A review of the New York Art Book Fair is inevitably an exercise in exclusion. One can’t possibly see or discuss everyone. Run each year by the inventive folks at Printed Matter and hosted by MoMA PS1, the fair overflows with such a wide range of expression that the best any single person can do while visiting it (let alone reviewing it) is to enjoy one’s favorites with the recognition that you likely missed lots of other favorites that the crowds or time prevented you from discovering. That’s a quick qualification to mean this: the NYABF is fun, exciting, and impossible to summarize or document, so all I’m going to do is talk about a couple of folks I couldn’t resist.

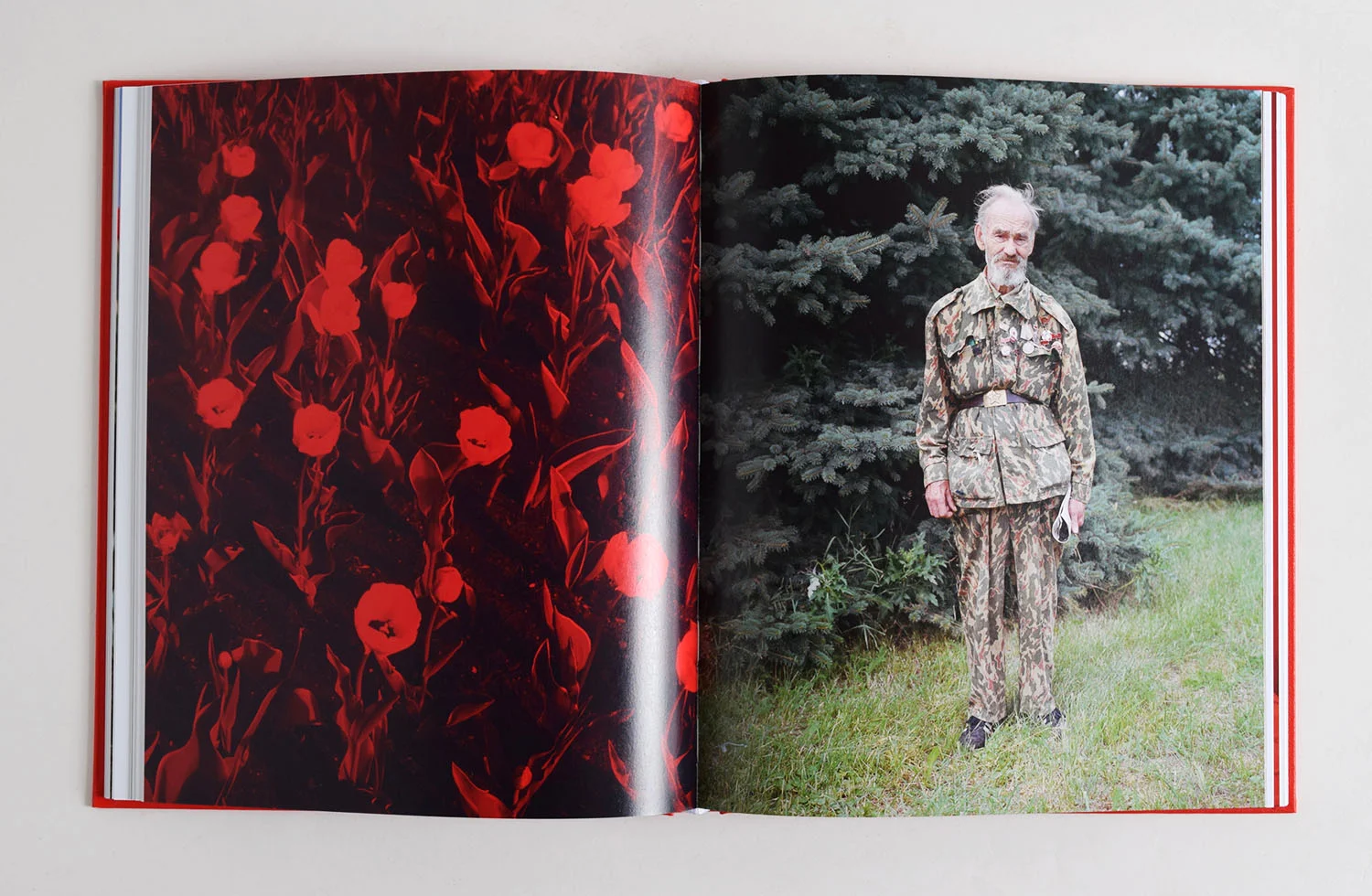

Among the more daring photographers exhibiting his work was Andrew Miksys. Miksys’ most recent book, Tulips, is a beautifully printed hard cover volume from his time in Minsk. While images of tulips appear on various pages, loosely unifying the collection, the most stunning photographs are the portraits. Some are tonal—shot in color that, on one hand, highlights the figure while, on the other hand, washing it with reds, greens, and blues to make it less defined, even if more vibrant. Others are essentially studies of a person in a domicile: an old woman sits in front a safe decorated with plants and a balloon, a young man poses in front of a Nazi flag, and old man in fatigues stands slightly sideways in a field. They are ruminations on types and contrasts with the tonal images, many of which are nudes. The book is alluring, and the printing beautiful.

Tulips by Andrew Miksys

Kris Graves’ The Testament Project has similar manipulation of color, but whereas Miksys’ work seems to reflect on place, Graves’ work seems to reflect on identity. The two volumes Graves had available from The Testament Project (the third is a video installation) collect portraits of African Americans—one volume women, one men—photographed under colored lighting. Graves gave his subjects the opportunity to choose a color in which to be photographed, so each image represents a choice by the subject for how to be viewed. Graves is rather clearly challenging notions of race and color, but the importance of the work is in its conscientious and intentional attempt to provide subjects agency in the process of representation. While the photographer, in this instance, is still clearly making an image, he is