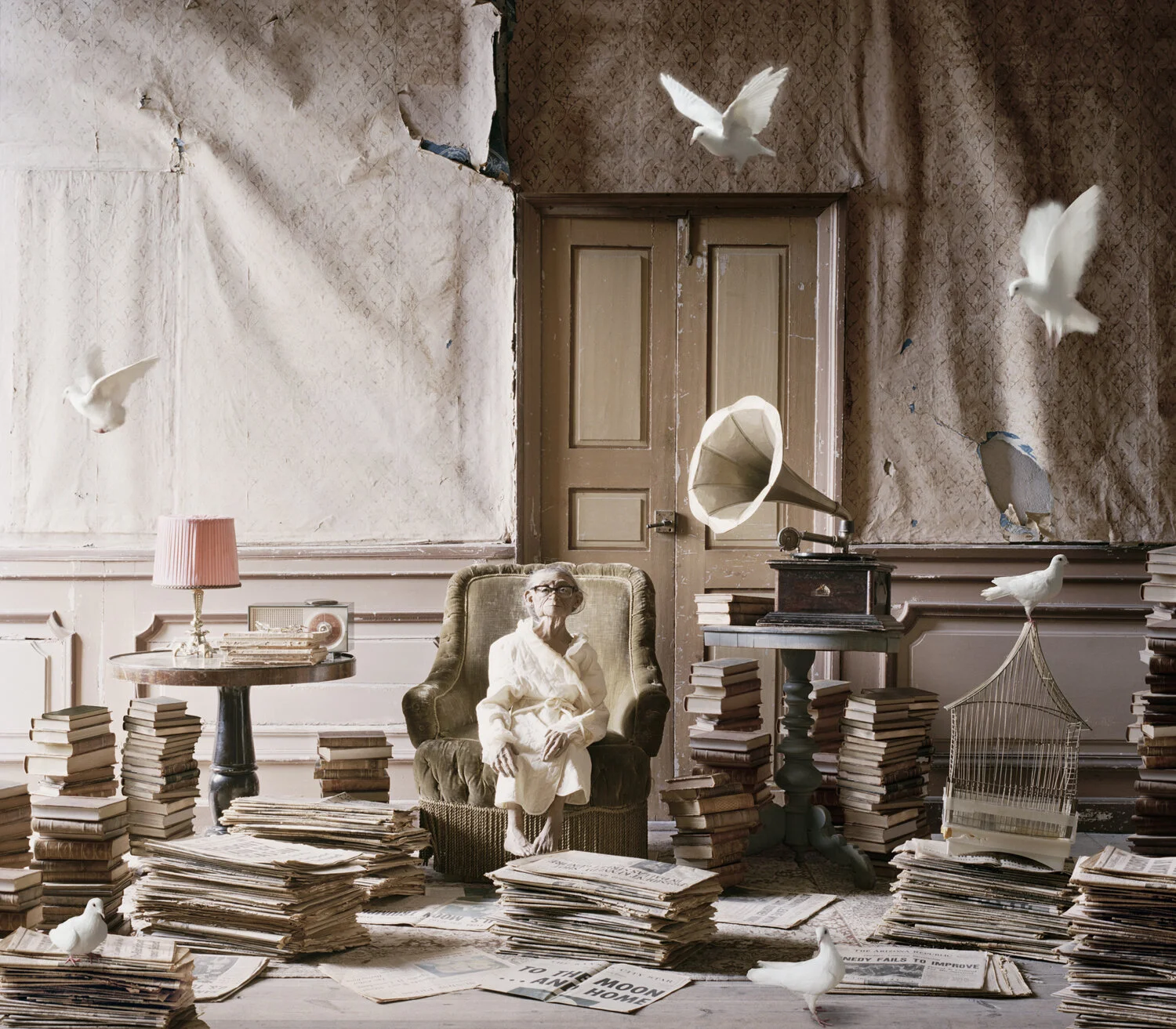

The woman in the picture is not really there. A hazy outline of her form is the only hint that she ever occupied the space at all. Though you cannot truly see her, you cannot see through her either. Like a memory, she leaves only an imperfect impression. This is one of the overarching themes in Jordanna Kalman’s series Invisible. Originally shot on Polaroid film, these altered photographs are a poignant revisiting and reworking of prior images, many of which were made as a part of Kalman’s MFA thesis work at the University of the Arts London.

