“I never want to see another picture of ________.” Industry veterans share their pet peeves on themes in contemporary photography. In this series they present their “rule” along with five photographs that break the rule in an effort to show that great work is the exception to the rule.

Rule Setter: Tom Griggs, photographer and educator, writer and editor of Fototazo

Rule Breaker: Francesco Merlini

I never want to see another black and white picture dominated by exaggerated high contrast and grain.

We train ourselves to almost immediately type certain photographic work as serious or not, as visually sophisticated or not, based on associations with other bodies of photographs we have previously seen and judged. In essence, we visually stereotype photographs against a back catalog of experience. It’s efficient. It allows us to process a lot of information rapidly. It saves us from having to repeat the same mental mathematics each time we’re confronted with a similar situation.

I paid my dues teaching Black and White 101 and sat in on untold undergrad critiques with students who discover this high contrast and grain aesthetic, a visual form of expression that seems—to them—true to their 20-year-old sense of rebellion or difference, who believe this mode of working taps into something raw and radically experimental, not knowing last semester’s student thought the same, as did the student from the semester before that.

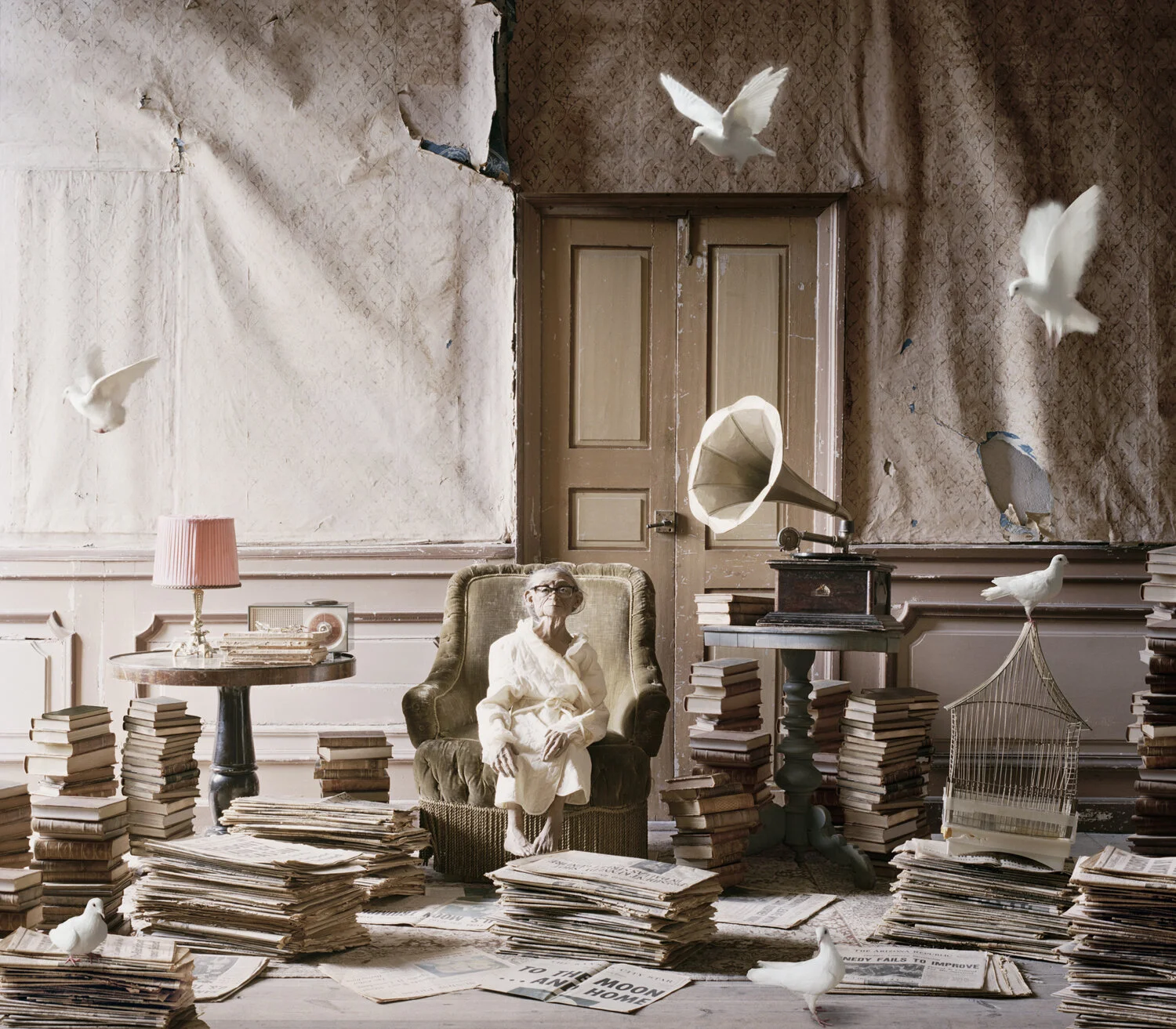

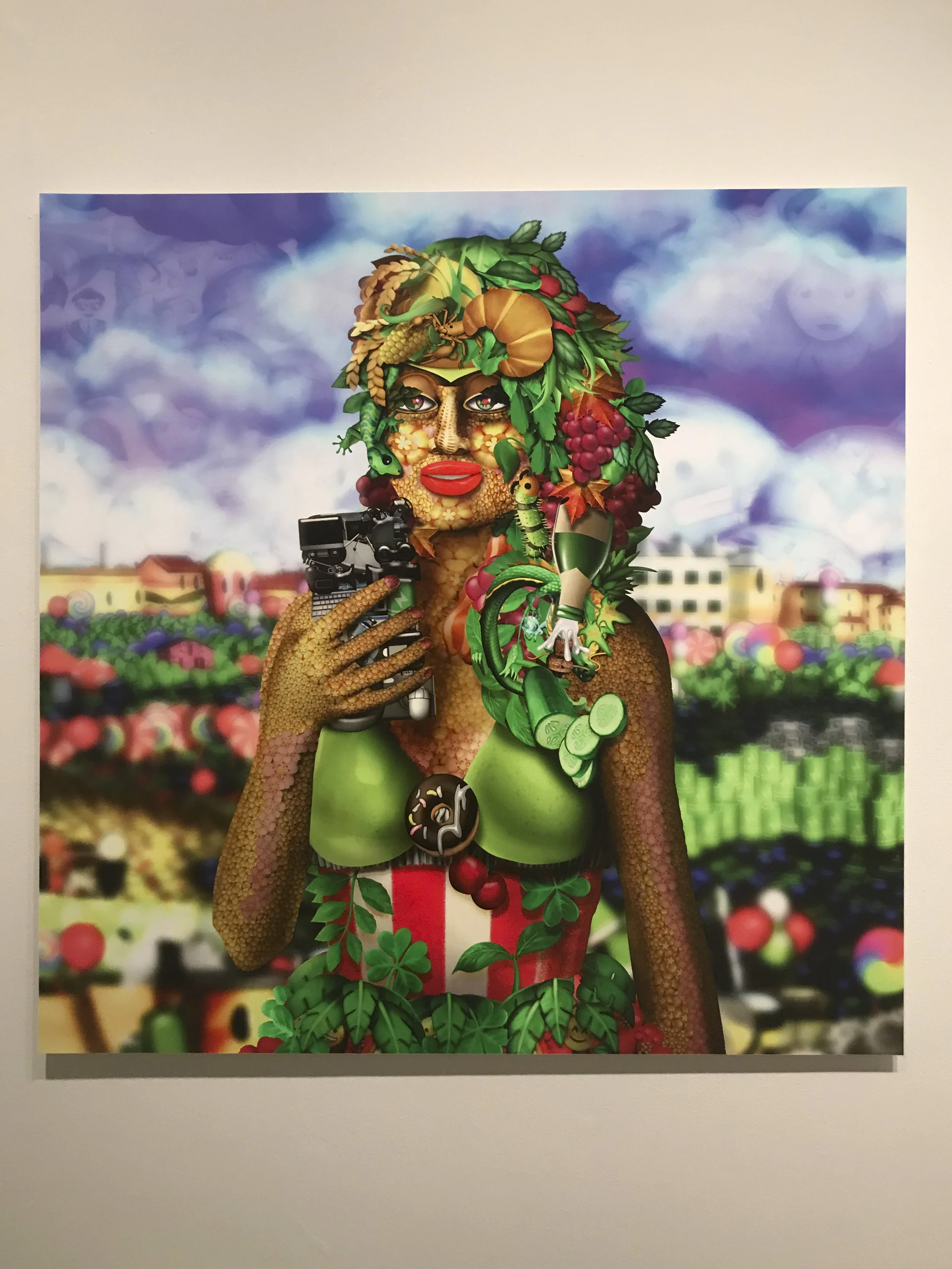

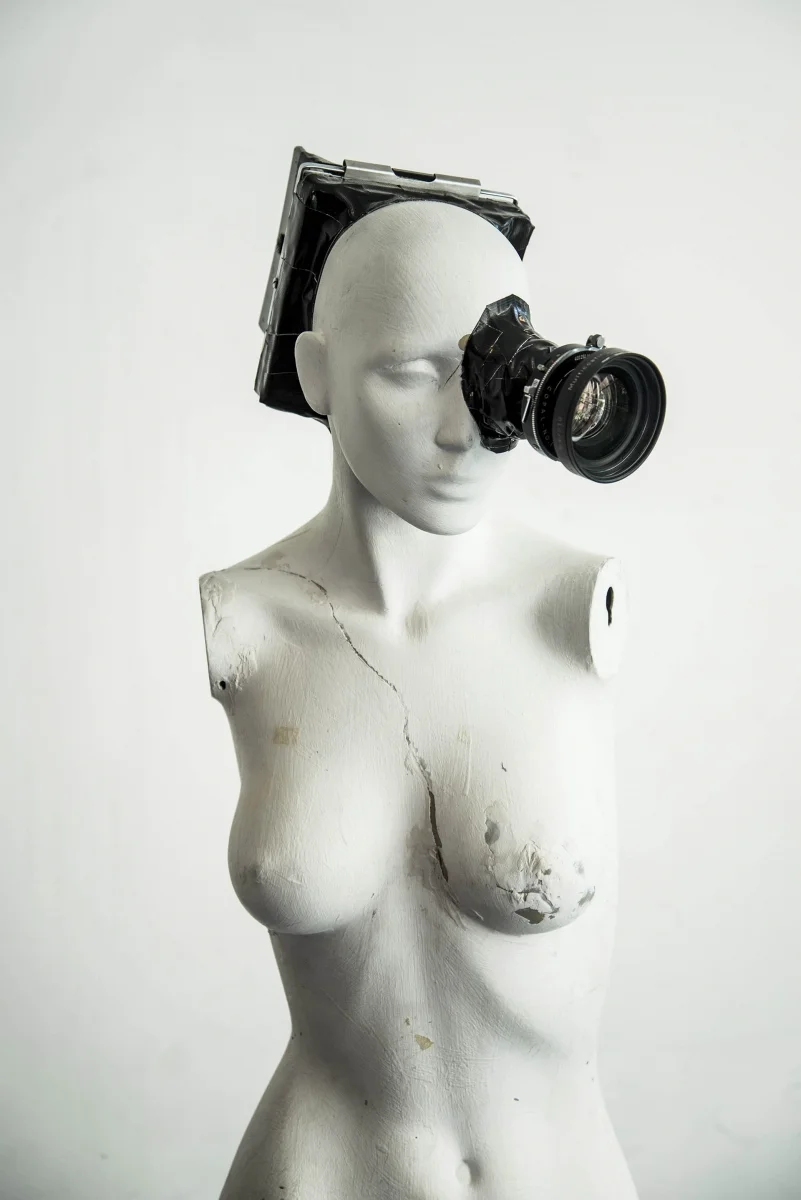

Last year when I reviewed Francesco Merlini’s work, my first glance reaction was something akin to what I feel walking into a class for reviews and seeing work created in this aesthetic pinned to the wall. “Ah crap, well, at least I refilled on coffee beforehand to get me through.” Merlini works with a contrast so tweaked, at times it looks solarized. Solarized!

