Those who read enough photo history may be tempted to believe two things: first, that the invention of the Kodak in 1888 was the most influential thing to ever happen in the medium; and second, if the Kodak isn’t the catalyst for a particular aesthetic or conceptual change in the field, Alfred Stieglitz is. Though I recognize their importance in the history of photography, I’ve always been skeptical about this absolute confidence in both the machine and the man. So in researching the rise (and fall) of photography groups—like the 19th century’s Linked Ring, the 20th century’s Photo-Secession, and Group f/64 in the 1930s—I was suspicious when the appearance of the Kodak and the genius of Stieglitz were identified in the literature as the only stimuli for this activity.

Frank Eugene, Portrait of Alfred Stieglitz, 1901. Photogravure.

Though some organizations date to before the late 19th century or after the mid-20th century, the heyday of the photography club/group was from the 1890s to the 1940s. In his foreword to Photo-Secession: Photography as a Fine Art, famed photo historian Beaumont Newhall states, “From the beginning, photography’s position in the art world has been a challenge.”[i] Newhall quickly lays the foundation from which all photography groups were built: promoting the medium’s position as a fine art. Yet, if Newhall’s statement is true, why were these groups concentrated in a 50-year span? Why didn’t they appear earlier and last longer? The answer is found, not only in the importance of Kodak and Stieglitz, but in the complex presentation and use of photography in those years, a social framework that echoes through our own digital age.

The mid- to late-nineteenth century saw a dramatic increase in practicing photographers as a rising leisure class explored options for filling their non-working hours. Theaters, dances, and other entertainments grew in number and frequency as did book clubs, outing clubs, and bicycle clubs. Along with leisure time, theories emerged on how it should be spent. Ideas about “self-culture” were plentiful. Like today’s self-improvement philosophies, self-culture advocated for personal development and rejuvenation through healthy or useful hobbies. Enjoying a popular resurgence, Benjamin Franklin’s concept of “useful knowledge” advocated for practicality and direct experience. Within this framework, leisure was meant to be both relaxing and productive. The practice of photography fit easily into this concept of beneficial leisure activities. In fact, the Kodak reinforced it.

Kodak Advertisement in National Sportsman Magazine, 1908

George Eastman’s No. 1 Kodak was released in late July 1888. Elizabeth Brayer’s oft-cited text, the first biography of Eastman, perhaps says it best: the Kodak, “set the world to snapping pictures.”[ii]2 What was most notable about the Kodak was that it removed both the burden of chemistry for the production of prints and negatives and the mathematics required to calculate the relationship between time, distance, and light. In short, it eliminated labor from the practice of photography, making it a leisure activity. Moreover, to appeal to the cult of self-culture, the company’s advertisements emphasized the benefits of photography as a pastime.

It is no surprise then, that the art photography movement, known as pictorialism, is generally believed to have begun in 1888, the same year as Kodak’s release. Formed in that year, the Photo-Club de Paris—with members including Robert Demachy and Émile Constant Puyo—was dedicated to creating photographs explicitly artistic in intention.[iii]3 The movement toward this type of photography was truly international, with clubs appearing in most major cities over the next 15 years.

Though the Kodak may have spurred the birth of these groups, they remained inchoate until 1893. That year saw the rise of specialized exhibitions, also called salons, signaling the full maturation of the movement. The photographic salon was the most significant aspect of the pictorial movement.[iv] Alfred Maskell, who founded the Brotherhood of the Linked Ring in 1892, emphasized, “the matter of exhibitions,” as the most important activity of the club. Exhibitions legitimized photography, launching the medium into the realm of the fine arts.

Robert Demachy, Study in Red, 1898

Not surprisingly, an immense exhibition—the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, known as the White City—spurred the rise of the photography club exhibition. Though photos were perhaps the most visible objects at the fair (one visitor described the White City as “almost a photographic exhibition”[v]), photography was not treated as an art form. The medium was excluded from exhibition in the Fine Arts building, and was instead presented with “Instruments of precision, experiment, research.” Additionally, within that exhibit, the chief of the Bureau of Liberal Arts, Selim H. Peabody, called for, “No attempt at classification, separating portraits, landscapes, etc., … No prizes, in the usual sense,”[vi] thus eliminating the possibility for genre divisions and connoisseurship, two pillars of fine art.

