Ever since humans have been able to lift themselves towards the heavens, our view of the landscape has changed. Imagine the thrill of early sky explorers as they observed the world from on high for the first time; to see flattened patterns of structures and landscape rather than the familiar horizontal vista. To add a camera to the mix and capture those views by the cumbersome collodion process was a tricky endeavor, but what a gift to those anchored below.

The first aerial photograph was made from a tethered balloon in Paris by Gaspard-Félix Tournachon in 1858—and we have had a hunger to see the planet from above ever since. Cameras attached to kites and carrier pigeons have given way to drones and the ubiquitous snap from the airplane window seat. And in fact, the bird’s-eye view is so common nowadays as to become nearly inconsequential. But in the hands of photographer Luc Busquin, we get a reminder of just how wondrous a thing it can be.

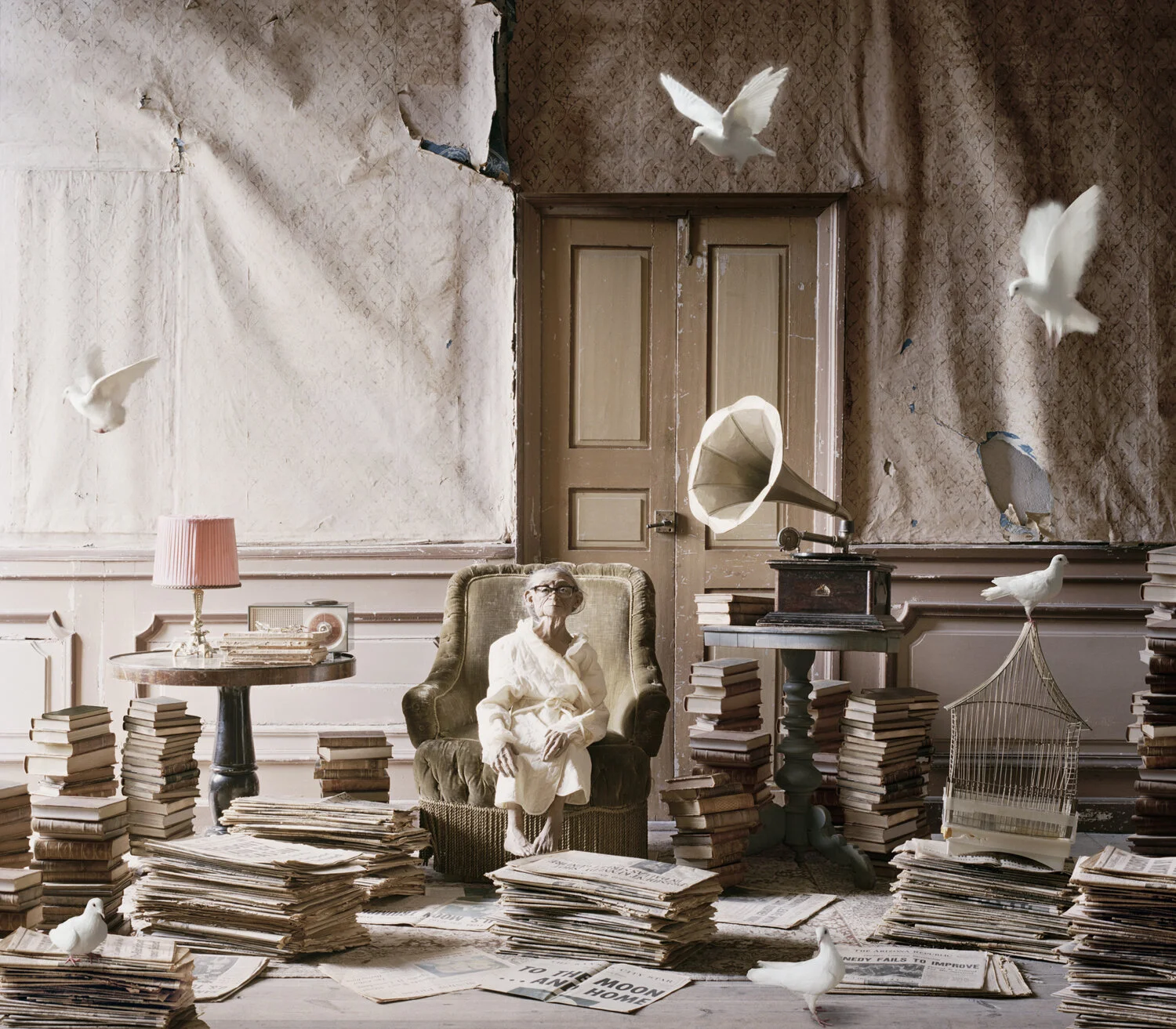

Colorado River Near Blythe

Born in Belgium with a passion for the sky, Busquin says that kites, airplanes, rockets, clouds, and stars have captivated him for as long as he can remember—a fascination that would lead him to learn to fly at the age of 16. Now living in Arizona, Busquin is a commercial pilot with a camera in hand; the grown-up version of a teen who once attached cameras to remote-controlled airplanes to shoot from the sky, as he did in his youth.

“Today, as a professional pilot, I am fortunate to experience the sky from within, to see the world below from that vantage point,” says Busquin. “Here is a place of different scale, colors and shapes whose great beauty I find irresistible.”

