Every month an exclusive edition run of a photograph by an artist featured in Don't Take Pictures magazine is made available for sale. Each image is printed by the artist, signed, numbered, and priced below $200.

We believe in the power of affordable art, and we believe in helping artists sustain their careers. The artist receives the full amount of the sale.

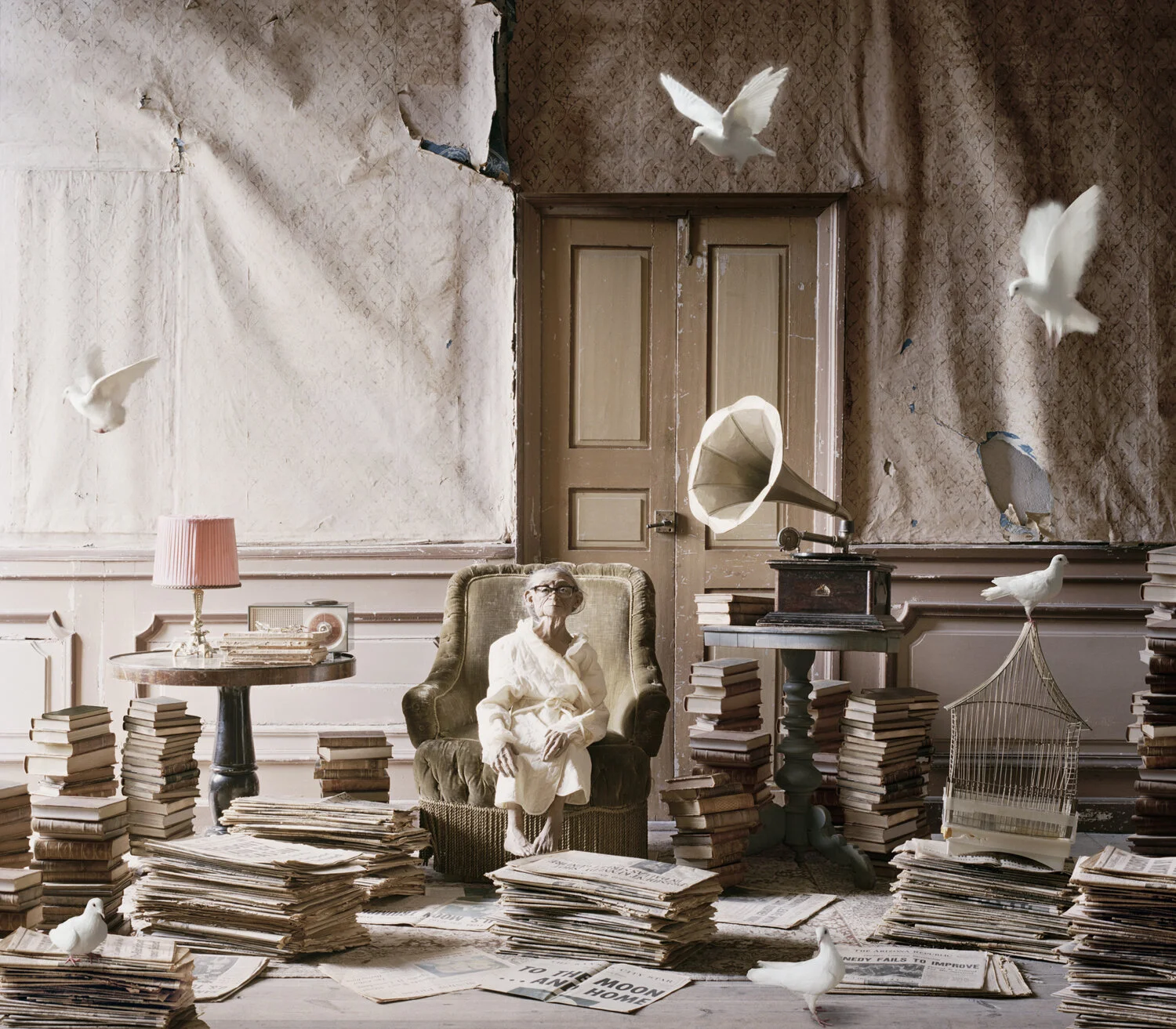

We are pleased to release January's print, “Professor Paul Smith, Director, Oxford University Museum of Natural History,” from Joanna Vestey. Read more about Vestey’s work below.

Purchase this print from our print sale page.

Joanna Vestey

Professor Paul Smith, Director, Oxford University Museum of Natural History

Archival pigment print

6 x 9, signed and numbered edition of 5

$150

The public is regularly invited to enter the great institutions of mankind—museums, universities, libraries, cathedrals—but rarely allowed a glimpse into their inner workings. The efforts of their guardians, curators and custodians are always in plain sight, in the careful assembly of fossils or the flawless polish of wood, all so often taken for granted or looked over completely. Joanna Vestey’s series Custodians lifts the veil of privacy, allowing us to perceive the synergetic relationships that shape these establishments.