The series was born out of the tragedies of death and loss. Nearly a year ago, Kalman unexpectedly lost her mother. Kalman had been working on another series, Sometimes (memory version), in which she removed the figures from the background of her older images, seeking to investigate concepts of fading memories and presence. But after the death of her mother, Kalman’s work shifted and she plunged deeper into exploring the relationship between memory and absence. Invisible explores absence in the context of memory, the past as it impacts the present, as well as the beauty of life and the knowledge of death.

Though Kalman works primarily with instant film, the creation of her imagery takes time to gestate. She describes her work as pseudo-diaristic with strong elements of fiction. The revisiting of older work, which was initially created in a similar vein, has plaintive connotations about how sorrow impacts both our remembered experiences as well as our experiences going forward. All of Kalman’s work deals with independence, individuality, loneliness and femininity. Yet within Invisible, these themes intersect with themes of grief and loss, asking the viewer to consider how we, and our memories, are defined by what is absent.

The series consists almost entirely of female figures that have nearly faded into the background or are portrayed without heads. In each photograph, an eerie sense of oppositions exists: the subjects are at once clearly outlined, yet are surreally absent at the same time. Unmistakably feminine, they lack a definitive identity. At their core, each photograph causes us to consider who we are when stripped of our identity, and to question the origin of those concepts. Often that sense of self is tied to our family, and in both the process of forging our own families or accepting death and loss, we are forced to reconsider those parameters and definitions.

With children of her own, Kalman found herself grappling with her role as a mother while grieving for the one she had lost. It was in her struggle to be present and the desire to retreat into a cocoon of grief that Kalman first began to feel invisible in her own life. Grief, especially in the context of death, takes us out of the daily flow of life. Like the figures in Kalman’s photographs, we can melt away into the background even as we try to pick up the pieces and carry on. But there is no comfortable place for grief in our society—we cannot sit Shiva until we feel the strength to stand up again. Life demands that we continue on. And so we do, perhaps feeling faded or without our wits about us. We are in the world, but not fully of it. We are, in fact, somewhat invisible.

In grief, our memories tease us. Loved ones are still alive in our memories; we drive past their former homes, near-convinced that they would answer if we were to knock on the door. There are times that we can still smell their perfume, or remember the feel of their hand in ours. But even those memories, ones that we rely on to keep alive that which we have lost, ultimately fade. In this sense, Kalman’s work causes us to examine the relationship between permanence and impermanence, and where they coexist. By stripping her figures of nearly all of their features, Kalman’s confronts the stark reality of our mortality, and asks us to question what we leave behind. Do we continue to live on in the memories of those we love; do we fade with those memories?

It is perhaps fitting then, that Kalman’s photographs are made with Polaroid film—an immediate and permanent record. For analogue photographers, Kalman included, the medium is important because of its physicality. Working with film engages all of the senses, making it a participatory and anchoring experience. Kalman’s use of instant film creates an expectation of an accurate record of reality despite her digital manipulation of the Polaroids. Just as we assume that our brains record our memories as fact, they too are manipulated. Whether by perception, time, or loss, an erosion of our minds can forever alter that which we once believed was accurate. In the photographs, Kalman’s hand acts as that altering force. But like our more haunting memories, or the residue of dreams, we see clues of what once was. Perhaps it is a hint that, even once gone, something still remains. Kalman’s work serves to reminds us that there is an impermanence to everything: the very film she works with that is increasingly difficult to find, the memories that define us, and our very lives.

Though we leave footprints wherever we go, especially in our increasingly digital world, it is sobering to consider that our imprint on this world could be removed just as easily as Kalman removes her subjects from the imagery that comprises Invisible. This forces us to wonder: where does our identity truly reside, and who are we when stripped of it? With these lingering and unanswerable questions, Kalman’s series serves as a subtle but effective memento mori.

This article first appeared in Issue 7.

Jen Kiaba is a photographer and writer based in the Hudson Valley, NY.