It has been said that no single person is more responsible for Christmas as we know it than Charles Dickens. A Christmas Carol appeared in bookstores on December 19, 1843 and by Christmas Eve the entire first printing of 6,000 copies had sold out. Nearly 175 years later, the beloved story continues to be adapted for stage and screen, and read by millions around the world. The incredible success of A Christmas Carol earned Dickens the kind of celebrity status usually reserved for today’s international movie stars. This unprecedented celebrity coincided with the rise of photography.

In celebration of the 150th anniversary of Dickens’s famous reading tour of the United States, the Morgan Library has curated Charles Dickens and the Spirit of Christmas. The exhibition presents together for the first time the Morgan’s original manuscript of A Christmas Carol as well as the manuscripts of four more Christmas novellas—The Chimes (1844), The Cricket on the Hearth (1845), The Battle of Life (1846), and The Haunted Man (1848). In addition to the manuscripts, the show presents illustrations and letters related to the books, Dickens’ life as a literary giant, and even his writing desk. It also boasts a number of photographs, the significance of which has been overlooked by many photography historians.

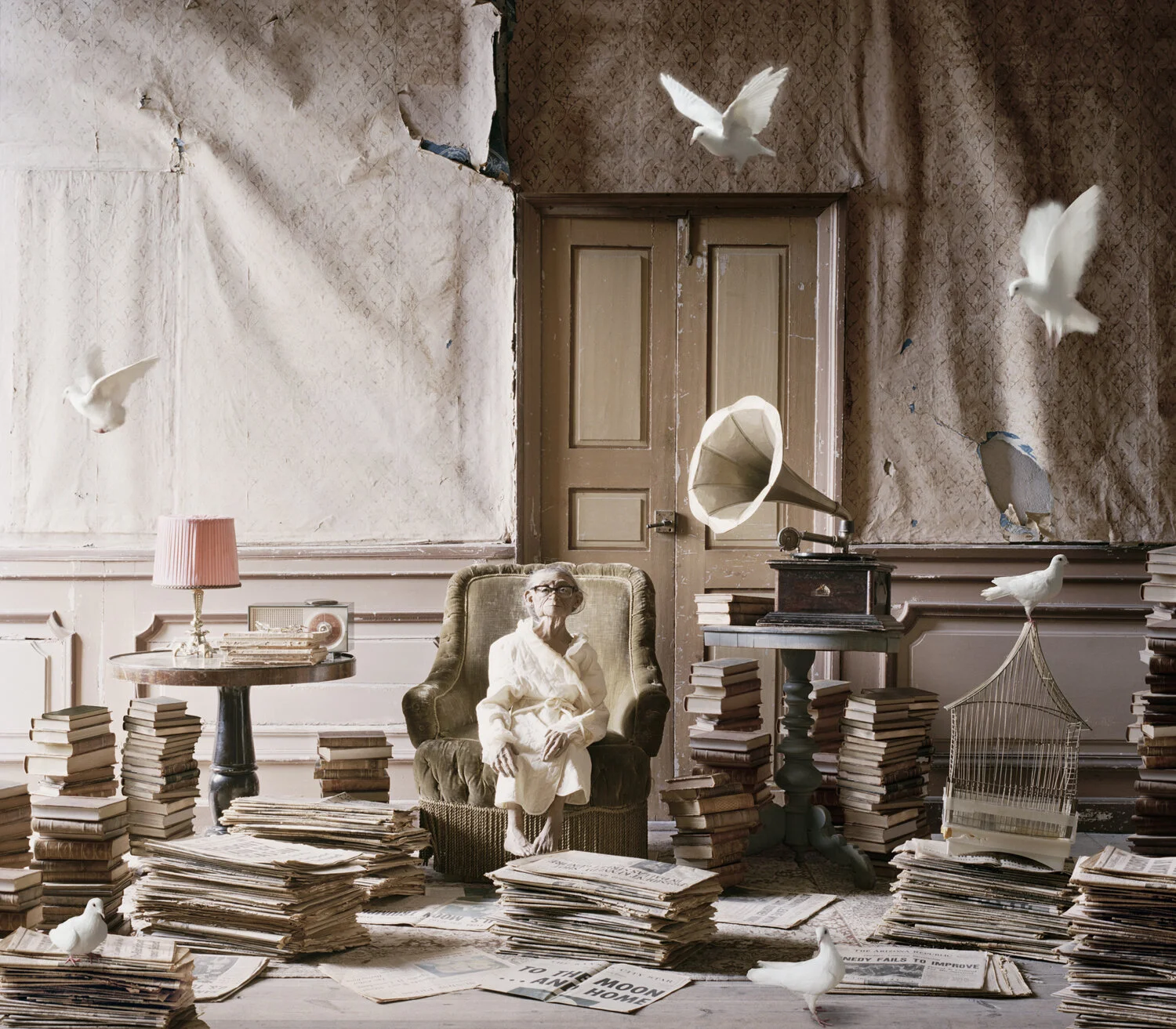

London Stereoscopic & Photographic Company, Charles Dickens, 1867, black and white photographs, The Morgan Library & Museum.

From 1858 to 1860—the years of “cartomania”—photographs of Dickens became much more readily available than before. Carte-de-visite photographs produced in huge quantities to satisfy the demands of the author’s adoring public, made him immediately and easily recognizable. According to Joss Marsh, he is considered to be the period’s “most photographically famous person outside the royal family” and “the first photographically mediated celebrity of modern times.” Dickens generally disliked being photographed—perhaps because, as the biographer Peter Ackroyd noted, “in middle age Dickens looked much older than he really was, having been wearied by a life in which he had contributed the work and energy of ten men.” These carte-de-visite portraits taken between 1860 and 1863 confirm this vividly.

