In an era where digital technology has allowed photography to grow in both scale and precision, photographers might question the relevance of photorealistic painting. If an artist intends to record a scene or person in the most lifelike manner, why not use a camera instead of a brush? Until recently, photography was not considered a part of the fine art world. Even today, it is often segregated from other mediums in museums and galleries. Too often, the labels of artist and photographer are perceived as mutually exclusive. While it is not uncommon for photography to be influenced by other mediums, I set out to explore situations where photographs serve as an integral component to more traditional arts. I sat down with Louis K. Meisel, the world’s foremost authority on photorealism, to discuss photography’s relationship and influence on the movement.

Louis K. Meisel

I arrived at Meisel’s SoHo gallery on a rainy Monday morning. Unlike many New York City galleries, he keeps the atmosphere decidedly casual. “It’s supposed to be casual, it’s supposed to be fun, and it’s supposed to be about the art. I don’t want any arrogance here.” A widely respected collector and art dealer, his unpretentious attitude and obvious excitement about his artists is refreshing and unexpected.

Meisel coined the term “photorealism” in 1969, and the art world was forever changed. Defined as artists who use the camera to gather information and then employ mechanical or semi-mechanical methods to recreate the image on canvas, they possess the technical skills to make their paintings appear photographic. Coming off the heels of the abstract expressionists, this movement was still new and undefined in the late 1960s. Meisel began to assemble a school of artists who “were thinking the same way or had come across the same questions or answers independently.” For these artists, the camera was as important to their craft as the paint on their canvases.

Chanel, Audrey Flack. Courtesy of Louis K. Meisel Gallery

Almost since the invention of photography, painters have been referencing photographs. The camera obscura and camera lucida were common tools of the trade, but few traditional artists acknowledged their use. Photorealists not only admit to using photography to inform their paintings, but take pride in their photographic skills. “Many of them are extraordinary photographers.” Meisel says, “They’re scientists, they’re technicians.” He makes a comparison to the impressionists, who sketched in the field before returning to the studio to paint. Similarly, the photorealists go out into the world and make photographs before they create a painting. He says, “[The photorealists] were saying they used the camera, they’re proud of it and it helps them greatly. They make thousands of photographs to make one painting because the camera doesn’t reach all the way down the street, or focus on everything at once, and you need a telephoto lens to get details on a building. So they use a lot of photographs.” Meisel uses a painting by Audrey Flack as an example. She set up a still life of her vanity table and photographed it, then projected the image onto her canvas and rendered the painting. What distinguishes this work from realism is that without the camera, these paintings could not exist. Meisel leads me to a piece by Tom Blackwell, who is best known for his paintings of motorcycles. “You couldn’t do a motorcycle covered with chrome before the camera. You could get close, but not the same. Not photorealism.”

