Every month an exclusive edition run of a photograph by an artist featured in Don't Take Pictures magazine is made available for sale. Each image is printed by the artist, signed, numbered, and priced below $200.

We believe in the power of affordable art, and we believe in helping artists sustain their careers. The artist receives the full amount of the sale.

We are pleased to release February's print, “Bartlettyarns, Harmony, Maine, 2010” from Christopher Payne. Read more about Payne’s work below.

Purchase this print from our print sale page.

Christopher Payne

Bartlettyarns, Harmony, Maine, 2010

Archival inkjet print

7 x 9, signed and numbered edition of 5

$150

Chris Payne understands space. Trained as an architect, he sees into the heart of a place—beyond its architectural features or utilitarian purpose. He is not ruminating on the hum of a mill when he photographs the last textile production houses in the U.S. Instead, he invites us to consider what makes those machines work and who drives their daily operation. While his photographs may remind us that industry and commerce clatter and clang in the background of our daily lives, they do not dwell on the din of production. Instead, these images illustrate a deeper purpose, reminding us of the lives that animate each loom, each room, and each space.

Payne graduated from Columbia and the University of Pennsylvania, intending to pursue life as an architect. As a young man, he worked in a National Park Service program that sent teams of historians, photographers, and architects to document disappearing industrial sites across America. As a member of one of these teams, he traveled to places as far flung as Alabama, Utah, Ohio, and New York, most notably Buffalo, where his team recorded the decaying architecture of a once-thriving industrial city. He remembers being struck by his colleagues’ photographs that captured the light and life of a place in a way that his architectural renderings, no matter how true or how sincere, could not fully achieve. As he says, “the photographers would transform the banal into something beautiful.” That experience, paired with a lifelong interest in adventure and, as he quips, “going places you’re not supposed to go,” were the seeds of his drift to photography.

After the architectural firm where he was working closed, Payne decided to pursue photography full time. His early project, Substations, secured him a reputation as an artist with the ability to transform the lost into the luminous, a trait that he amplifies even further in his recent series, Textiles. The series examines the final hold-outs of the American textile industry, documenting not only buildings and equipment, but the people and their surprising vibrancy.

Wool Carding, S&D Spinning Mill, Millbury, MA, 2012

Payne has traveled up and down the east coast locating mills, following rural roads and sometimes secretive leads. Some mill owners are more accommodating than others, but Payne’s passion undoubtedly breaks down most barriers. It’s a sincere passion, one built on an appreciation for the difficult relationship between working-class people and industrial history. Indeed, he calls his work “patriotic” because it makes visible groups of people and their work that linger on the margins of popular history despite being central to the country’s growth. Payne’s photographs illustrate, then, not just the magnificent complexity of industrial factories and machinery, but the impossibly complex relationship between person, place, and machine.

Among the most important of the images is “Wool Carding, S&D Spinning Mill, Millbury, MA, 2012.” In this image, the vibrancy of color immediately demands attention. Magenta fibers sing through machinery and collect in tufts on surrounding joints and gating. The power of the color, however, is only the introduction. The depth of field—color extending far back into the machinery in all directions and across rooms, forming chambers of light—illustrates both the volume of work being done and the impressive scale of industry to support it. The color, in other words, invites us into a story about the production, about the lives creating or demanding it, the economy funding it, and its destination. Being struck by the startling magenta here is the same as being struck by the need for such vibrant color in our lives. To make sense of it, we must make sense of our own yearning for that color.

Raw Dyed Wool Before Carding, S&D Spinning Mill, Millbury, MA, 2012

So it is also with the red heaps on the floor of the dark, crumbling room in “Raw Dyed Wool Before Carding, S&D Spinning Mill, Millbury, MA, 2012.” The contrast between the soft, if dense, clouds of red and the angled, chipped greens of the walls create a strangely inviting scene, where past and present jockey for attention. The glowing light of the windows provide a luminescence, but the pile of production residue holds its power because it suggests vitality in a scene that would otherwise be entirely destitute of life and energy. The old space, framed with deteriorating mortar and crowned with timber, still lives, a vibrant heart in an old body.

