The MetroShow continues to creep toward outsider art, contemporary—even low-brow—art, and art brut, yet while it does, it somehow manages to keep a firm foot in the past. It maintains a charm that so many shows lack, one probably rooted in its history as a folk and decorative arts mecca. Historical artifacts ranging from vintage toys to remarkable flags from the early years of the Republic sit alongside carnival signs, tramp art (the remarkable tramp art collection shown by Clifford and Nancy Wallach is almost impossible to convey in words), and all manner of gems that the word “antique” doesn’t quite capture because it loses the rich artistic expression to be found here.

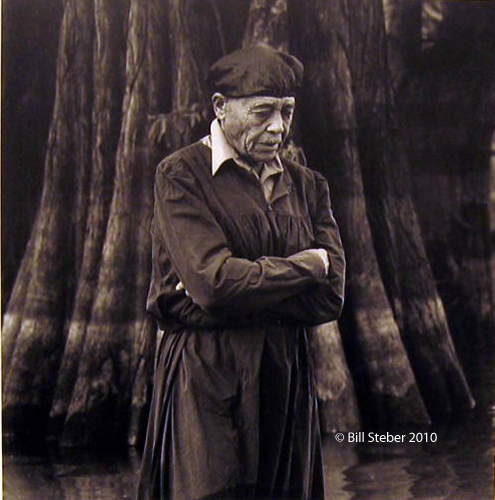

Frank and Bottle Tree ©Bill Steber/courtesy of Carl Hammer

Baptism II ©Bill Steber/courtesy of Carl Hammer

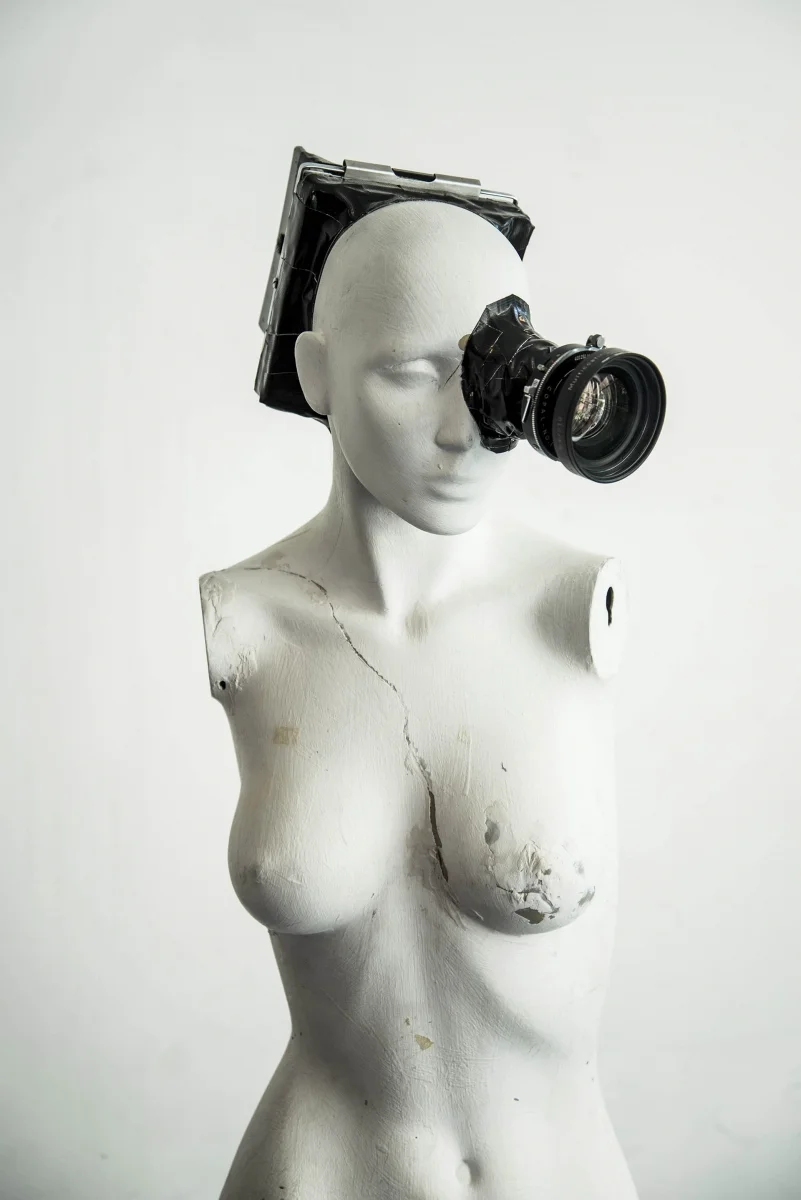

MetroShow makes no claim to being a photography show, yet, just as in previous years, fans of vernacular and fine art photography will find plenty to see. Stephen Romano continues to challenge the boundaries of fine art and outsider art, and his exhibit this year included both William Mortensen and Rik Garrett from his recent successful gallery shows, and here at Metro, he also showed the work of Ellen Stagg, a photographer whose work blurs the distinction between maker and consumer of erotica and pornography. The Pardee Collection, by contrast, exhibited the architectural photography of Barry