhibition is a photograph of Walter standing outside a small building, which has a sign that calls it his “Photo Studio.” In a kind of classic outsider story, Walter sequestered himself away on a remote part of Antiqua in a shack he built by hand, which had no electricity or running water. There, he painted, made photographs, used photographs as foundations for his paintings, and wrote reams upon reams of memoirs that figure himself, a black man living isolated on a Caribbean island, as Scottish royalty. Whether Walter is an “outsider artist” is not much in question. Whether his photography falls in that category, however, is unclear.

And that, perhaps, is part of the mystery that keeps me searching year in and year out at the OAF not just for paintings, drawings, and sculptures, but photographs whose stories elevate the work from pretty picture to sublime creation. I find myself less and less concerned with the labels or definitions applied to different artists, even if I recognize the value of distinguishing outsiders as different than more traditional artists. If for no other reason the label reminds us that the artistic spirit, despite attempts to shut it down, persists and grows in sometimes the most barren environments.

Roger Thompson is Senior Editor for Don't Take Pictures. His features have appeared in The Atlantic.com, Quartz, Raw Vision, The Outsider, and many others. He currently resides on Long Island, NY, where he is a professor at Stony Brook University.