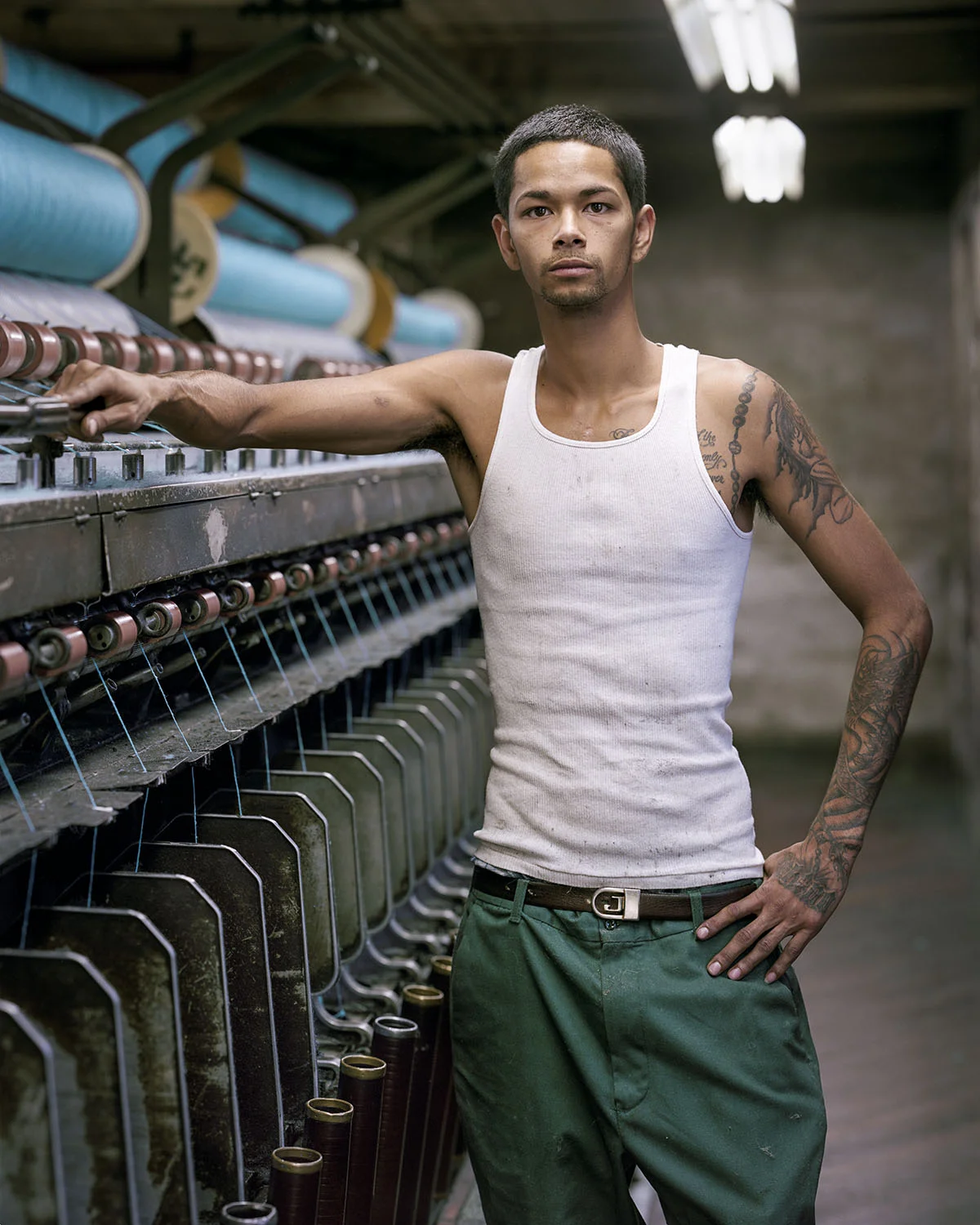

Payne’s use of color, however, is only one of many aspects of his work that demonstrates the vibrancy of these mills. In some images, the glistening perfection of machinery takes center stage. Photographs of the sheen of sometimes single fibers strung out from steel and brass suggest the delicacy of an operation that must surely seem, when taken as a whole, monstrous. At other times, Payne turns his camera toward those who work the mills. Among those images is the striking portrait of Junior, whose tattoos and intense stare create an odd tension between the present and the past. The idea of “millworker” likely does not typically conjure images of men like Junior, yet he stands there, right arm resting on a machine that has undoubtedly spun out line and textile since long before he was born. His slender body contrasts with the hulking force of the machine, but he is nothing if not certain of his presence.

Payne continues to seek out America’s increasingly rare textile mills. One senses an urgency when he discusses his trips to the mills, even an intense longing. He recognizes that he is documenting a past that is slipping by, and if anything, we see in his work not so much an attempt to record that past for us, but a desire to breathe life into it.

Junior, S&D Spinning Mill, Millbury, MA, 2012

Roger Thompson is Senior Editor for Don’t Take Pictures. His features have appeared in The Atlantic.com, Quartz, Raw Vision, The Outsider, and many others. He currently resides on Long Island, NY, where he is a professor at Stony Brook University.

This article first appeared in Issue 7.