Phipps. The images capture the color and lines of Phipps’s rural Midwestern landscape, and they illustrate a keen eye for contrasts, wedding past and present by juxtaposing architectural elements with their surroundings. In “Boyden,” for example, the rear of a midcentury car emerges from the glossy, manufactured white lines of a vinyl fence, and in “Iowa City,” a bold yellow shed draws its force from its contrast with the jumbled lines of an empty stadium behind it. These images hung alongside the barn drawings of Jim Work, a disabled man who works in crayon, and the pairing could not have been more striking.

Maling Shoe ©Bill Rauhauser Photography LLC/courtesy of Hill Gallery

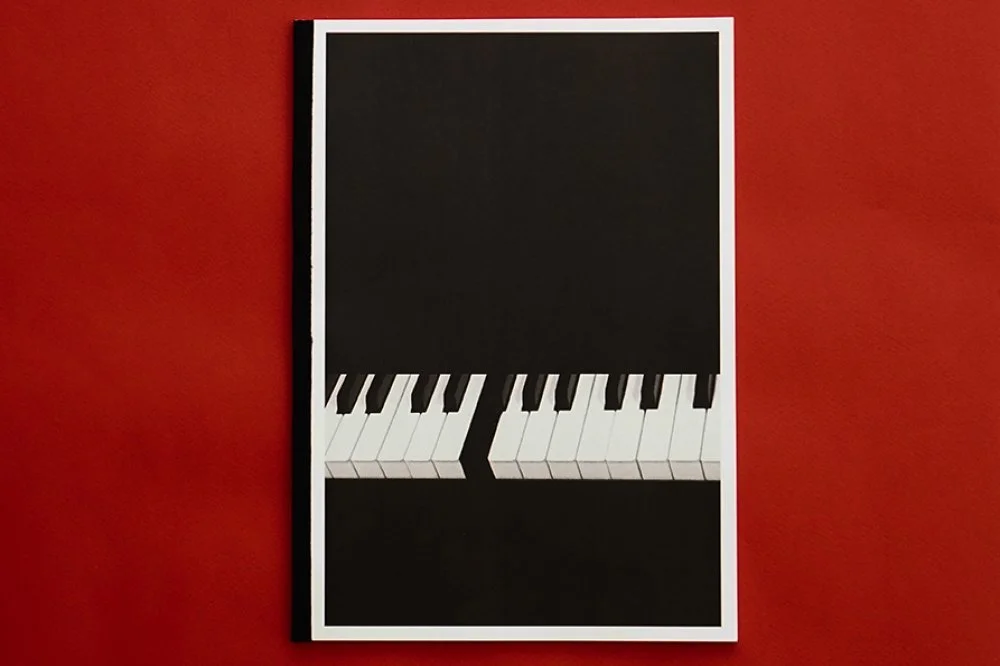

While Pardee’s booth was bold with color, texture, and composition, other booths were more intimate. Carl Hammer was exhibiting the work of Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, even though Bill Steber’s photographs drew just about anyone’s eye who walked past. “Baptism II” and “Frank and Bottle Tree” demand attention, and each time I walked past the space, the area in front of Steber’s work collected onlookers while Maier’s work, intimate as they are, seemed virtually empty. Hill Gallery returned with more images from Bill Rauhauser, whose work hung both in the gallery’s booth and on wall space within a public seating area. His image, “Maling Shoe,” hiding a bit in that latter retreat, was as compelling as any of the others.

