“I never want to see another picture of ________.” Industry veterans share their pet peeves on themes in contemporary photography. In this series they present their “rule” along with five photographs that break the rule in an effort to show that great work is the exception to the rule.

Rule Setter: Mike Sakasegawa, host of Keep the Channel Open podcast

Rule Breaker: Brandon Thibodeaux

I’m always a little leery of making hard-and-fast rules, but one photographic trend that I would like to see less of going forward is facile photographs of communities of color made by white photographers. It’s not so much that I think it’s impossible for outsiders to represent marginalized communities, but it’s very difficult to make compassionate, sensitive, ethical images about a group of people you don’t belong to, and which you don’t understand. Empathy and imagination exist and are important, of course, but so do bias and blind spots—which is why it’s so critically important for us as artists and curators and members of the photographic community to make space for marginalized people to represent themselves.

Still, I believe strongly in the power of art to build bridges, and not just between art and audience or artist and audience, but also between artist and subject. More than that, I believe that it’s important for people who benefit from privilege to use what advantages they have to help, and to do things right. What would that look like, “doing it right”? Well, the first name that comes to mind for me is Brandon Thibodeaux.

I’ve been aware of Thibodeaux’s work for some time, but I never really took the opportunity to spend time with it until I saw him give a lecture at the Medium Festival of Photography last year. In his lecture, Thibodeaux talked about returning to the same communities in the Mississippi Delta year after year for almost a decade, forming real bonds and relationships with the families he came to know there. Later, in the conversation we recorded for my show, he talked about sharing birthdays and holidays with these same families, even driving their kids to school.

