Many people would agree that the family photo album is one of the most valuable possessions in a home. Tucked into bookshelves or kept in drawers and secret boxes, each is a family journal to be shared only with intimates and invited guests. These volumes are mythologized visual narratives that rarely include photographs of drunken embarrassments or the bruises on a child at the hand of a parent. Family secrets can be swept under the rug, but they never go away.

With his series The Hereditary Estate, Daniel Coburn has used photography to turn a light on his own family, one that has had a troubled past. According to Coburn, each of us inherit an “estate” from our ancestors, which includes not only photographs and physical possessions but also the symptoms of triumph and trauma. His familial discoveries have been revealing and at times troubling. It is because of this past that, for the last decade, Coburn has conducted research on why and how the construct of the idealized family came to be. Coburn is keenly aware of the ideal family archetype that was a key part of American advertising from the late 19th century to today. His photographs, some carefully staged and others open to chance, are a direct response and complete about-face to that idealized narrative. In his research, Coburn analyzed early Kodak advertisements, discovering that the company often presented examples of how to compose the ideal family. Coburn believes that this is part of the reason that he sees the same visual clichés so many of vintage family albums.

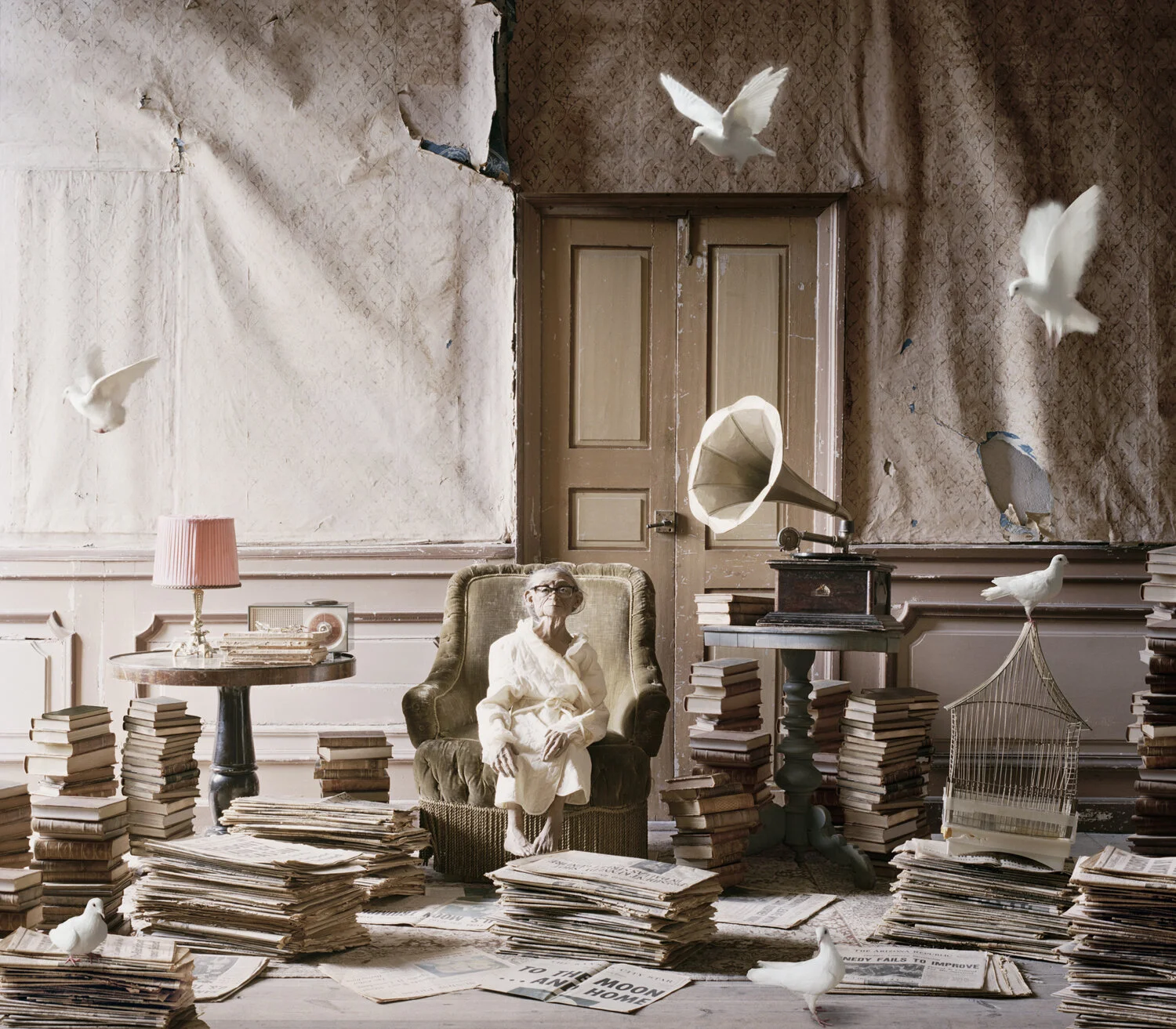

Resurrection

Coburn has written on and lectured extensively about his photography and his journey of using the camera to create his personal photographic tableaus. “I believe that photography is a problematic agent of truth. Most people ‘believe’ photographs because they are made with a machine. But, a photograph is a sentence taken out of context. Imagine having to choose only one line or word to represent your favorite novel or poem? The boundaries of the picture frame provide a powerful opportunity for the photographer to choose or edit what the viewer sees.”