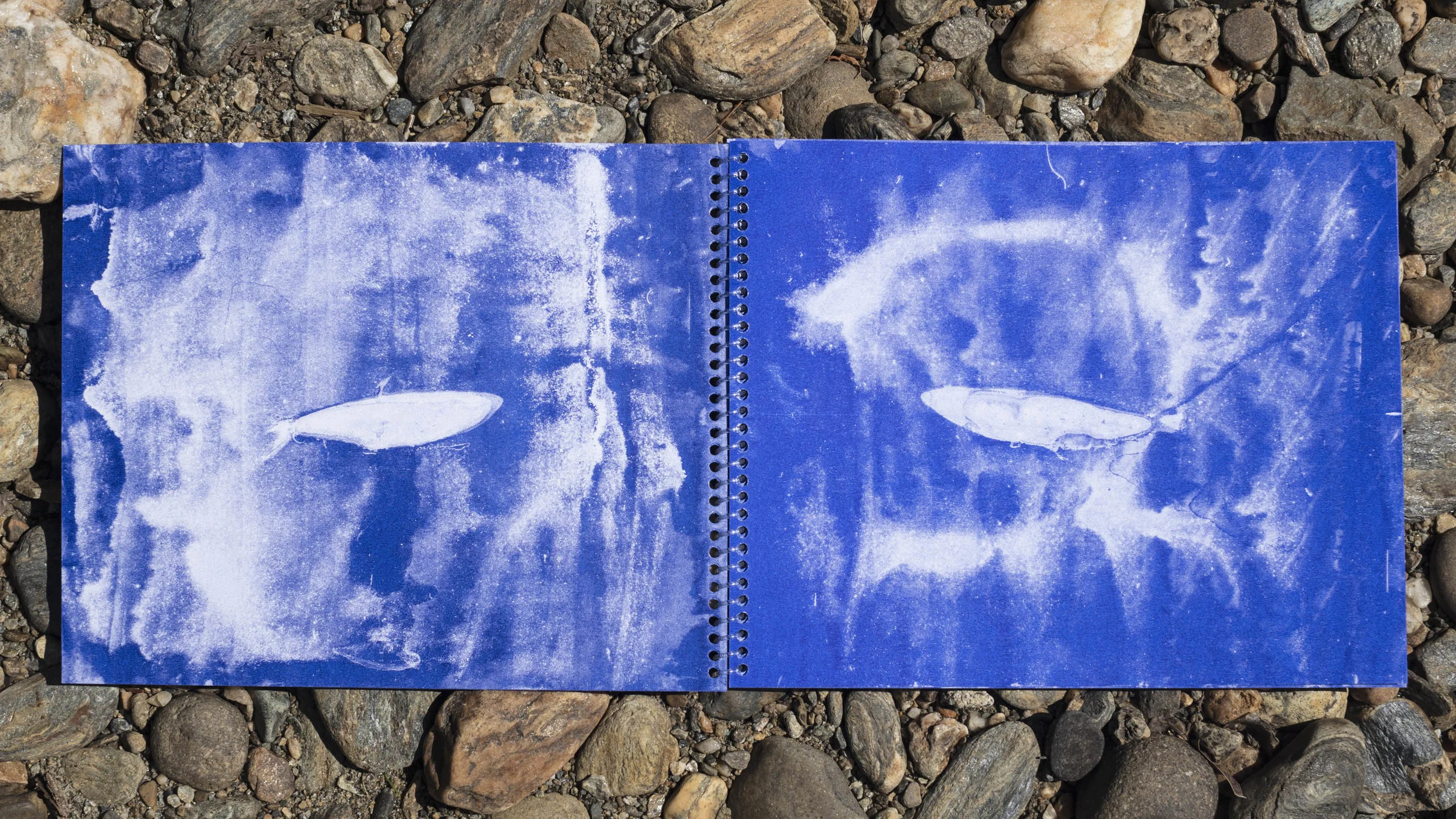

And indeed, in his series Atop the Troposphere, we see the world in a new light. We see the natural topography as well as the man-made, and where the two remain distinct and where they merge into one. From 35,000 feet, the ground becomes an intricate quilt of organic lines, often nestling the geometry of mankind’s footprint. Residential grids play off of winding roads and the orderly patchwork of croplands. Meanwhile, rivers step up to steal the show; meandering paths where water has etched its own history, revealing the intimate relationship of fluid liquid moving through the immobile landscape.

Escalante River

In speaking about his work, Busquin references author and aviator, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and his famous novella The Little Prince. That Busquin might find inspiration in the life and work of Saint-Exupéry is hardly a surprise. Saint-Exupéry had an ardent passion for flight and a firm grip on the importance of wonder.

From the early 1920s until his death in 1944, Saint-Exupéry flew all over the world; a pioneering airman who embraced adventure with the eyes of a poet. His novels and memoirs are replete with descriptions of mountains, deserts, rivers, stars and storms. And from them Busquin takes his cues. “This series of high altitude aerial photographs from the upper boundary of the troposphere, around thirty-five thousand feet, offers a perspective of our modern world influenced by Saint-Exupéry,” writes the photographer. “From that ideal height, the beauty of the natural world combines with man-made features to form mesmerizing scenes.”

And this is central to Busquin’s work; for while the views are enthralling, the way in which humankind has manhandled the planet is achingly evident. Busquin observes that today, more than 90 years after Saint-Exupéry first took to the sky, we can clearly see from above the enormous impact humanity has had on the environment through large-scale alterations of the land.