Outside of the White City, the growing community of art photographers reacted against this dismissive treatment. Exposition juror Catherine Weed Ward lamented, “There is so much poor work done, technically and artistically … that the general judgment as to the work of all is greatly affected, and photography … is often forced into a lower place than is its just due.”[vii] While prior to 1893 only one exhibition devoted solely to art photography was held, following the World’s Fair’s disastrous presentation, photography exhibitions began in earnest. Only months after the fair, the Brotherhood of the Linked Ring curated a photography salon (mimicking painting salons) with a juried selection, careful hanging, and work separated by genre. A contemporary report praised the effort: “We must admit that the promoters have done remarkably well … getting together what is, on the whole, an undoubtedly fine collection of pictures.”[viii] The Hamburg International Exhibition of Photography was even more successful. Featuring over 6,000 photographs from photographers throughout the world, the exhibition was enormously popular and was seen by more than 13,000 visitors in 51 days in late 1893. Soon afterward, salons appeared in Berlin, Munich, Glasgow, and Turin. In America in 1896, the Camera Club of the Capital Bicycle Club of Washington held its own successful photographic exhibition. The Director of the United States National Museum (now known as the National Museum of Natural History) was so impressed by the photography displayed that he purchased 50 prints for $300 for the national collection. It is the first known museum purchase of art photographs in the United States.

Charles Arnold, Court of Honor at the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893

Oddly, it is this success—the institutionalization of art photography—that led to the decline of photography clubs. The proclamation of photography as an art was eventually proved by its presence in institutions. As photography moved into universities and museums, new advocates for the medium emerged; academics and curators took up the cause of promotion. Club members were free to create their art without having to justify it as such. Instead, they could turn their efforts to expanding the aesthetic scope of art photography.

Group f/64—which included Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, Brett Weston, Edward Weston, among others—did not claim that the pictorialist photos that came before them were not art. Rather the group advocated that the manipulation of negatives and prints and the construction of a subjective composition for which the pictorialists were known were not the only characteristics of a fine art photograph. f/64 looked to expand the definition of art photography to include a straight, or direct aesthetic obtained through purely photographic methods. Notably, the group announced their formation via a museum exhibition held in 1932 at the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco, thus utilizing the institution to reify their point of view.

Heidi Kirkpatrick, Tree Fern, 2015. Cyanotype.

By the 1980s, photography clubs had all but disappeared as the medium found strong footing in institutions. Photo historian Douglas Nickel noted, “the decade witnessed endowed chairs and university courses … increasing numbers of doctoral students gravitating toward study in the area, the widening popularity of photographic activities within museums and the book trade,” and perhaps the most notable aspect of photography’s secure place as an art form, “a voracious new collecting market.”[ix]

Though it seems to be a remnant of photo history, the rise and fall of photography clubs is a lesson for our digital age. While Kodak photography was promoted for leisure, by definition a secondary activity, digital photography has become a primary part of life. Entire industries and careers are based on this new mode of photography, which has simultaneously become a method of communication and instrument of knowledge. Its sheer ubiquity has once again raised questions about the nature of art photography and its uniqueness as a medium. In the museum, photography departments are being absorbed into general “works on paper” departments, or into “modern” or “contemporary” departments. Photography is slowly losing its place as a singular course of study in the university as less tenure-track positions are filled and general courses are offered in lieu of specialized topics.[x] As art institutions absorb the medium into general courses and large museum departments, photographs are no longer recognized for their incredible singularity of both process and product. Photography has gained its place in the fine arts, only to lose some of its uniqueness.

Priya Kambli, Meena Atya and Me, 2012

Photographers, in turn, seem to recognize this loss of idiosyncrasy. Many have turned to processes or products that are uniquely photographic in nature, creating work that embraces ontological aspects of the medium. Photographers are rehearsing pictorialist attitudes—embracing film or alternate processes, hand-manipulating their photographs, or staging subjective compositions. Others are creating projects that interact with photo history or archival images, emphasizing a legacy within this singular medium. Photography groups are again emerging online, promoting their activities and aesthetics through digital exhibitions. The result of this increased activity remains to be seen. But as a note to future historians, all of this is activity is progressing without a ubiquitous machine like a Kodak, or a prominent man like Stieglitz anywhere in the picture.

Lisa Volpe is the Associate Curator of Photography at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts.