Red Lightning, Tom Blackwell. Courtesy of Louis K. Meisel Gallery

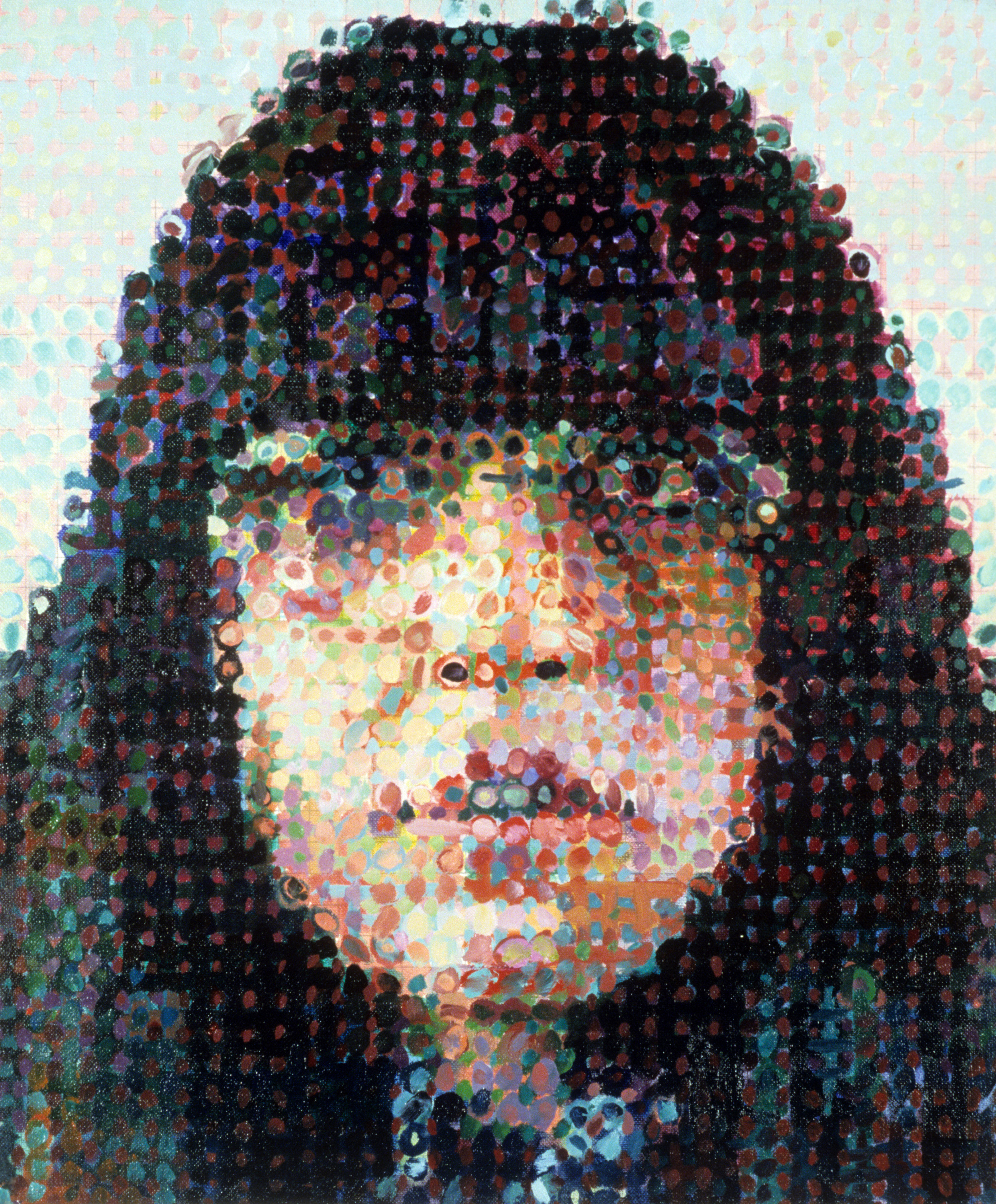

Susan, 1987, Chuck Close. Courtesy of Louis K. Meisel Gallery

Conversely, photorealism has had its own effect on photography. Photographers such as Gursky, Struth, and Eggleston were all influenced by the photorealists of the 1960s and 70s. Meisel believes that since the movement came on the scene, the art world has trended toward representational imagery. “It did bring back imagery and made it the focal point, away from abstract expressionism and back into imagery.” Meisel speculates that Chuck Close may have moved into photorealism in response to his time at Yale, when abstract expressionism was in vogue. Close favored detail over aggressive mark-making, trading his brushes and thick paint for a teaspoon of pigment in an airbrush. Though his work has evolved away from photorealism, Close’s recent daguerreotype portraits have embraced photography completely. His earlier work as a photorealist has undoubtedly influenced his use of the camera.

Like several of Meisel’s artists, Close’s background is in illustration, which shares photography’s struggle for acceptance as a fine art. Meisel acknowledges these two mediums and the influence they have on photorealism. “Everyone knows that the illustrators used photographs, like Norman Rockwell, etcetera, but they weren’t considered ‘real’ artists.” Today photography is unquestionably an art form, but does not yet share the status as other mediums. Meisel exhibits artists who have experience in these genres and mediums, and have incorporated them into their photorealistic work, which is unquestionably considered a fine art.

The gulf between photography and the traditional fine arts is narrowing. Meisel has already made great strides in bridging this gap: In the late 1970s, he produced Photographs of the Photorealists, an exhibition that garnered terrific response. Each artist had ten or so photographs on view in three categories. The first were photographs used to make a painting; some of which had grid marks on them or spots of pigment. The second grouping was photographs made with the intention of making a painting that was never realized. The third category was called Sunday Shots, and was comprised of snapshots from vacations or other informal events with no basis in art-making. The images from the first and second groups were oddly composed close-ups of details, serving as references for paintings. In contrast, the Sunday Shots demonstrated that the artists are skilled photographers in their own right.

The Plaza, Richard Estes. Courtesy of Louis K. Meisel Gallery

For the last 40 years, Meisel has been assembling a movement of painters who reject the notion that painting from photographs cheapens their practice. He dismisses the stigma, believing that, “the camera is a tool and not a crutch.” Rather, their mastery of technology to realize their complex visions and portrayals of the world should be celebrated. Perhaps as photographers, we can learn from this and cease our debates about tools in order to focus on vision and execution, and finding our place amongst the fine arts.

Kat Kiernan is the Editor-in-Chief of Don't Take Pictures.