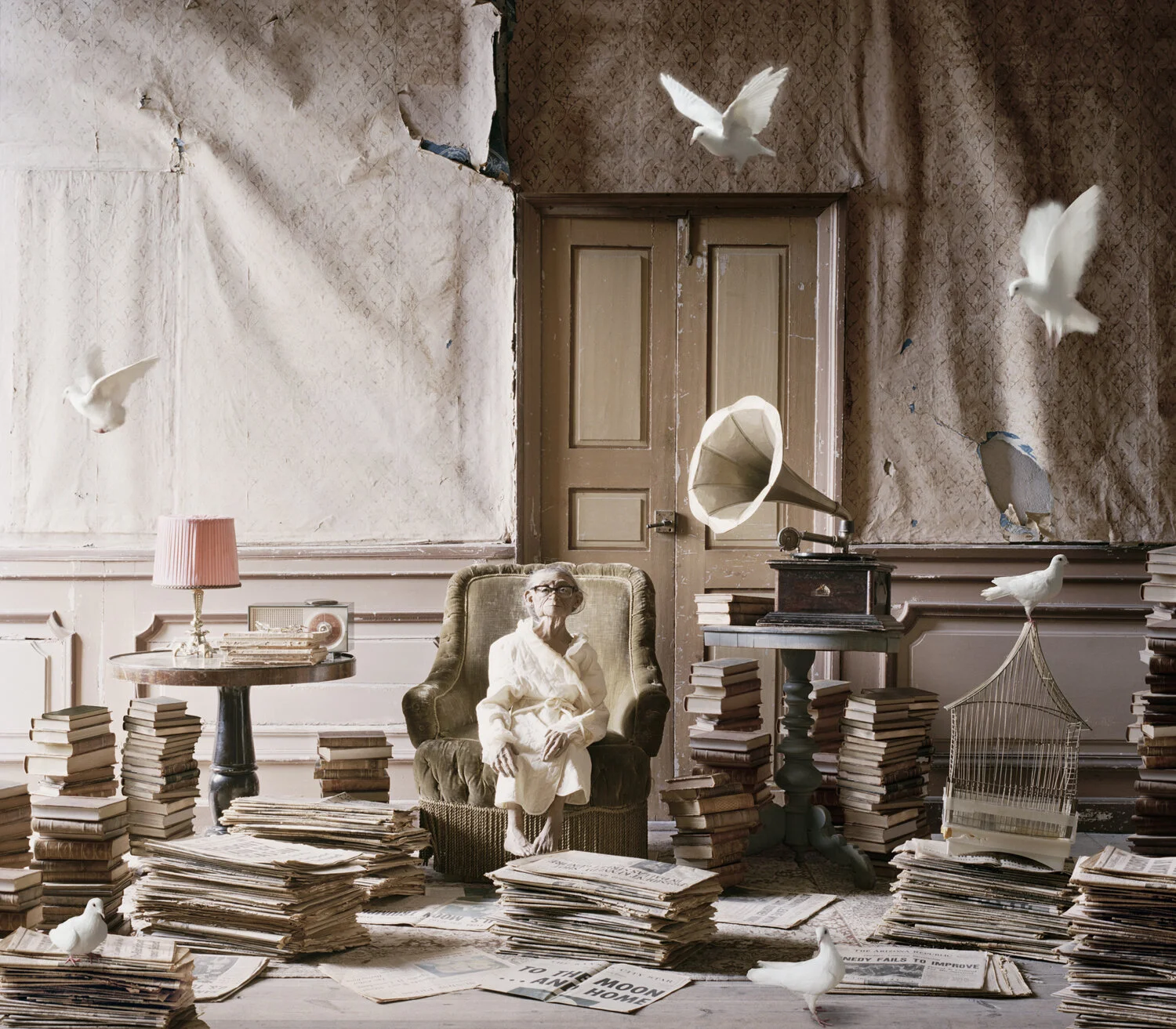

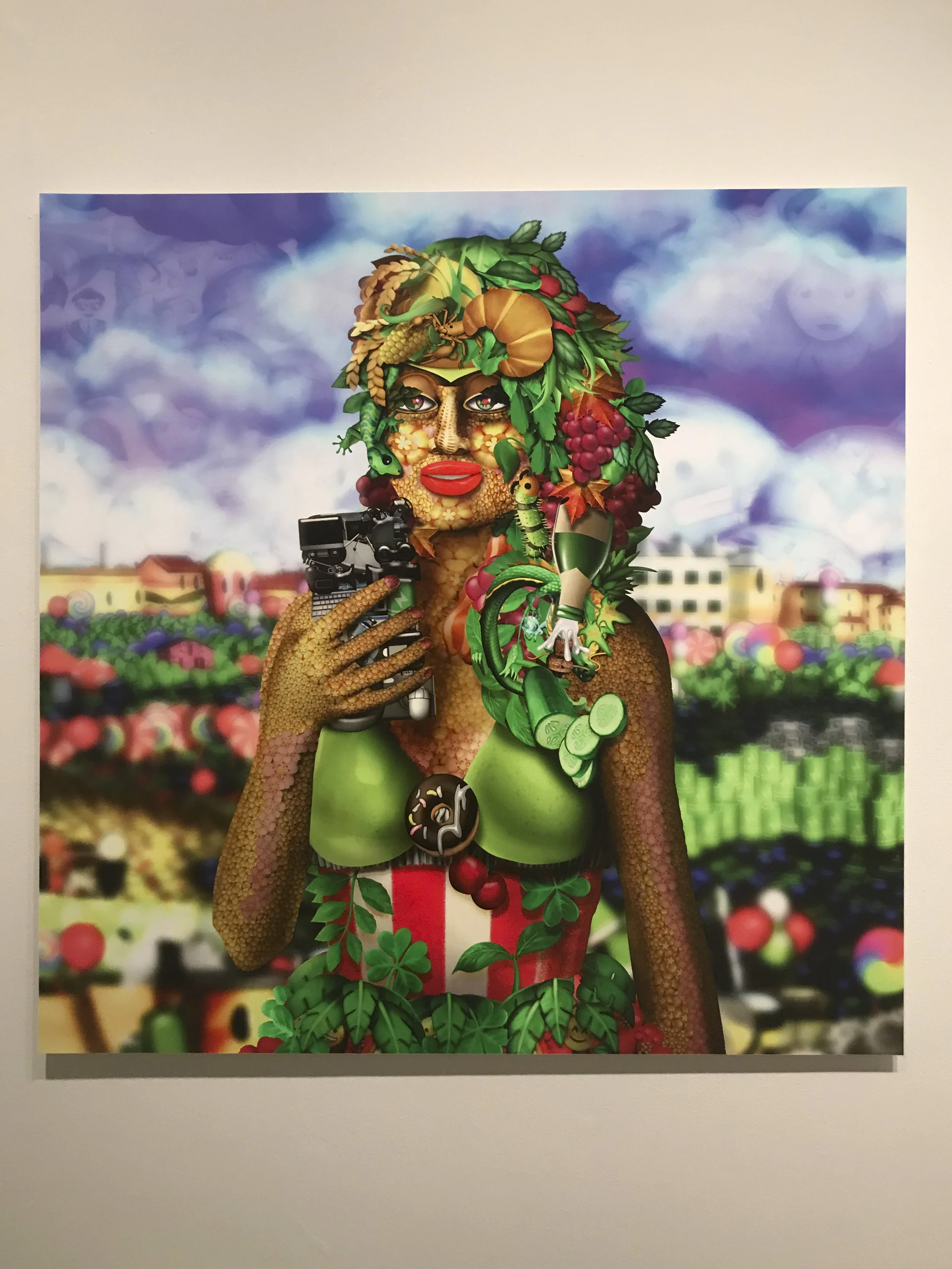

And it’s clear that these relationships have deepened the work, which I find to be empathetic and intimate. Many of Thibodeaux’s portraits were made not just in collaboration with his subjects, but at their direction, showcasing treasured personal objects or documenting a moment the true significance of which may not be apparent to anyone but photographer and subject.

I can’t claim that Thibodeaux’s experiences represent the one true way for white photographers to engage with communities of color. But my intuition is that any approach that really works is one that involves respect, trust, and humility on the part of the artist, and that’s what I see in Thibodeaux’s images.

— Mike Sakasegawa