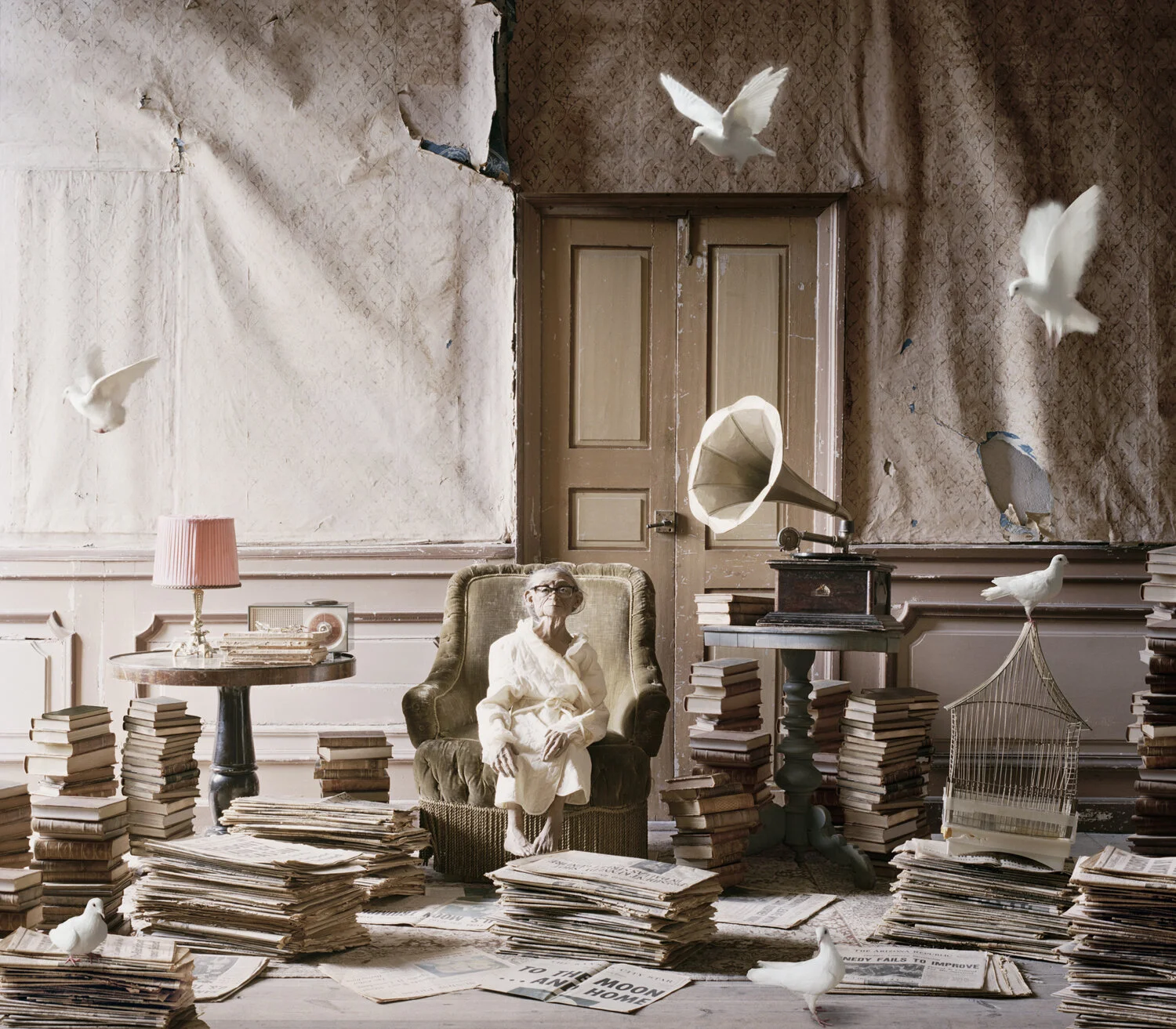

Swirl ©Nicholas Whitman/courtesy of Umbrella Arts

Relic 10 ©Elyse Defoor/courtesy of Umbrella Arts

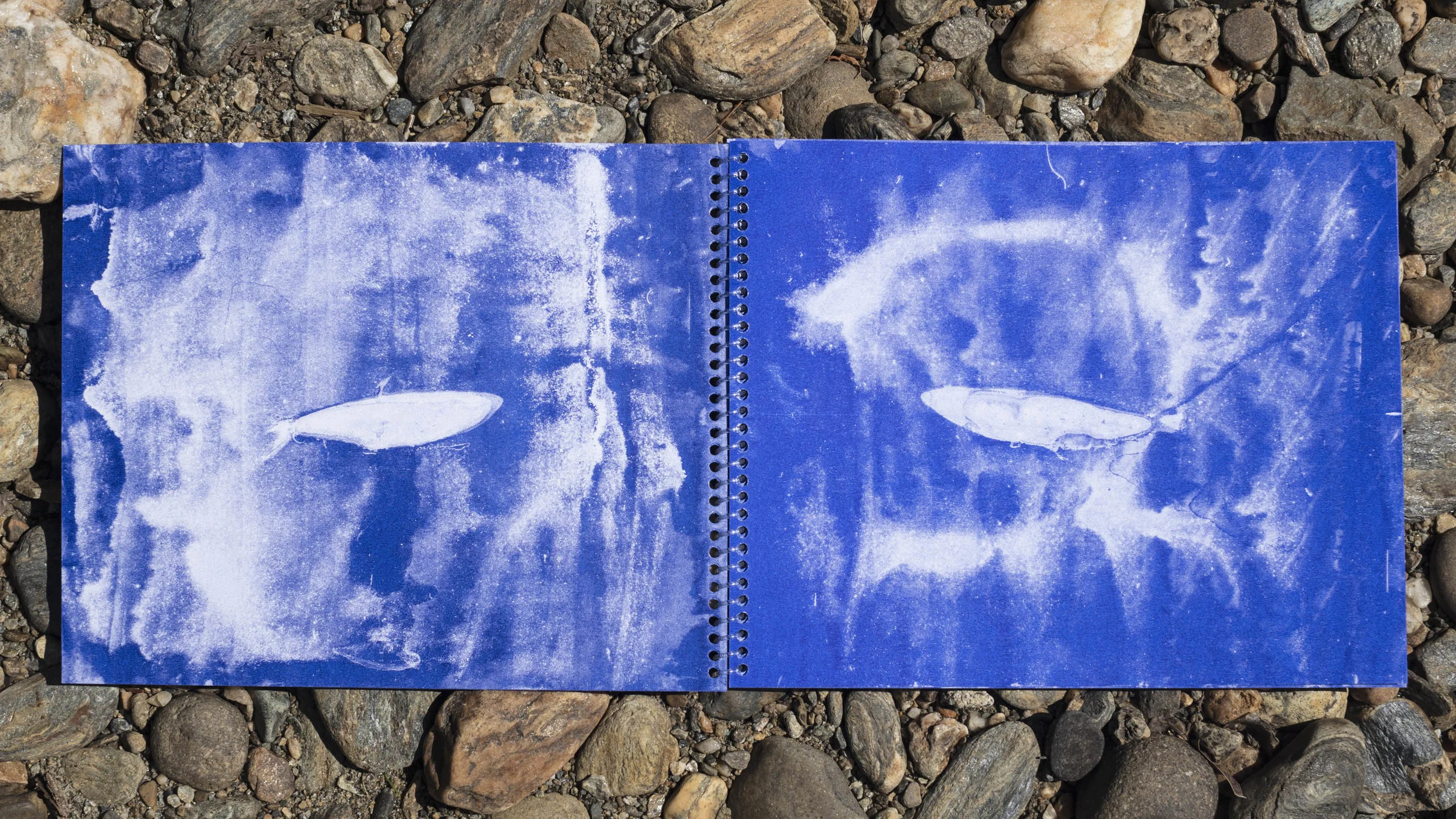

All of these provided ample fare for any fan of photography, but it was the variety and the striking power of the images hung by Umbrella Arts that stole the show. Hung together were images so diverse that the booth ran the risk of being a jumbled mess. And yet, it wasn’t. Instead, it was like a carefully orchestrated dance, with each piece somehow connecting with the others. I’m not quite sure how they did it. It may be that I simply liked some of the work enough that I’ve forced some coherence in my imagination, but I don’t think it’s the latter. Complicated, abstracted images by Nicholas Whitman hung alongside precise and haunting images by Elyse Defoor. Whitman’s “Swirl” photographs document the spinning of hundreds of fish beneath rippling water, and Defoor’s beautiful images of wedding dresses for her series, “Relics of Marriage,” rely on stark contrasts between the luminescence of the dresses and a dark void surrounding and behind them. The images glow, but they do not romanticize. Something lost hovers over them. Something desperate, and you get the sense that whatever remains of the marriages they represent, they can’t return to something left behind. The images evoke yearning for lost union, emblems for lost, if not unrequited, love. Next to these, Umbrella hung the charming but serious work of Suzanne Révy. “Evolution” is the highlight of the Time Let Us Play series, and while one can’t escape some echo of Sally Mann in the group, the images are too spontaneous and too, at times, joyful, to be reasonably compared. All of these, and others, Umbrella managed to show without minimizing one or crowding the others. The exhibit made sense, and the exhibitors themselves conveyed the passion of people who not only love art, but also the power of photography to transform our spirit.

Evolution ©Suzanne Révy/courtesy of Umbrella Arts

Roger Thompson is the Senior Editor for Don’t Take Pictures. His critical writings have appeared in exhibition catalogues and he has written extensively on self-taught artists with features in Raw Vision and The Outsider. He currently resides in Long Island, New York and is a Professor at Stony Brook University.