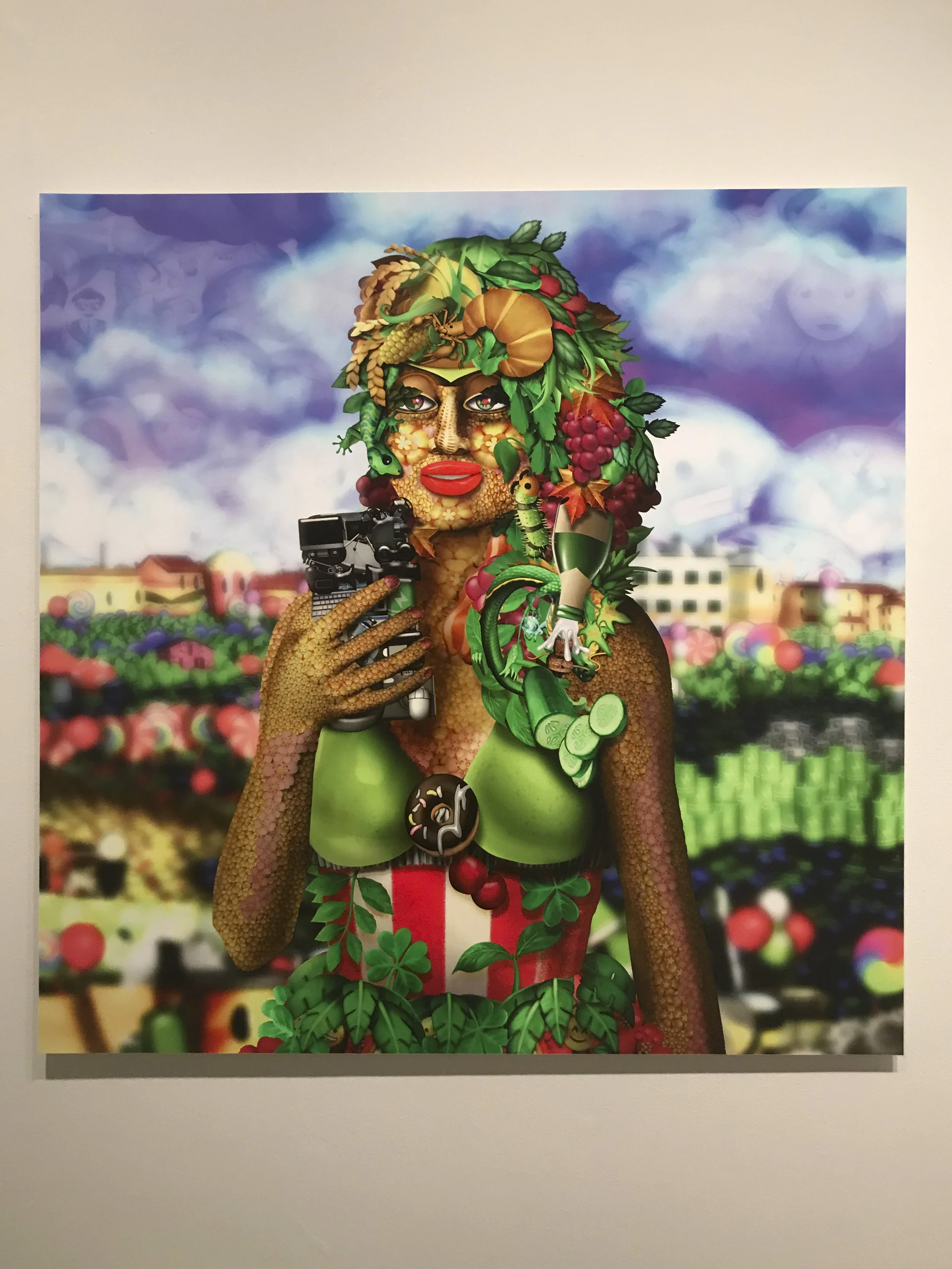

Jeremiah Gurney (1812–1895), A Portrait Signed in New York, 1867, black and white photograph, The Morgan Library & Museum.

Gurney, New York’s preeminent commercial photographer, was granted exclusive rights to photograph Dickens during his 1867-68 reading tour. Although this portrait is signed by Dickens and dated Wednesday Fifteenth April, 1868, he sat for Gurney on 9-10 December 1867. It portrays Dickens much as Mark Twain described him in his account in the Atla California newspaper on 5 February 1868, with “gray beard and moustache, bald head, and with side hair brushed fiercely and tempestuously forward.” Twain, who attended Dickens’s New Year’s Eye reading at Steinway Hall in New York, commented that “his pictures are hardly handsome, and he, like everybody else, is less handsome than his pictures.

Jeremiah Gurney (1812–1895), Charles Dickens, 1867, black and white photograph, The Morgan Library & Museum, MA 7793. Purchased for The Dannie and Hettie Heineman Collection as a gift of the Heineman Foundation, 2011.

This portrait photograph of Dickens, grandly attired and standing at a Davenport desk with a book in his left hand, was made at Gurney’s New York Studio in December 1867. Of the twelve poses that Gurney photographed, most of the portraits available to the American public—eager to acquire an image of the great novelist as a memento of his extensive reading tour—were carte-de-visite prints of this larger, more expensive “imperial” cabinet card print. After his protracted session at Gurney’s studio, Dickens—who detested posing for photographers—vowed he would never again allow himself to be photographed. No later photographs of the author are known to exist.

Charles Dickens and the Spirit of Christmas is on view at the Morgan Library and Museum through January 14, 2018.