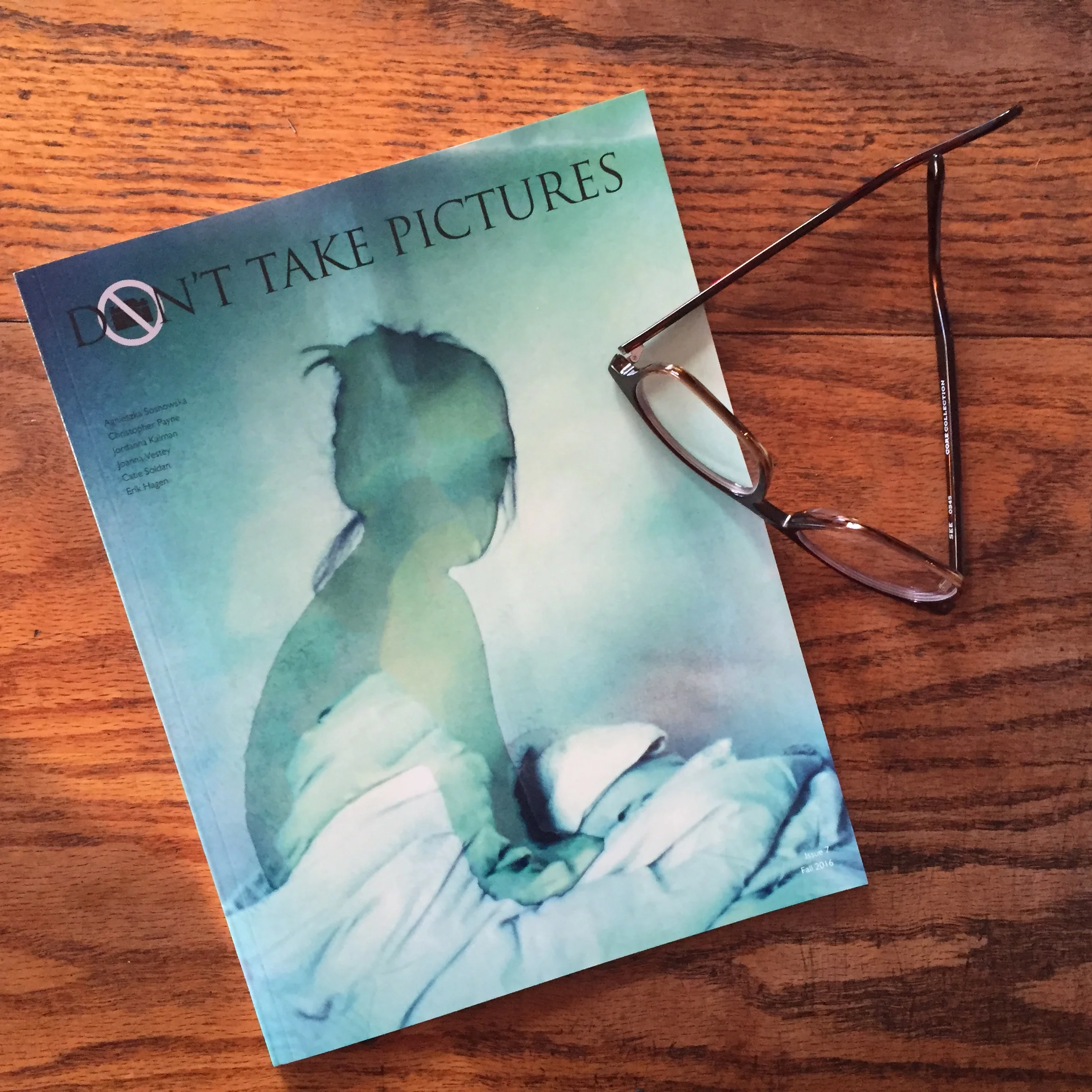

This article first appeared in Issue 7.

[i] Beaumont Newhall, “Foreword,” in Photo-Secession: Photography as a Fine Art (Rochester, NY: George Eastman House, 1960), 3.

[ii] Elizabeth Brayer, George Eastman: A Biography, annotated edition (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2006), ix.

[iii] For an excellent summary of the history of ‘art’ photography, see James Borcoman, “Purism Versus Pictorialism: The 135 Years War. Some Notes On Photographic Aesthetics,” ArtsCanada nos. 192–195 (December 1974), 68–82.

[iv] J.T. Keiley, “The Linked Ring,” Camera Notes, vol. 5 (1901), 111–120.

[v] Quoted in Alan Trachtenberg, The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age (New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 1982), 230.

[vi] The American Amateur Photographer, vol. V, January to December (New York, NY: The Outing Company Limited, 1893), 134.

[vii] Ibid., 63.

[viii] Walter Welford, ed., “Functions of the Month,” The Photographic Review of Reviews III, no. 23 (November 15, 1893), 362–363.

[ix] Douglas R. Nickel, “History of Photography: The State of Research,” The Art Bulletin 83, no. 3 (September 1, 2001), 548.

[x] Jordan Weissman, “The Ever-Shrinking Role of Tenured College Professors (in 1 Chart),” The Atlantic, Accessed May 18, 2016, http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2013/04/theever-shrinking-role-of-tenured-college-professors-in-1-chart/274849/.