As a child, Coburn’s mother suffered at the hands of her father. She received her first black eye by her father’s hand at the age of 11. In a recent, self-produced documentary about his family, Coburn’s father recounts the story of his brother’s suicide over a broken marriage—the pain of which lingers today. The uncle’s suicide happened before Coburn was even born, but affected him both directly and indirectly while growing up.

Untitled

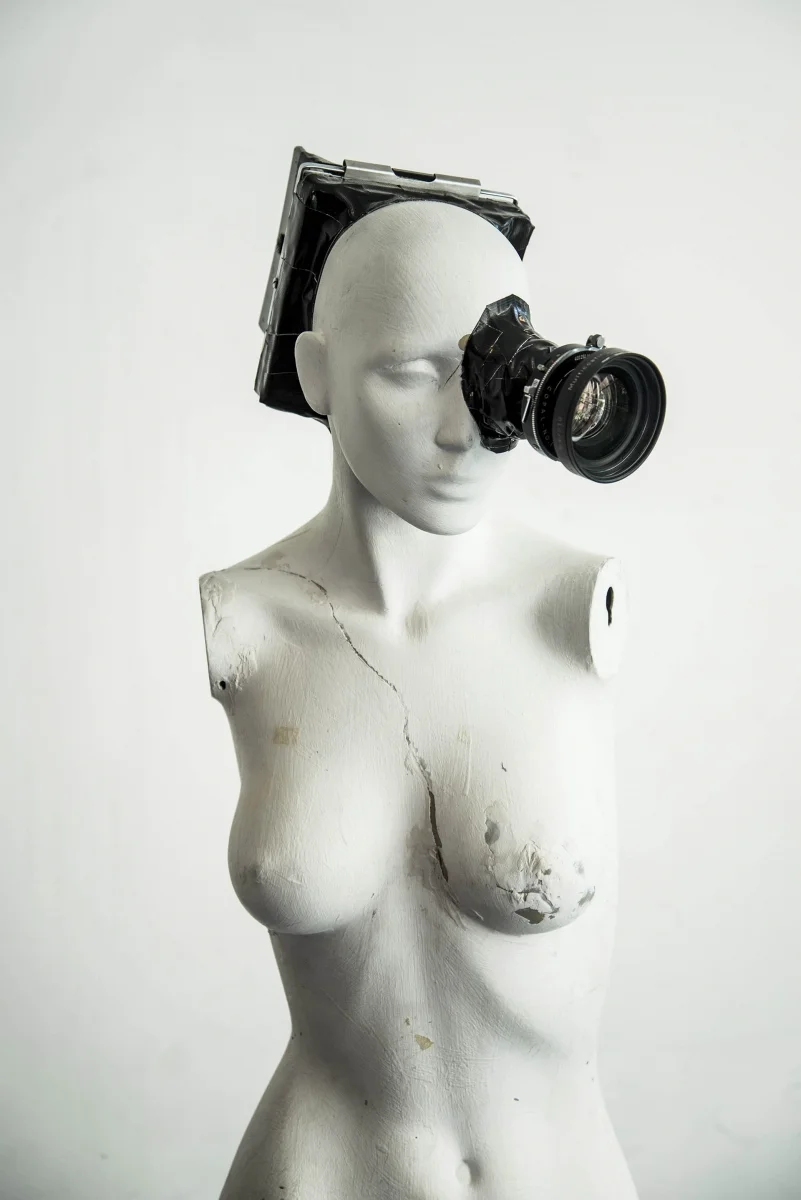

The Hereditary Estate grew from Coburn’s first project Next of Kin in 2012, a similar but color series of family photographs. This first deep exploration of his family was the foundation for his darker series to come. Where family memories fail him, Coburn fills in these gaps with found photographs—images lost to other families and adopted into his. Most of the anonymous images he finds are unsettling—a car wreck; a man holding a woman’s face from behind. Once added to Coburn’s mythology, these images are then cut, drawn on, rearranged, or digitally manipulated to serve as conduits for his personal journey in The Hereditary Estate. In the hands of a writer, novels are born from this kind of pain and darkness. But in Coburn’s pictures, The Hereditary Estate is a metaphorical self-portrait that gets deep inside the psyche of the photographer.