Vestey, who lives and works in Oxford, England, was fascinated with the potential for photographs of storied locations to, “make a linear journey through time to consider the history and long-term importance of the spaces.” With the support of the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology at the University of Oxford, she allowed the many institutions that the she visited to choose her subjects, or “custodians,” for this series, from head curators to grounds managers. She spent time biking and walking around her city, leaning on the generosity of strangers to access behind-closed-doors areas, and spent over a year researching and visiting sites to distill her final selection of locations.

Michael O’Hanlon, Pitt Rivers Museum, 2013

While the titles, salaries, visibility and attributed value of the subjects’ roles vary greatly; Vestey’s photographs are a great equalizer. Similar to how August Sander’s portraits of the German populace in mid-20th century Germany depicted barons and butchers as equally imperative and honorable to society, Vestey’s work places those in the basement and the corner office on equal pedestals. Not only that, but the importance of the institution and caretaker are placed in perspective—with the institution’s expansive space dwarfing the individual.

From the soft-lit stacks of Oxford’s most celebrated library, to the inner halls of specimen-lined museums, Vestey purposefully illuminates her subjects in available natural light—sometimes glistening and luminous, other times shrouded and evasive. This masterful use of light is painterly, illuminated by single windows reminiscent of Vermeer masterpieces. The spaces seem unaltered and austere, presented to the viewer exactly as they are and without embellishment. This allows the spaces’ intrinsic wonder and depth to unravel with each new photograph, like peeling back layers of time and tradition.

Sister Ann Verena CJGS at Bishop Edward King Chapel at Ripon College, for example, stands erect towards the right edge of the frame. Her figure, weathered but proud, at once occupies the space and is absorbed into the surrounding sand-white pillars of the chapel walls. Her presence is keenly felt, the reserved but vigilant eye that keeps order, just one caretaker in a long line who have performed this duty. While others came before her and others will follow, the importance of her role in this chain is not diluted. She maintains the Chapel, just as it sustains her. Grandiose architecture aside, she is worthy of the same recognition.

Sister Ann Verena CJGS, Bishop Edward King Chapel, Ripon College, 2013

Vestey presents her subjects at a significant distance from the camera, which highlights the smallness of humans in contrast to the majestic and awe-inspiring spaces that they oversee. The scale of the rooms seem to engulf her subjects. Especially in Oxford, a place steeped in tradition and built on education, these compositions are an appropriate reminder that such spaces serve a purpose greater than that of any one person.

This is particularly evident in Vestey’s photograph of Su Lockley, Librarian-in-Charge of the Oxford Union Library. It takes a moment to even find Lockley in the tapestry of bulging stacks, thousands upon thousands of volumes in muted greens, reds, and blues beneath an arching maroon roof dotted with symmetrical windows. Lockley gazes down upon the stacks, empty tables covering the carpeted floor, her scale making her one with the books packed into each carefully ordered shelf. The image is filled with reminders of time and yet also seems apart from it—preserved from the past for the students of the present and the great minds of the future.

In her portrait of Michael O’Hanlon, Director of the Pitt Rivers Museum, he is surrounded by glass vitrines holding ancient pottery from around the world. His enduring posture is indomitable, as though he too was surrounded by glass. Dr. Jon Whiteley, Curator of the Randolph Sculpture Gallery at the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, sits steadfast between two rows of polished marble figures, himself assuming the grace and dignity of the figures he curates. In one of the more self-aware portraits, Professor Emeritus John Morris of the School of Anatomy at Oxford is clad in the same hospital blue that covers what might be cadavers on the gurneys surrounding him. Anatomical skeleton models dot the sterile space as he stares ahead, seeming to confront the fate that inevitably awaits him. Despite this, the image is less morbid and more elevated, a recognition that with education comes empowerment.

Su Lockley, Oxford Union Library, 2013

The relationship between caretaker and cared-for is multifaceted, but one recurrent theme is that of the fragility of mankind in the face of inevitability. The institutions are storied and permanent (or at least intended to be) but the lives of the people who tend to them are comparatively brief. As humans, we are here for a short while, and must make the most of our time before we pass the torch to our heirs, as our predecessors did unto us. This notion is humbling but never trivializing. Many of the subjects of Vestey’s photographs have been appointed to their caretaker roles for life, meaning great devotion and selflessness are required, something Vestey describes as “slightly monastic.”

Published as a book in late 2015, Vestey approached Custodians with the same devotion and appreciation for those forces larger as her subjects approach their work. To follow the photographs is in itself a monastic journey, forcing the viewer to take a moment to understand the ways in which we shape—and are shaped—by the institutions that we so often take for granted.

Evan Laudenslager is a photography-focused writer and artist based in Philadelphia, PA. He is a graduate of the Visual Studies program at Tyler School of Art, Temple University.

This article first appeared in Issue 7.