For 18 years I have kept a box underneath my bed. It holds letters and objects and tokens of memory that I consider significant. Made from now-crumbling cardboard, the box itself is perfectly ordinary. Over the years its contents have been purged and built up again as I moved my tangible history into different homes in different states. Many people have similar boxes with similar contents. For Lori Vrba, an artist whose work is autobiographical, the metaphorical “box underneath the bed” became an intimate series of photo-based assemblage pieces.

Anastasia

After moving from Texas to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, Vrba began to examine her life—past and present—through the lens of a camera. During this time she was busy caring for her children and exploring the lush Carolina surroundings. Her sepia toned photographs are rich and earthy, and her children appear like woodland sprites—floating in streams, peeking from behind trees, and holding carefully arranged flower petals on their outstretched palms. While her children are often present in her photographs, she sees them as vehicles through which she tells her own story. Her children, she says, “are characters in my play. And my story is a long languid Southern tale of blood kin, chosen family and kicked-to-the-curb-don’t-come-around-here-no-more types. It’s just the truth of me.”

While developing her series Drunken Poet’s Dream, Vrba began to consider her photographs as having a life beyond their two-dimensional existence. In that series, she used her own images as a backdrop, laying objects directly onto the prints and re-photographing the resulting fantastical scene. Combining photographs with three-dimensional objects was thrilling, and she soon moved out of the darkroom and into the woodshop, incorporating her images into boxes that stood as their own art pieces. Despite her affinity for assemblage, Vrba identifies solely as a photographic artist. Every assemblage piece holds at least one of her original images. Though they are often manipulated, the prints are the central component around which the rest of the sculpture grows.

Specimen

In these boxes, Vrba tells an enigmatic story of her life using found objects—feathers, discarded dolls’ hands, letters, and other curios—arranging them into aesthetically pleasing displays. These pieces are exhibited alongside her equally personal black and white photographs. As a photographer, Vrba takes pride in the analogue process, methodically printing and toning her images by hand. Each photograph’s narrative informs all other aesthetic decisions for her assemblage work. From there, she considers how to combine various elements to tell the story, how to arrange them so that the eye is stimulated but not overwhelmed, and how to use the right tools to achieve the desired aesthetic. The photographs she includes are often cut up or collaged versions from other series. Vrba enjoys “giving them new life,” believing that, “they get to participate in a new conversation and tell a new story.” She personifies each piece stating, “I respect what and who they’ve been up to that point, but I firmly believe that if I could just ask them if they’d like to be a part of something else, they would all jump up and down with hands raised, ‘Pick me, pick me!’”