Missouri River and Omaha

For the time being at least, nature is somewhat holding her own in the United States; which is one of the beauties revealed in Busquin’s work. On one hand, Atop the Troposphere can be seen as an exposé of mankind’s proclivity to subdue the natural world. We see the scars and scribbles of our impact, indelible lines of pavement and progress. Yet the series also acts like a field guide to the majesty of nature, revealing where the planet prevails with terrain too brawny to tame. And even in the places that seem conquered by the rigid patterns of infrastructure and agriculture, nature effortlessly sneaks in to assert herself.

Views from the sky may be commonplace in the age of drones and jets and spaceships, but Busquin’s photos feel all the more urgent. It is easy to become immune to in-flight Instagram shots featuring filtered clouds mingling with suburban sprawl, but it is not easy to look away from the focus and poetry of Busquin’s photography. The work is unique in its meditative quality; the observations of someone who has spent countless hours musing on the land from above. He may not be shooting from a tethered balloon, but his images are no less a gift, and present a cautionary tale. For while the little prince had the magic to bounce around from planet to planet, we earthbound mortals have just the one. Putting it into perspective like Busquin has done, in all of its messy, mesmerizing beauty, is an endeavor we imagine would have made Saint-Exupéry proud.

This article first appeared in Issue 10.

Melissa Breyer is the managing editor of TreeHugger.com and a NYC-based photographer whose work has been featured by The New York Times and National Geographic. Her upcoming photo book will be published by Peanut Press in 2018/19.