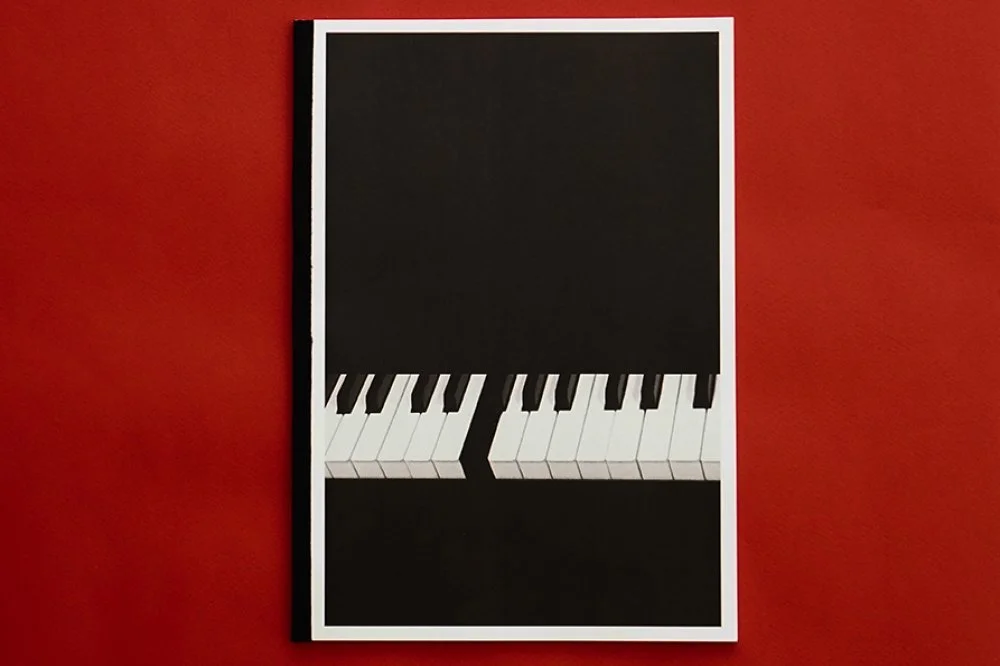

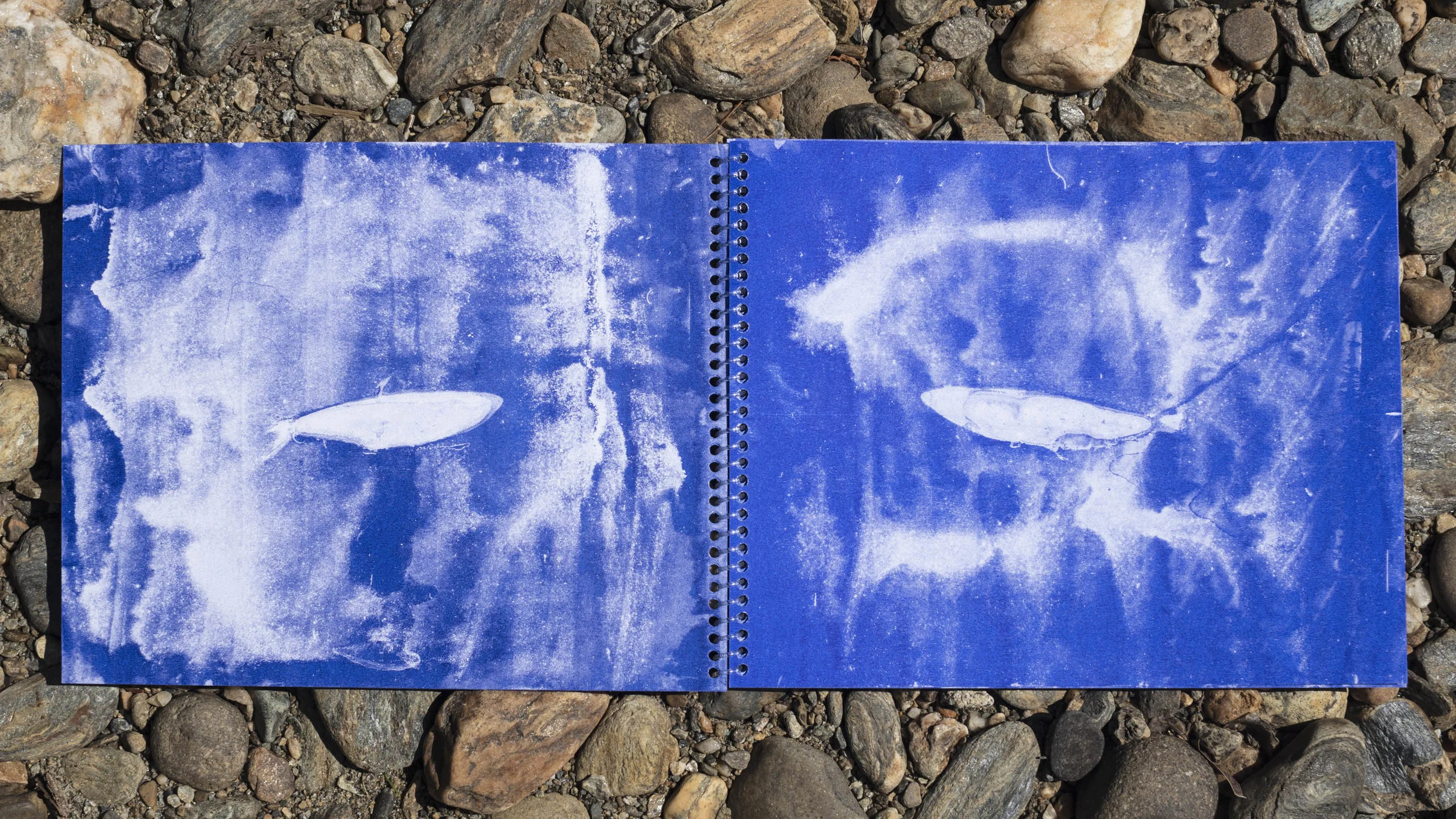

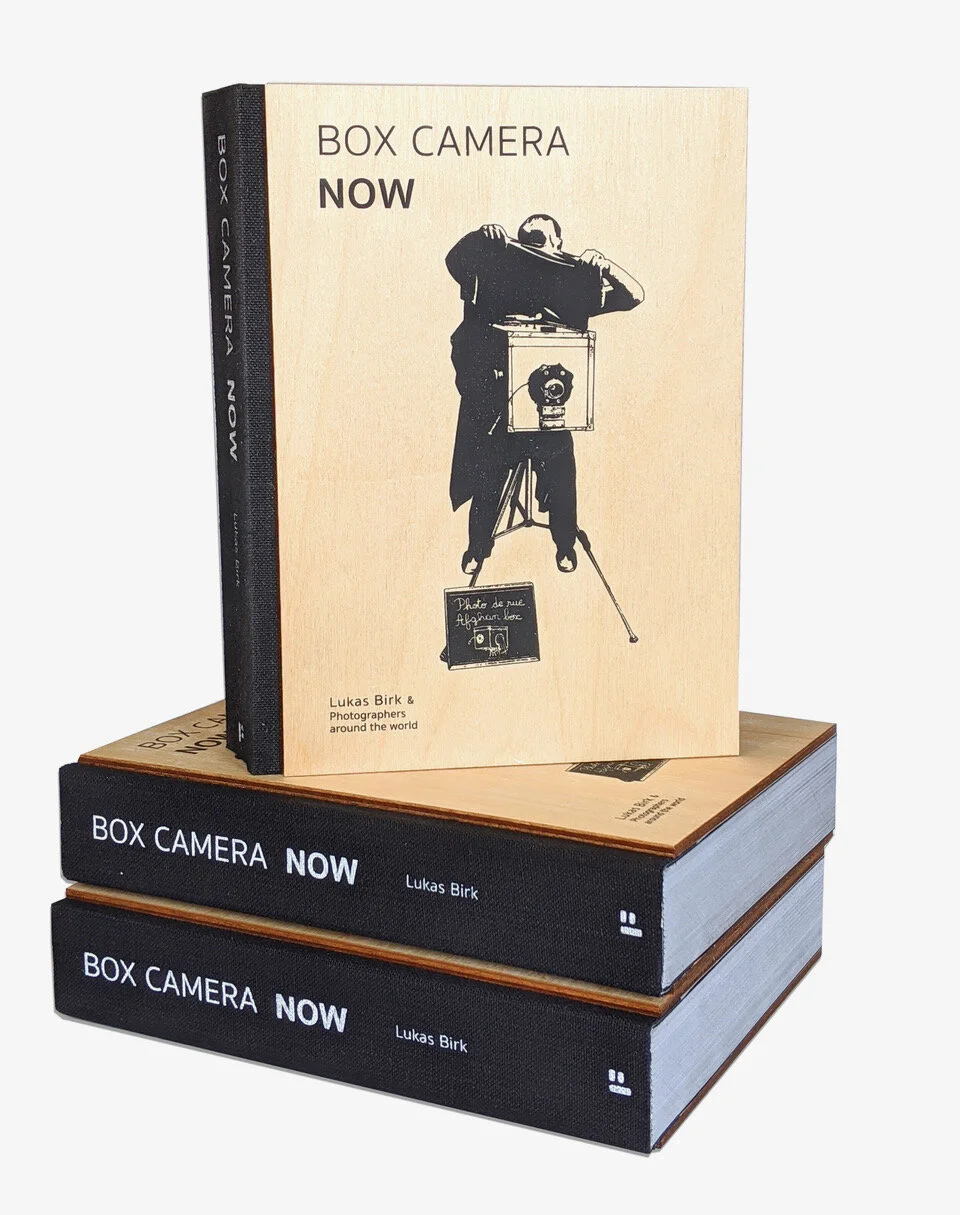

Yet, the more I looked at Merlini’s work, the more I discovered. I researched and interviewed him in order to learn more. He has revived a visual language by pushing it farther, drawing out textures, drying out the air inside the photographs to create a sense of crispness, creating work that hovers between the real and the surreal, photography and drawing, graphic art and fine art, 2D and 3D representation.

Merlini’s photographs reminds me that visually stereotyping is as lazy and problematic as any other form of stereotyping, and that our associations and expectations for an artistic style can be exploited and subverted by a photographer as talented as Merlini is as we continue to update, recycle, and cross-breed previous artistic languages in our search for a path forwards. Merlini also—thankfully—reminds me as a professor to provide patient support for students discovering this mode of working for themselves each semester. Who knows what they’ll be able to do with it.

—Tom Griggs

Untitled from the series Farang

Untitled from the series Farang

Untitled from the series Farang

Untitled from the series Farang

Untitled from the series Farang