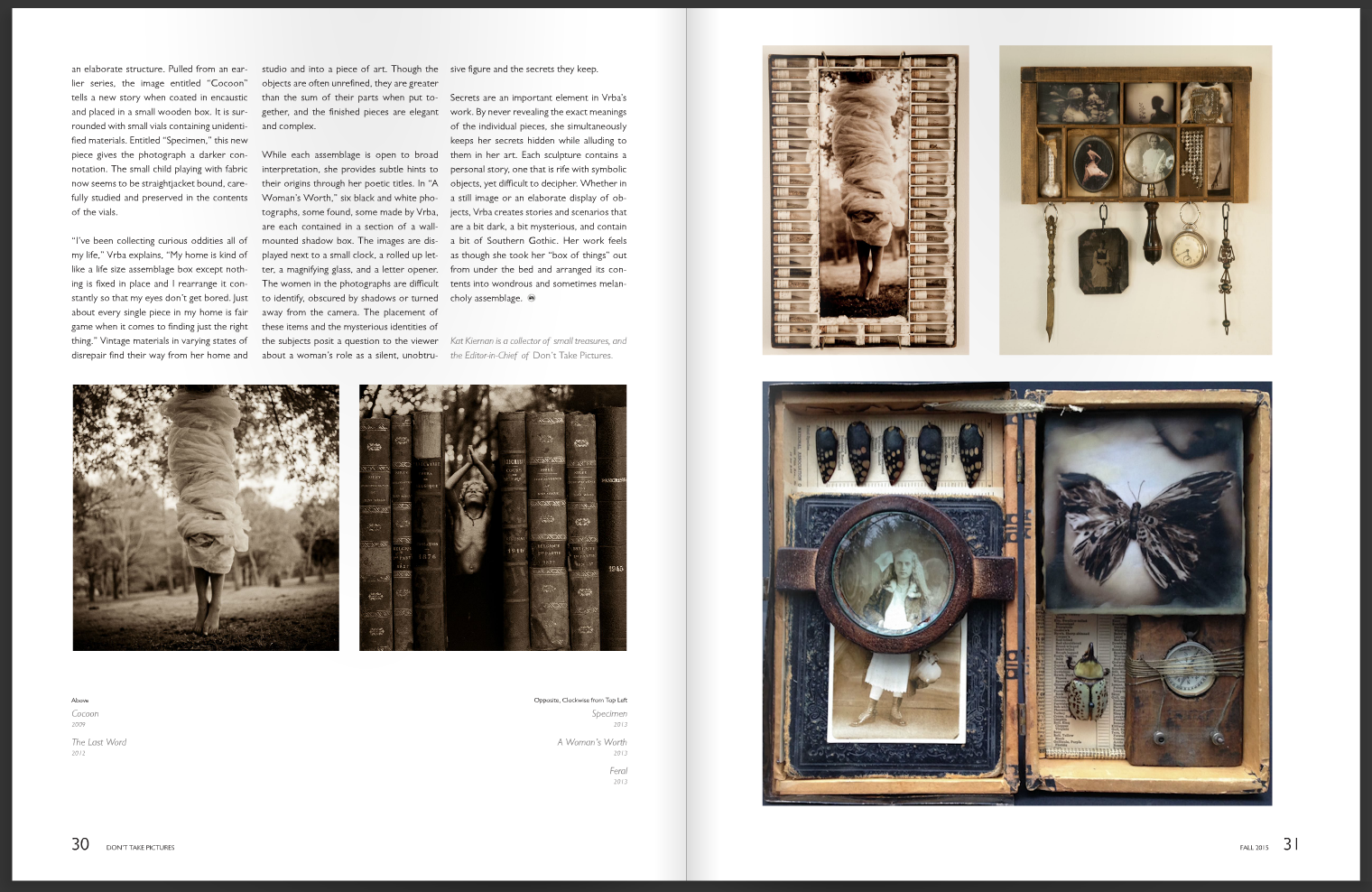

The photographs she ultimately chooses find themselves in strange places. Covered in feathers, distorted by magnifying glasses, hidden behind doors, and trapped inside a snow globe; each one, the centerpiece of an elaborate structure. Pulled from an earlier series, the image entitled “Cocoon” tells a new story when coated in encaustic and placed in a small wooden box. It is surrounded with small vials containing unidentified materials. Entitled “Specimen,” this new piece gives the photograph a darker connotation. The small child playing with fabric now seems to be straightjacket bound, carefully studied and preserved in the contents of the vials.

A Woman's Worth

“I’ve been collecting curious oddities all of my life,” Vrba explains, “My home is kind of like a life size assemblage box except nothing is fixed in place and I rearrange it constantly so that my eyes don’t get bored. Just about every single piece in my home is fair game when it comes to finding just the right thing.” Vintage materials in varying states of disrepair find their way from her home and studio and into a piece of art. Though the objects are often unrefined, they are greater than the sum of their parts when put together, and the finished pieces are elegant and complex.

While each assemblage is open to broad interpretation, she provides subtle hints to their origins through her poetic titles. In “A Woman’s Worth,” six black and white photographs, some found, some made by Vrba, are each contained in a section of a wall-mounted shadow box. The images are displayed next to a small clock, a rolled up letter, a magnifying glass, and a letter opener. The women in the photographs are difficult to identify, obscured by shadows or turned away from the camera. The placement of these items and the mysterious identities of the subjects posit a question to the viewer about a woman’s role as a silent, unobtrusive figure and the secrets they keep.

Secrets are an important element in Vrba’s work. By never revealing the exact meanings of the individual pieces, she simultaneously keeps her secrets hidden while alluding to them in her art. Each sculpture contains a personal story, one that is rife with symbolic objects, yet difficult to decipher. Whether in a still image or an elaborate display of objects, Vrba creates stories and scenarios that are a bit dark, a bit mysterious, and contain a bit of Southern Gothic. Her work feels as though she took her “box of things” out from under the bed and arranged its contents into wondrous and sometimes melancholy assemblage.

This article first appeared in Issue 5.

Kat Kiernan is a collector of small treasures, and the Editor-in-Chief of Don’t Take Pictures.