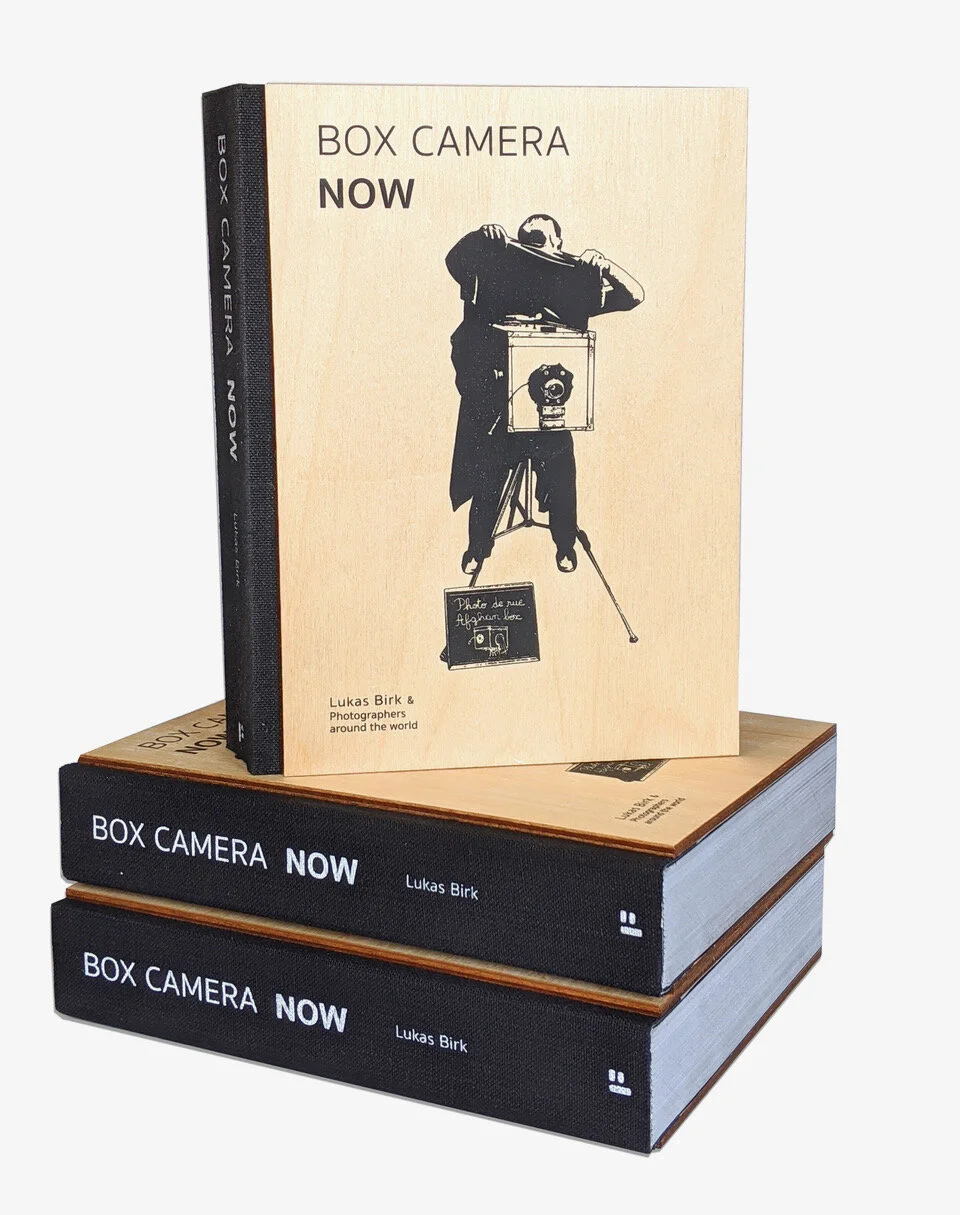

The Hereditary Estate has received significant critical praise and attention. Twenty-seventeen saw Coburn named as both a finalist for the prestigious Arnold Newman Prize for new Directions in Photographic Portraiture and a recipient of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship. The series was published as a book in 2014 by Kehrer-Verlag.

Lovers Embrace

The images Coburn presents are almost always staged, using imagery like beams of sun across the eyes of his mother or a ghostly white sheet blown across a bedroom. His parents are willing collaborators in this work. Their love manifests itself visually as a patient exchange between subject and photographer. When Coburn asked his father to gently wrap his hands around his mother’s face for the image “Lovers Embrace,” both parents cooperated in the assignment. The fact that Coburn’s family participated in his project so willingly made it into a healing exercise, and one of courage, trust, and patience.

This article first appeared in Issue 10.

John Foster is a contributor to Don’t Take Pictures, and has written for Design Observer, Raw Vision, Folk Art Messenger, Found Magazine, and others. He is a collector of outsider art and vintage photography. Portions of his extensive collection of found vintage photographs can be seen at accidentalmysteries.com