constrained by a subject’s choice about what may be the most fundamental aspect of photography itself—lighting. The images glow, not just with color, but with certainty and confidence, and they suggest a person who challenges notions not only of race, but representation and power. Graves' more recent book, Provisional Scenery, moves away from the figure. Largely landscapes, most of which rely on the use of line to disrupt natural space, the interiors are especially compelling. I get the sense that Graves understands inner spaces, and all three works are testament to a nuanced view of the individual’s place in the world.

The Testament Project by Kris Graves

Other work is, of course, worthy of attention. Cesura, a collective of Italian photographers, was back with their wide-ranging, purpose-driven work. I wrote about them last year, and my mind hasn’t changed. Gary Kachadourian, a Baltimore photographer working in Tulsa, was the most notable of artists who dealt with the former oil capitol of the world—and there were a surprising number of Tulsa sightings—book titles, image names, artists working in, and people just wearing Tulsa shirts. I can’t explain it, but it perhaps validates the The New York Times’ claim a few years ago that Tulsa was a mecca for artists. It certainly has the right cost of living. The arrival of some big-name galleries to the NYABF was a bit startling. I’m not sure why Gagosian was there (offering tattoos no less), nor am I sure why they commandeered such a large space, but I take it to be a rather tacit admission of the importance of the fair and the savvy of the curators. I think it a good sign for the health of the fair—not because of the cost of a booth, but because when larger players show up, it suggests that someone somewhere had a little idea that has grown into something formidable. That is surely a sign of hope for all artists, and the only thing we as visitors and patrons can all hope for is that the fair doesn’t lose its close-knit, frenzied feel as it continues to make its mark. One can also hope, I suppose, that it will remain free to attend.

Roger Thompson is the Senior Editor for Don’t Take Pictures. His critical writings have appeared in exhibition catalogues and he has written extensively on self-taught artists with features in Raw Vision and The Outsider. He currently resides in Long Island, New York and is a Professor at Stony Brook University.